In the process of getting the non-blocking busy_timeout from the sqlite3 gem used in Rails, I needed to explore the differences between a busy handler implementation that uses a backoff and one that simply polls on a consistent interval. What I found was that a busy handler that backs off kills “tail latency” (how long it takes for the operation in the worst cases). This is because the SQLite “retry queue” behaves very differently from a more traditional queue that we tend to work with and think about, like a background job queue.

When we hear that something has a “retry queue”, we tend to think of the behavior of something like a background job queue. In a typical background job queue, when you say “retry in 1 second”, that job will be executed in 1 second. The “retry” is a command that will be honored. When you can command that a job is retried after a particular interval, you don’t need to worry about “older jobs” (jobs that have been retried more times) having any sort of penalty relative to “newer jobs” and so having some kind of backoff steps makes sense to distribute execution load.

But, with SQLite’s “retry queue”, we aren’t telling SQLite “retry this query in 1 ms” as a command, we are more so saying “you can attempt to run this query again in 1ms”. There is no guarantee that the query will actually run, since it has to attempt to acquire the write lock before running. This slight change in behavior, from retry commands to retry requests, has a big impact on the optimal way to implement a “busy handler” (the code that handles what happens when the operation is can’t be executed because the executor is busy).

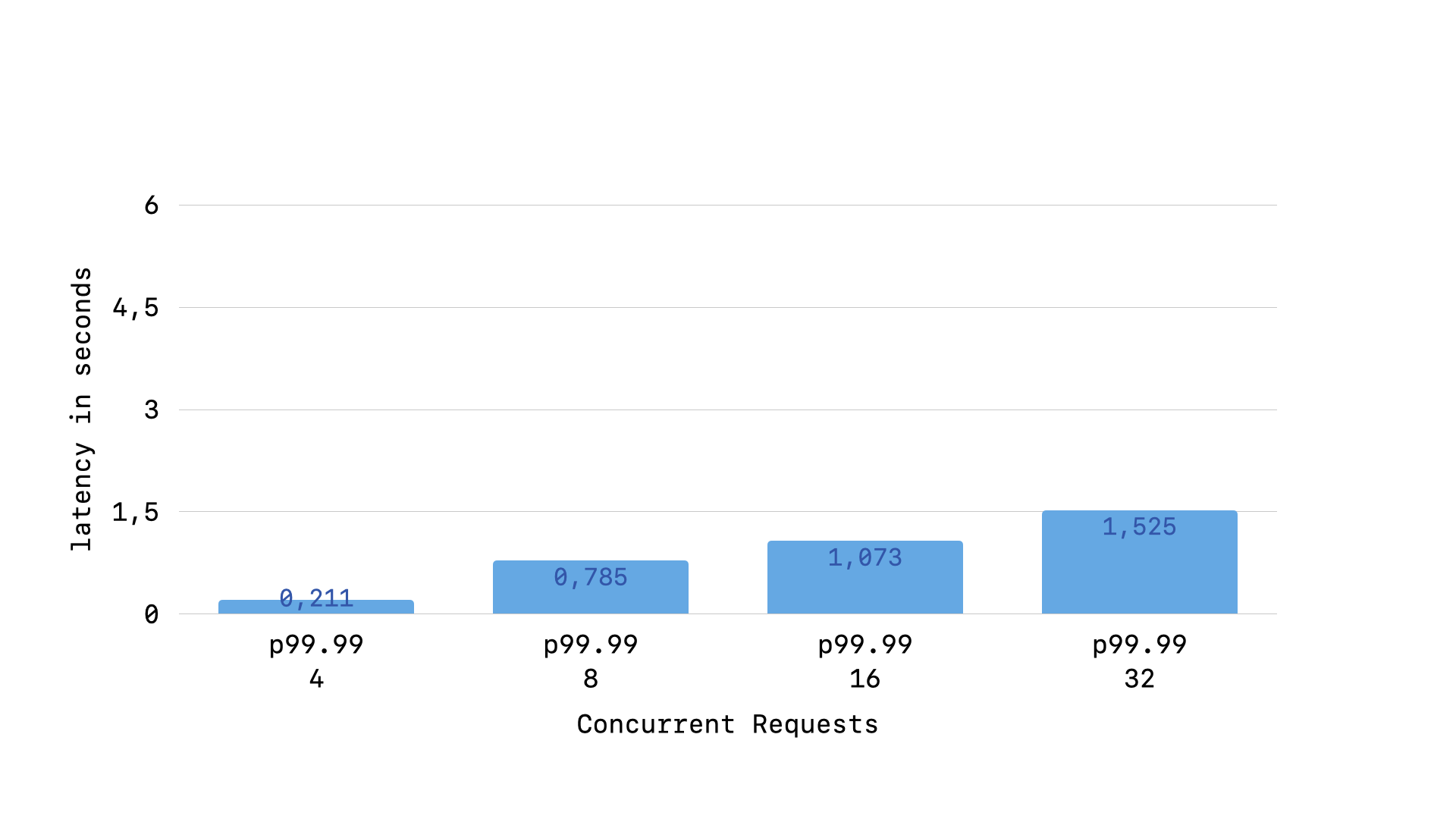

In my in-depth article on optimizing SQLite performance in a Ruby context, I found that having a backoff1 has a noticeable impact on long-tail latency (p99.99 from my load testing):

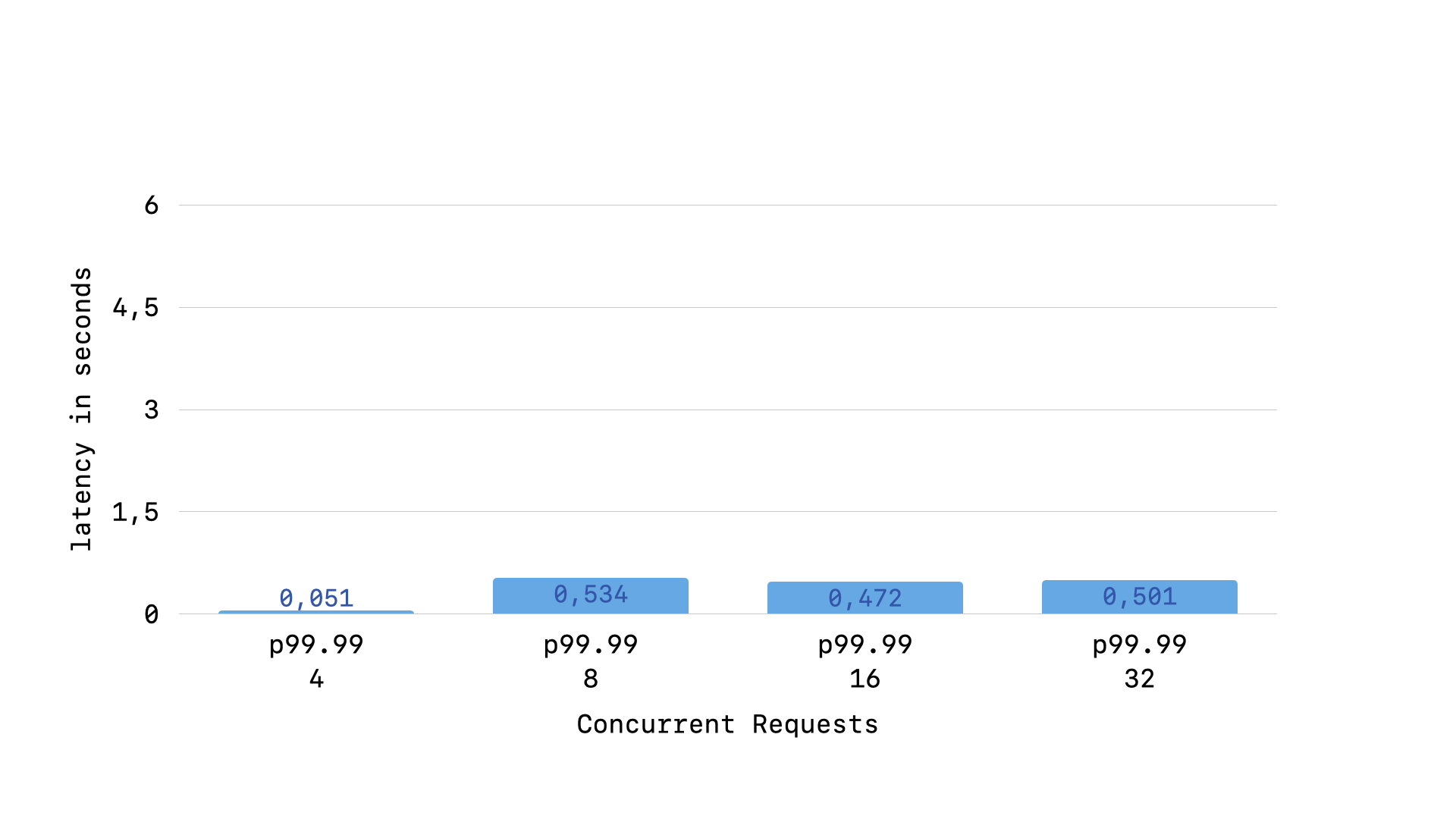

but when using the “fair” retry interval where we always wait the same amount of time regardless of how many times the busy handler has been called, the long-tail latency flattens out:

These early tests show that when you are dealing with a “retry queue” that requests that a query try to run in the future, a backoff penalizes “older queries” (queries that have run the busy handler more times).

But, I wanted to provide a richer collection of data from a wider range of scenarios to ensure that having consistent “retry polling” doesn’t negatively affect the performance of the connection holding the lock.

To consider the impact of polling for the lock, myself and @oldmoe wanted to explore the following three scenarios:

- all queries are fast

- one slow query with contention from fast queries

- two slow queries with contention from fast queries

In order to explore a wide range of situations, we had the contentious fast queries run from a composition of processes and threads. The slow queries were always ran from the single parent process in succession.

You can find the code used to run the various scenarios in this gist

Both modes of the busy_handler ignore any concern of a timeout and simply focus on how to behave when the handler is called. The constant mode will always sleep for 1ms (busy_handler { |_count| sleep 0.001 }) and the backoff mode always sleeps for Nms, where N is the number of times the handler has been called (busy_handler { |count| sleep count * 0.001 }).

We play with 3 variables to create the various contention situations:

- the number of child processes

- the number of threads per child process

- the number of slow queries that the parent process will run

The first situation has the parent process run zero slow queries, so all contention comes from the fast queries that the child connections are running. The ideal case, regardless of the number of child processes and/or threads, is that the script, parent connection, fastest child connection, and slowest child connection all finish in very short durations. This is because the only queries being run inside of the transactions are fast queries (SELECT 1) and so no connection should need to wait very long to acquire the lock. This is what we see with the constant mode, for all variations of this scenario:

MODE | CONTENTION | PARENT | FASTEST | SLOWEST | SCRIPT | DELTA constant | 6 (4/2/0) | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | -3 constant | 8 (4/4/0) | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | -9 constant | 10 (8/2/0) | 0 | 1 | 8 | 3 | -8 constant | 12 (8/4/0) | 0 | 0 | 27 | 3 | -27For the backoff mode, we see the slowest child connection take longer to finish under increased load:

MODE | CONTENTION | PARENT | FASTEST | SLOWEST | SCRIPT | DELTA backoff | 6 (4/2/0) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | -4 backoff | 8 (4/4/0) | 0 | 0 | 26 | 2 | -26 backoff | 10 (8/2/0) | 0 | 0 | 26 | 3 | -26 backoff | 12 (8/4/0) | 0 | 0 | 107 | 3 | -107In the worst case, backoff mode takes 5× longer for the slowest child connection (107ms vs 27ms) than the constant mode.

The second scenario has the parent process run one slow query, so all contention comes from the fast queries that the children connection is running. The ideal case is that the gap between the duration for the parent connection and the script duration is minimal, the gap between the fastest and slowest child connection is minimal. This is because the total script execution time should not be majorly impacted by the child processes (thus the small first gap), the children connections should not have any unfairly punished executions since they are all running only fast queries. These are the results we see for the constant mode in this scenario:

MODE | CONTENTION | PARENT | FASTEST | SLOWEST | SCRIPT | DELTA constant | 7 (4/2/1) | 1071 | 869 | 875 | 1073 | 196 constant | 9 (4/4/1) | 1077 | 876 | 893 | 1078 | 184 constant | 11 (8/2/1) | 1077 | 877 | 891 | 1080 | 186 constant | 13 (8/4/1) | 1076 | 878 | 902 | 1079 | 174What we observe is that the gap between PARENT and SCRIPT does indeed remain miniscule (< 3) and the gap between FASTEST and SLOWEST also remains small (< 33). Yes, there is some small penalty on the parent connection execution time as load increases, but it is not significant (< 7ms for a 1 second query, so 0.7%). The results for the backoff mode do not paint as rosy a picture:

MODE | CONTENTION | PARENT | FASTEST | SLOWEST | SCRIPT | DELTA backoff | 7 (4/2/1) | 1064 | 878 | 942 | 1066 | 122 backoff | 9 (4/4/1) | 1069 | 868 | 1018 | 1071 | 51 backoff | 11 (8/2/1) | 1071 | 875 | 1173 | 1074 | -102 backoff | 13 (8/4/1) | 1066 | 873 | 1424 | 1069 | -358While the gap between PARENT and SCRIPT stays small (< 8), the gap between FASTEST and SLOWEST grows significantly (< 551). The slowest child connection takes 2.5× longer to finish in the worst case than the best case. This is on top of the fact that the lag on the parent connection execution time is identical (7ms).

In the third scenario, where the parent connection is running two slow queries with 1ms gap in between executions, we hope to see that the fast child queries are able to acquire the lock between the two slow queries running in the parent. We then similarly want to see that the gap between fastest and slowest child connections is minimal (tho it will be larger than previous scenarios, because the slowest child connection will be the one that has to wait for both slow parent queries to finish). Here are the results for the constant mode:

MODE | CONTENTION | PARENT | FASTEST | SLOWEST | SCRIPT | DELTA constant | 8 (4/2/2) | 2142 | 871 | 1944 | 2144 | 198 constant | 10 (4/4/2) | 2144 | 871 | 1952 | 2146 | 192 constant | 12 (8/2/2) | 2141 | 867 | 1953 | 2143 | 188 constant | 14 (8/4/2) | 2163 | 883 | 1984 | 2166 | 179We see that indeed the fastest child connections remain fast, while the slowest child connections are only slightly faster than the parent connection (the 200ms that we have the child processes sleep before beginning). For the backoff mode, the fastest queries are noticably slower, and the slowest queries get progressively slower under increasing contention:

MODE | CONTENTION | PARENT | FASTEST | SLOWEST | SCRIPT | DELTA backoff | 8 (4/2/2) | 2127 | 1926 | 2044 | 2129 | 83 backoff | 10 (4/4/2) | 2132 | 1998 | 2204 | 2134 | -72 backoff | 12 (8/2/2) | 2143 | 1952 | 2324 | 2145 | -181 backoff | 14 (8/4/2) | 2133 | 1992 | 2475 | 2135 | -342So, I believe it is fair to say that across all three situations, the constant mode (i.e. the “fair” busy handler with no backoff) is superior to the backoff mode.

If you want, you can view all of the raw results in the full output file

Up next, taking this “scenario engine” and exploring what busy_handler implementations are optimal across the various scenarios to see if we can improve the implementation currently in the sqlite3 gem. While the current implementation with consistent polling is certainly better than the backoff, we may be able to improve even further with some small tweaks. Exploration ahead!

-

in my testing I used SQLite’s backoff:

delays = [1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 25, 25, 50, 50, 100]↩