Over the last year or so, I have found myself on a journey to deeply understand how to run Rails applications backed by SQLite performantly and resiliently. In that time, I have learned various lessons that I want to share with you all now. I want to walk through where the problems lie, why they exist, and how to resolve them.

And to start, we have to start with the reality that…

Unfortunately, running SQLite on Rails out-of-the-box isn’t viable today. But, with a bit of tweaking and fine-tuning, you can ship a very performant, resilient Rails application with SQLite. And my personal goal for Rails 8 is to make the out-of-the-box experience fully production-ready.

And so, I have spent the last year digging into the details to uncover what the issues are with SQLite on Rails applications as they exist today and how to resolve those issues. So, let me show you everything you need to build a production-ready SQLite-driven Rails application today…

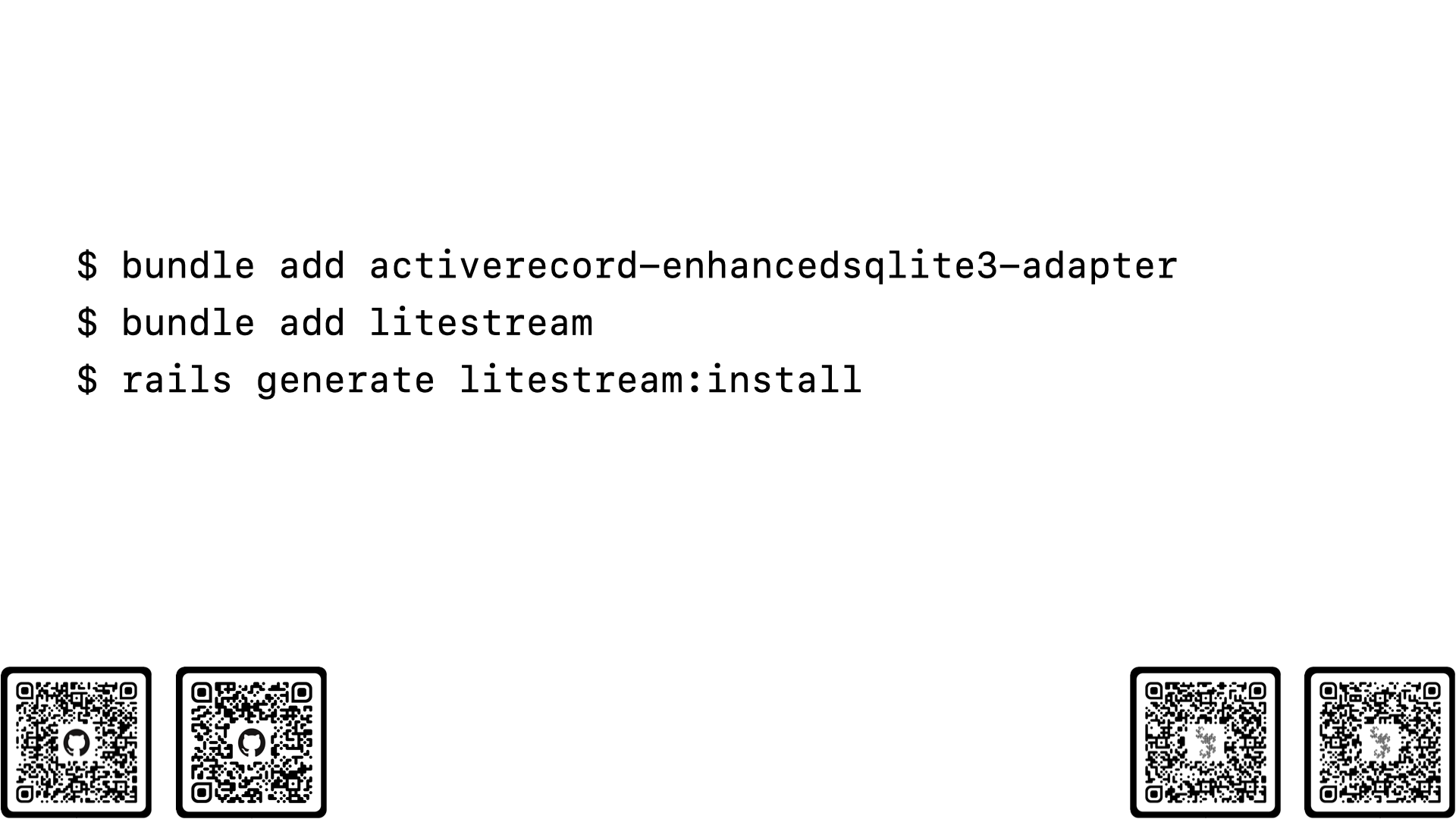

… Yeah, not too bad, huh? These three commands will set your app up for production success. You will get massive performance improvements, additional SQL features, and point-in-time backups. This is how you build a production-ready SQLite on Rails application today.

… And that’s all you need. Thank you. And I could genuinely stop the talk here. You know how and why to run SQLite in production with Rails. Those two gems truly are the headline, and if you take-away only 1 thing from this talk, let it be that slide.

But, given that this is a space for diving deep into complex topics, I want to walk through the exact problems and solutions that these gems package up.

To keep this journey practical and concrete, we will be working on a demo app called “Lorem News”. It is a basic Hacker News clone with posts and comments made by users but all of the content is Lorem Ipsum. This codebase will be the foundation for all of our examples and benchmarks.

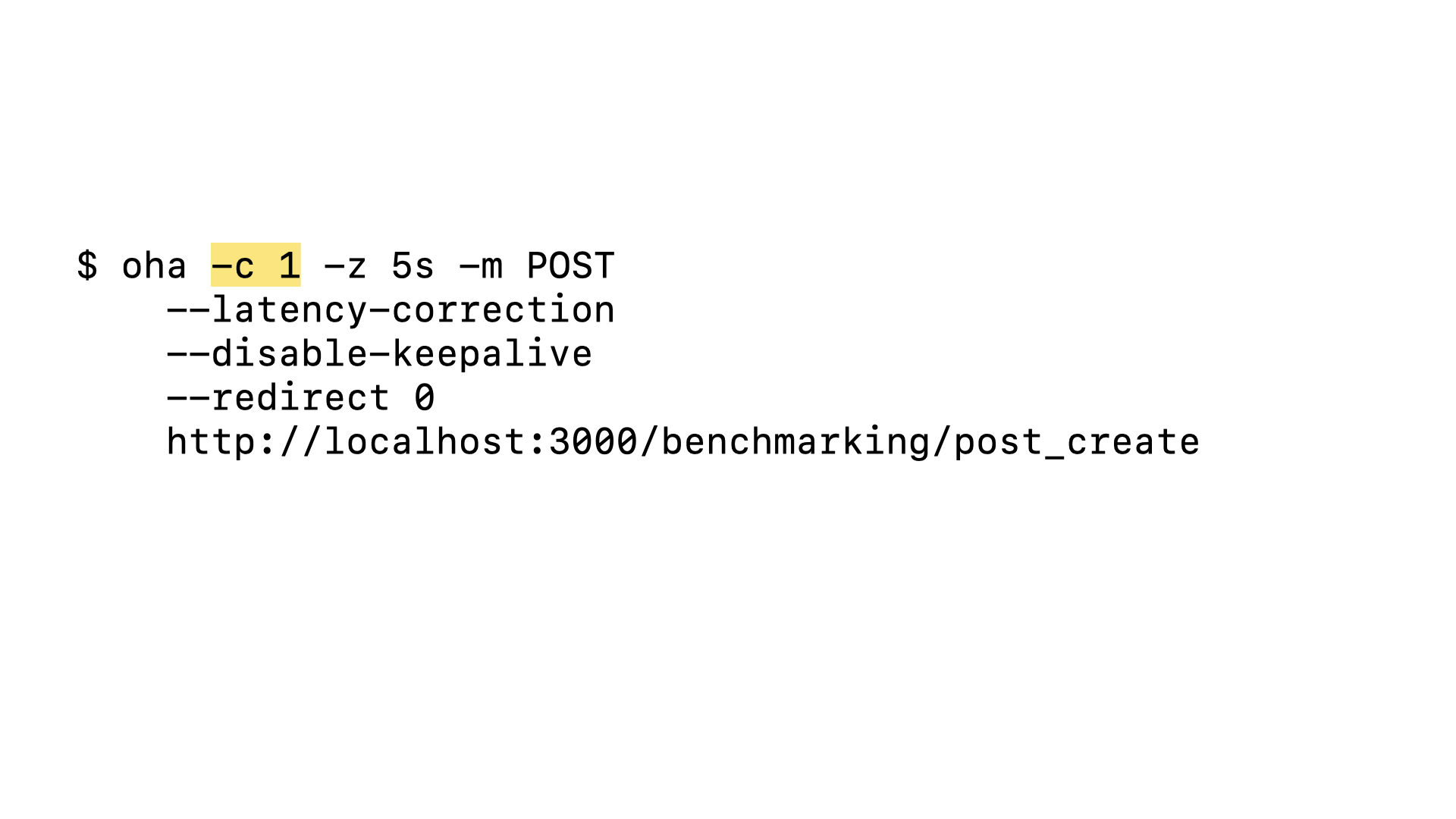

Let’s observe how our demo application performs. We can use the oha load testing CLI and the benchmarking routes built into the app to simulate user activity in our app. Let’s start with a simple test where we sent 1 request after another for 5 seconds to our post#create endpoint.

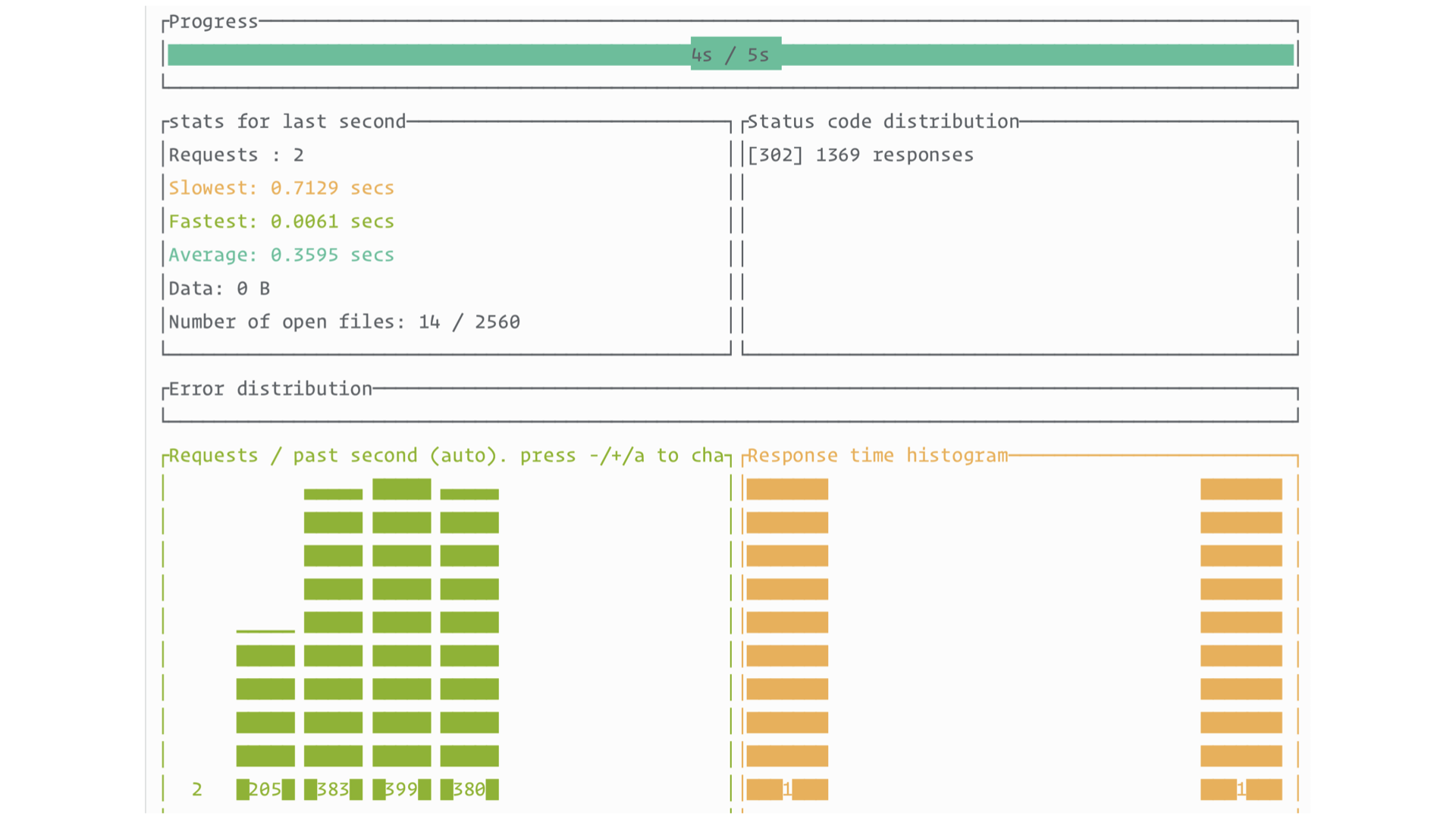

Not bad. We see solid RPS and every request is successful. The slowest request is many times slower than the average, which isn’t great, but even that request isn’t above 1 second. I’ve certainly seen worse. Maybe I was wrong to say that the out-of-the-box experience with Rails and SQLite isn’t production-ready as of today.

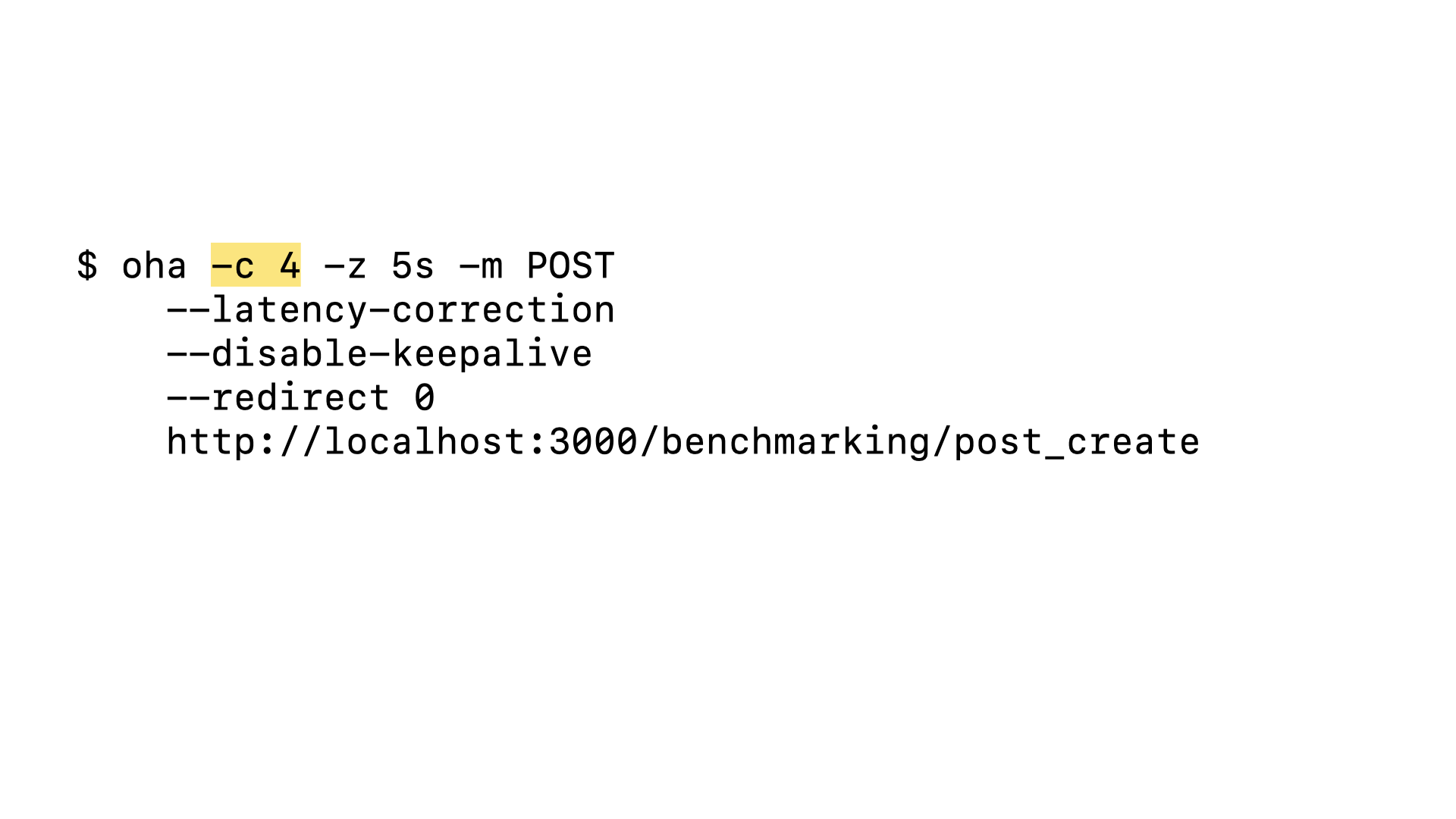

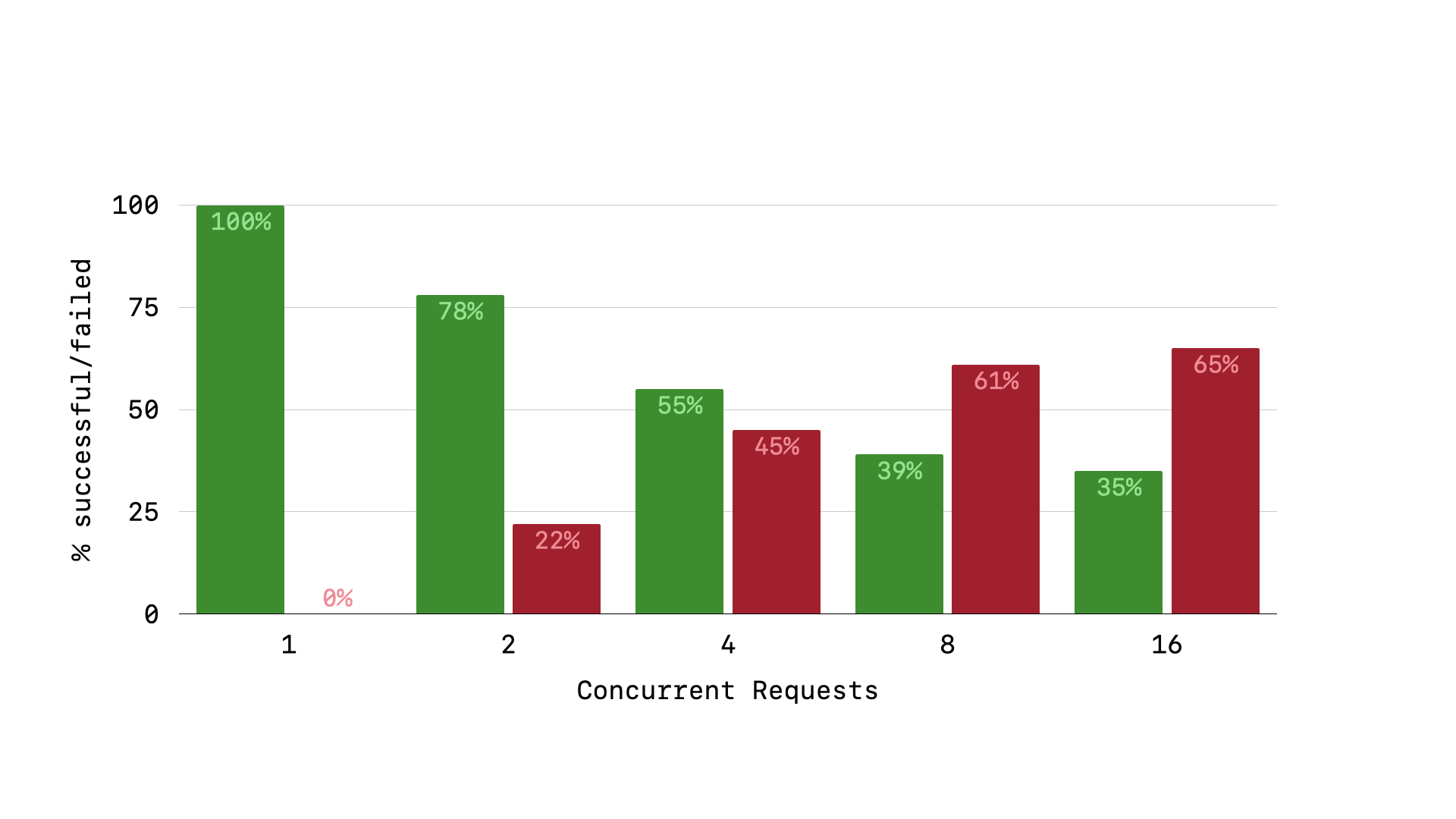

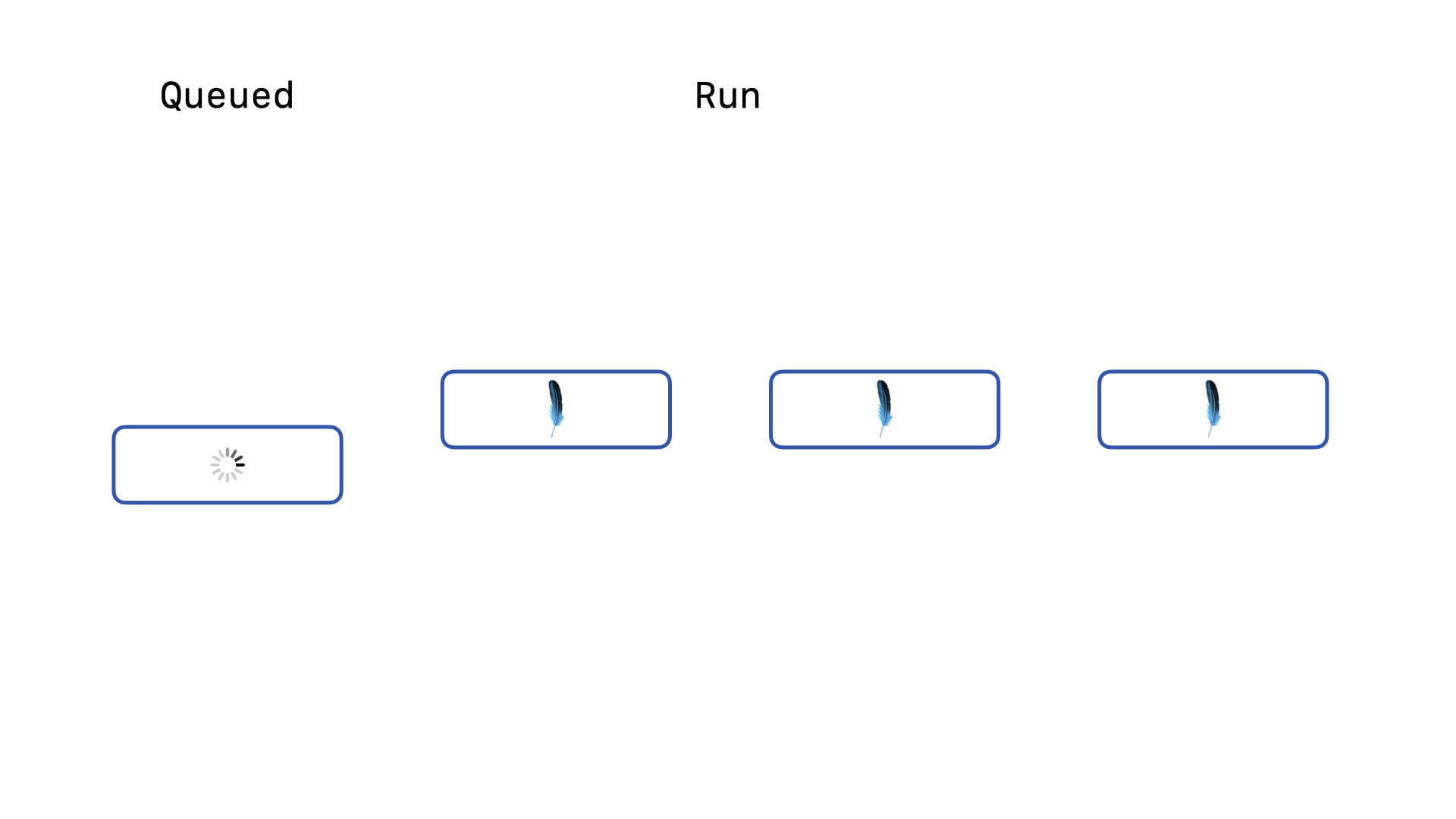

Let’s try the same load test but send 4 concurrent requests in waves for 5 seconds.

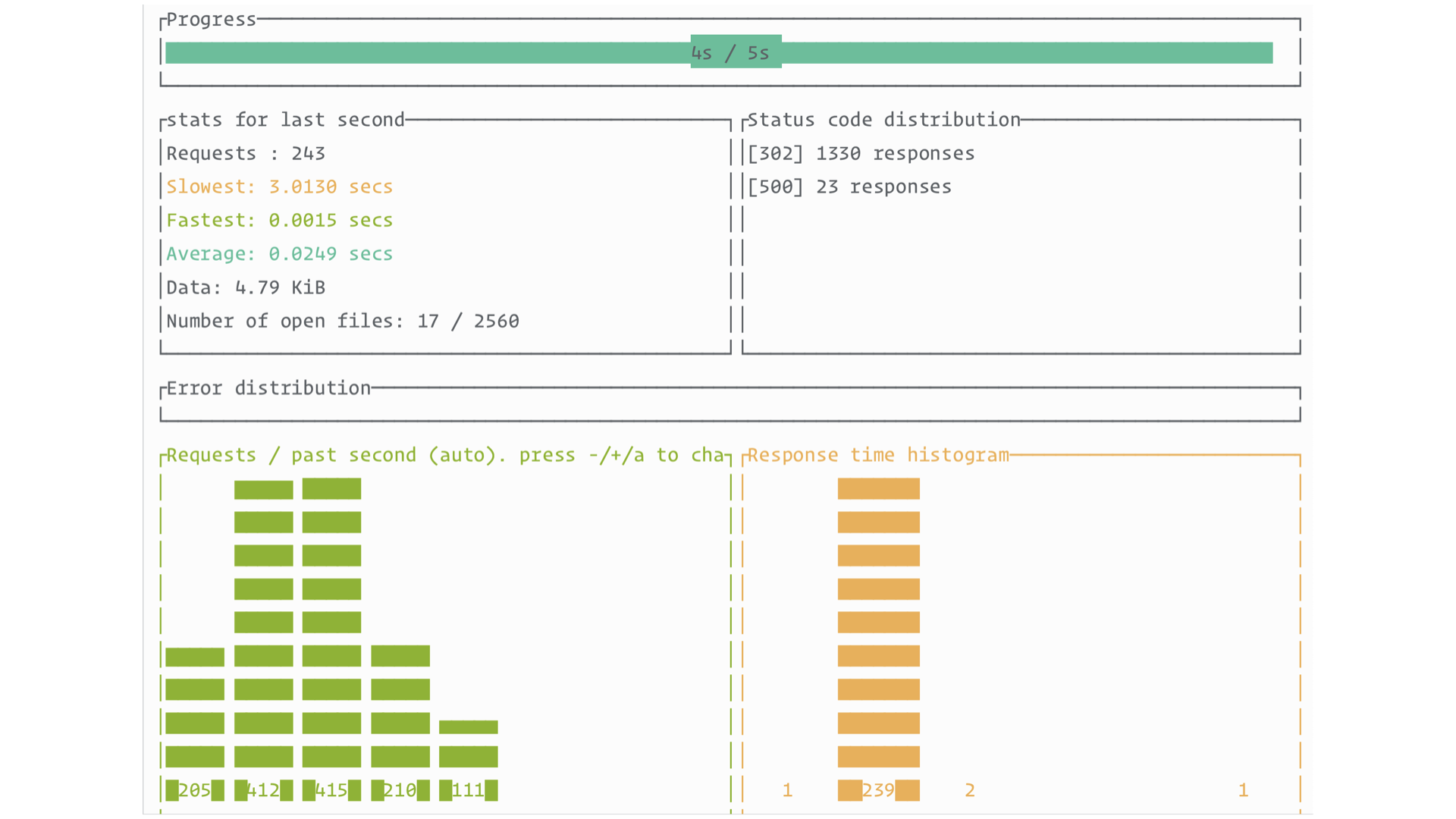

All of a sudden things aren’t looking as good any more. We see a percentage of our requests are returning 500 error code responses.

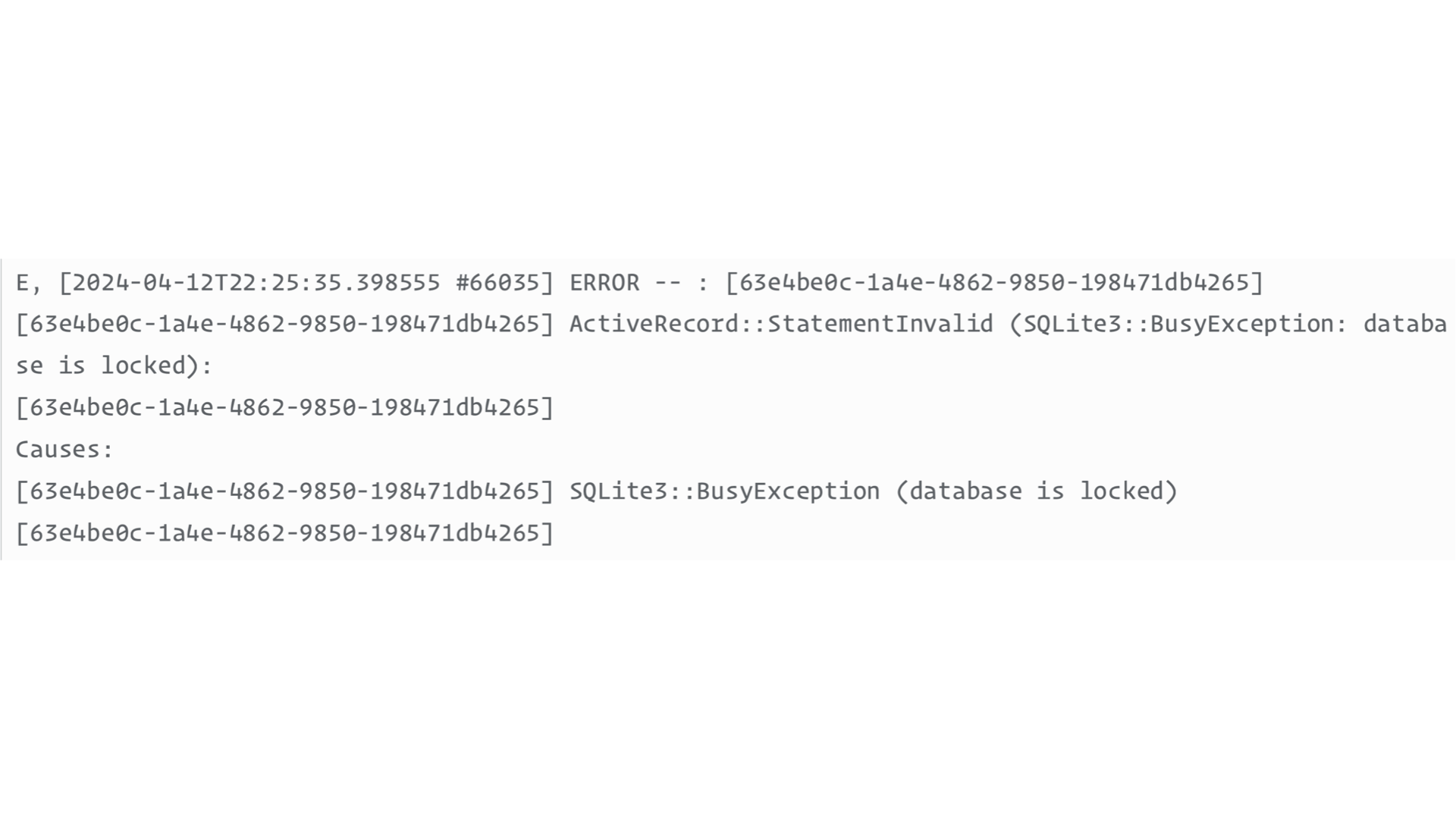

If we look at our logs, we will see the first major problem that SQLite on Rails applications need to tackle …

… the SQLITE_BUSY exception.

In order to ensure only one write operation occurs at a time, SQLite uses a write lock on the database. Only one connection can hold the write lock at a time. If you have multiple connections open to the database, this is the exception that is thrown when one connection attempts to acquire the write lock but another connection still holds it. Without any configuration, a web app with a connection pool to a SQLite database will have numerous errors in trying to respond to requests.

As your Rails application is put under more and more concurrent load, you will see a steady increase in the percentage of requests that error with the SQLITE_BUSY exception. What we need is a way to allow write queries to queue up and resolve linearly without immediately throwing an exception.

Enter immediate transactions. Because of the global write lock, SQLite needs different transaction modes for different possible behaviors.

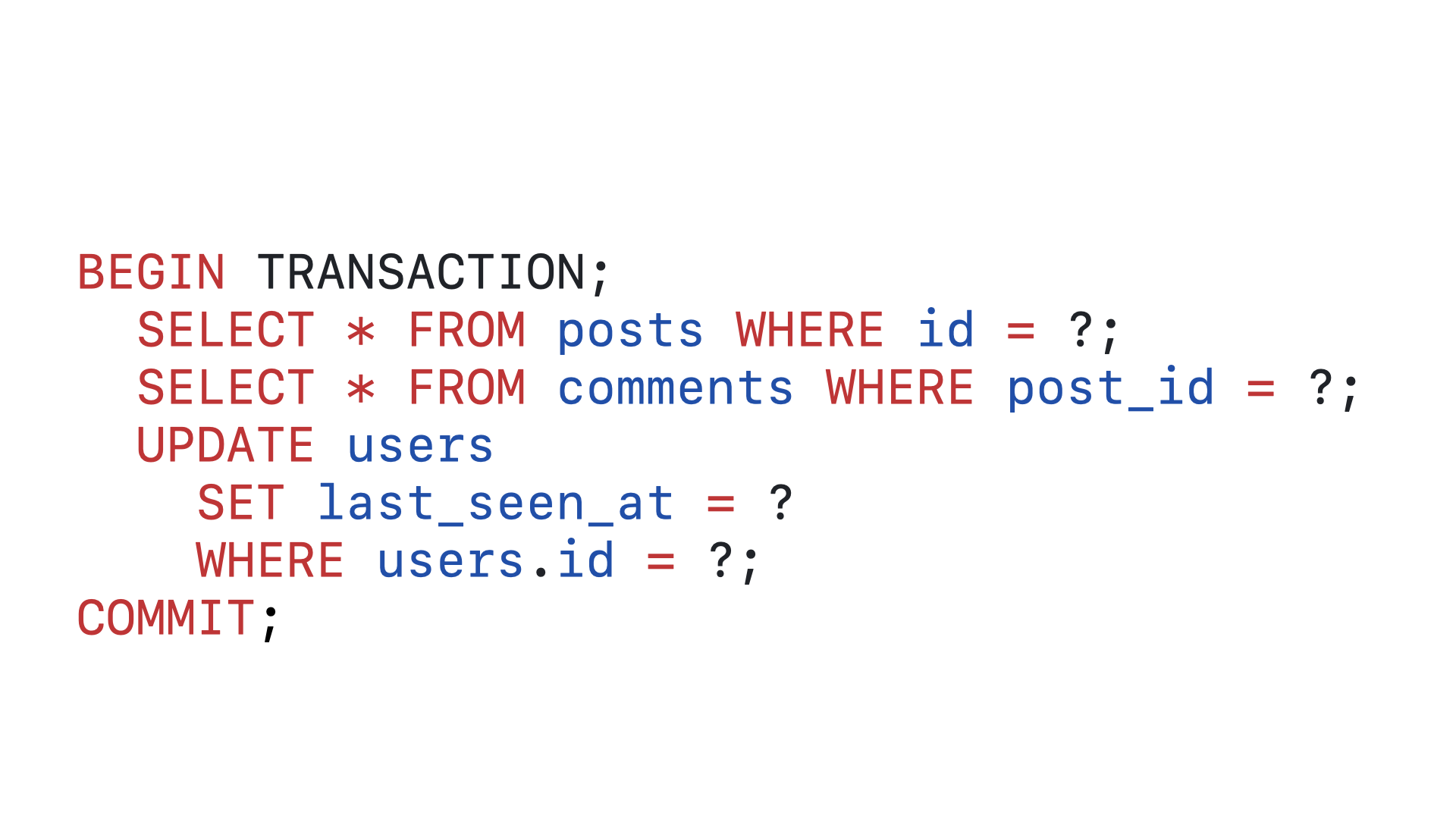

Let’s consider this transaction.

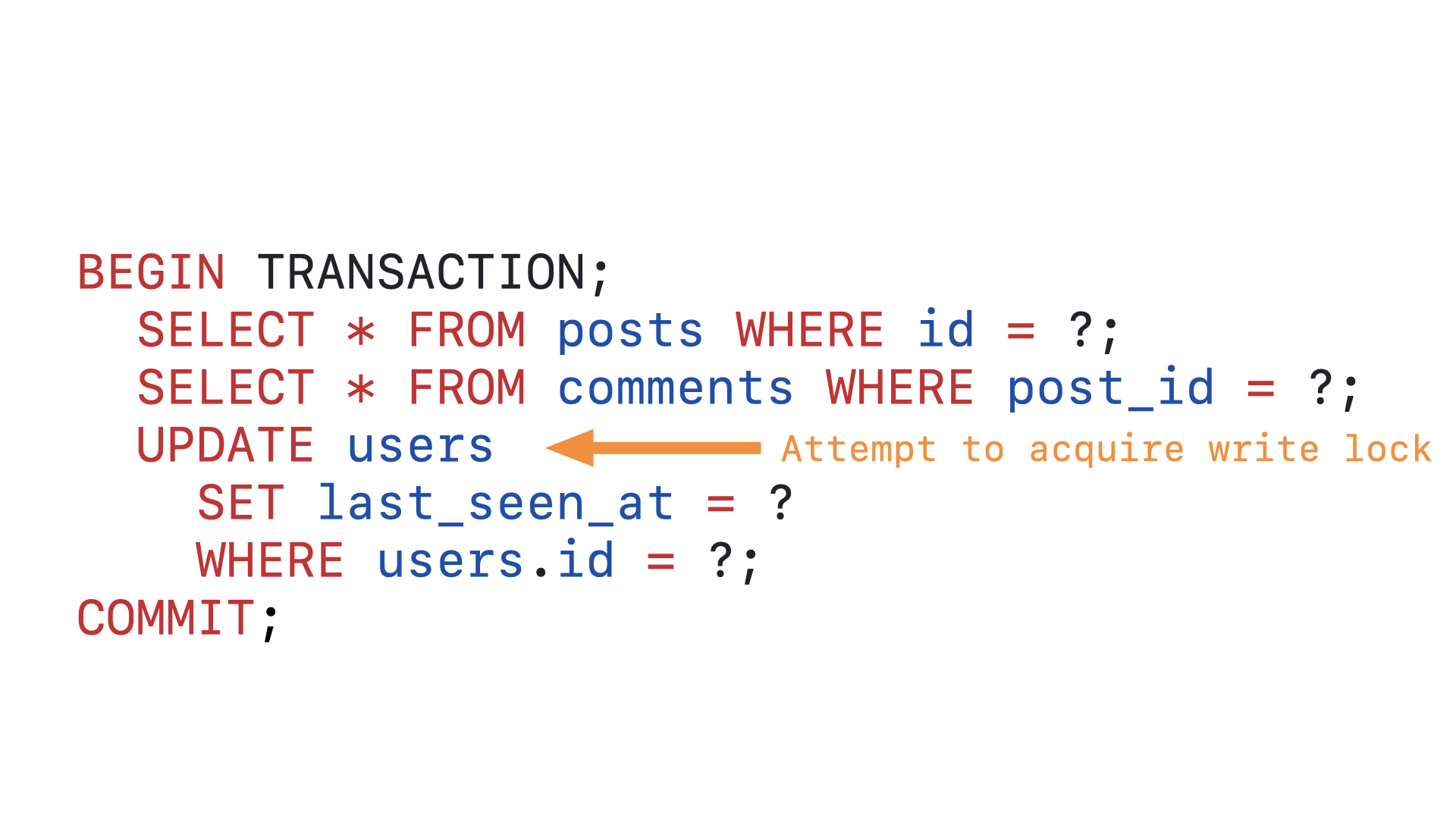

By default, SQLite uses a deferred transaction mode. This means that SQLite will not acquire the lock until a write operation is made inside the transaction. For this transaction, this means that the write lock won’t attempt to be acquired until …

… this line here, the third operation within the transaction.

In a context where you only have one connection or you have a large amount of transactions that only do read operations, this is great for performance, because it means that SQLite doesn’t have to acquire a lock on the database for every transaction, only for transactions that actually write to the database. The problem is that this is not the context Rails apps are in.

In a production Rails application, not only will you have multiple connections to the database from multiple threads, Rails will only wrap database queries that write to the database in a transaction. And, when we write our own explicit transactions, it is essentially a guarantee that we will include a write operation. So, in a production Rails application, SQLite will be working with multiple connections and every transaction will include a write operation. This is the opposite of the context that SQLite’s default deferred transaction mode is optimized for.

Our SQLITE_BUSY exceptions are arising from the fact that when SQLite attempts to acquire the write lock in the middle of a transaction and there is another connection holding the lock, SQLite cannot safely retry that transaction-bound query. Retrying in the middle of a transaction could break the serializable isolation that SQLite guarantees. Thus, when SQLite hits a busy exception when trying to upgrade a transaction, it can’t queue that query to retry acquiring the write lock later; it immediately throws the error and halts that transaction.

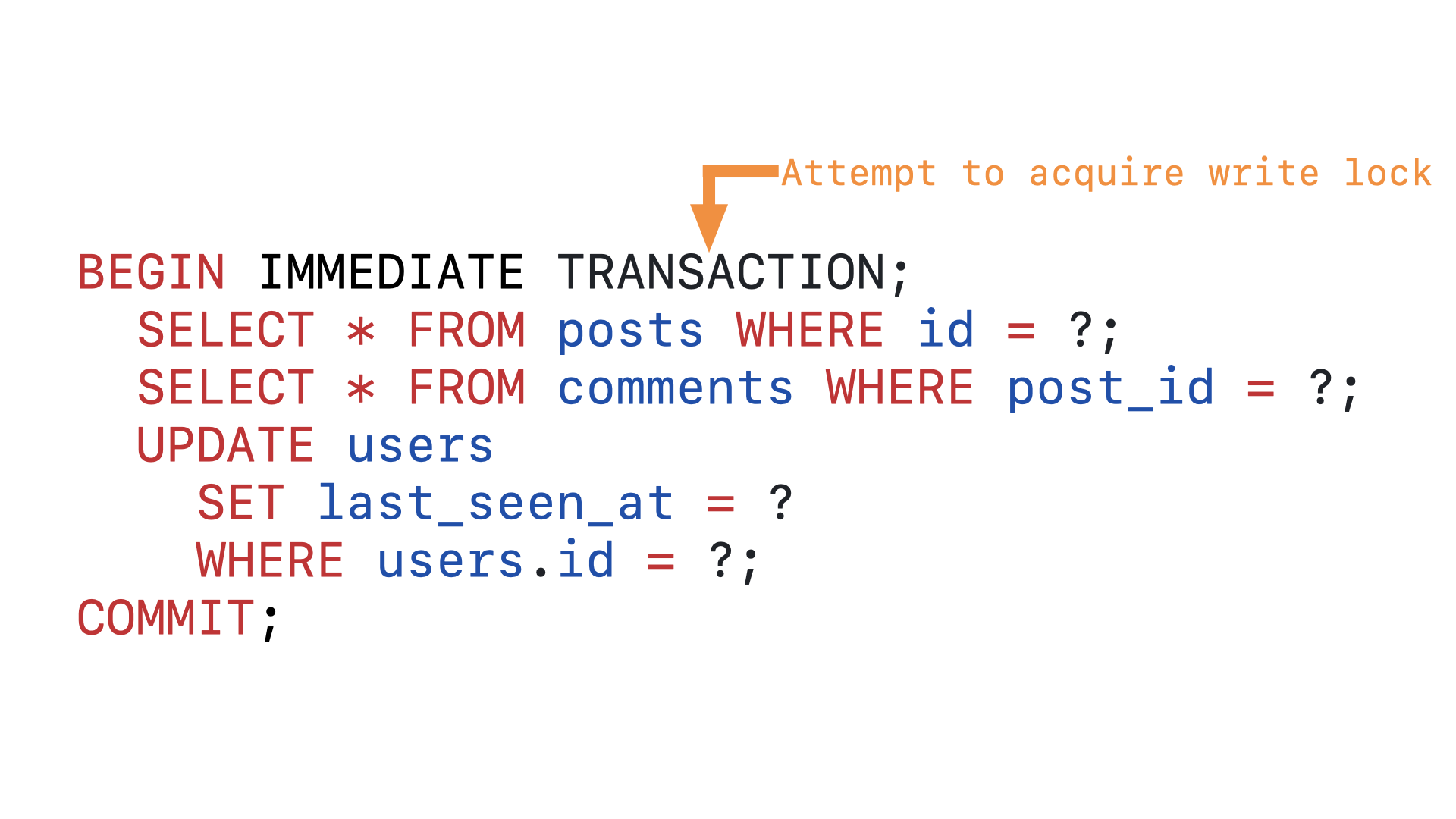

If we instead begin the transaction by explicitly declaring this an immediate transaction, SQLite will be able to queue this query to retry acquiring the write lock again later. This gives SQLite the ability to serialize the concurrent queries coming in by relying on a basic queuing system, even when some of those queries are wrapped in transactions.

So, how do we ensure that our Rails application makes all transactions immediate? …

… As of version 1.6.9, the sqlite3-ruby gem allows you to configure the default transaction mode. Since Rails passes any top-level keys in your database.yml configuration directly to the sqlite3-ruby database initializer, you can easily ensure that Rails’ SQLite transactions are all run in IMMEDIATE mode.

Let’s make this change in our demo app and re-run our simple load test.

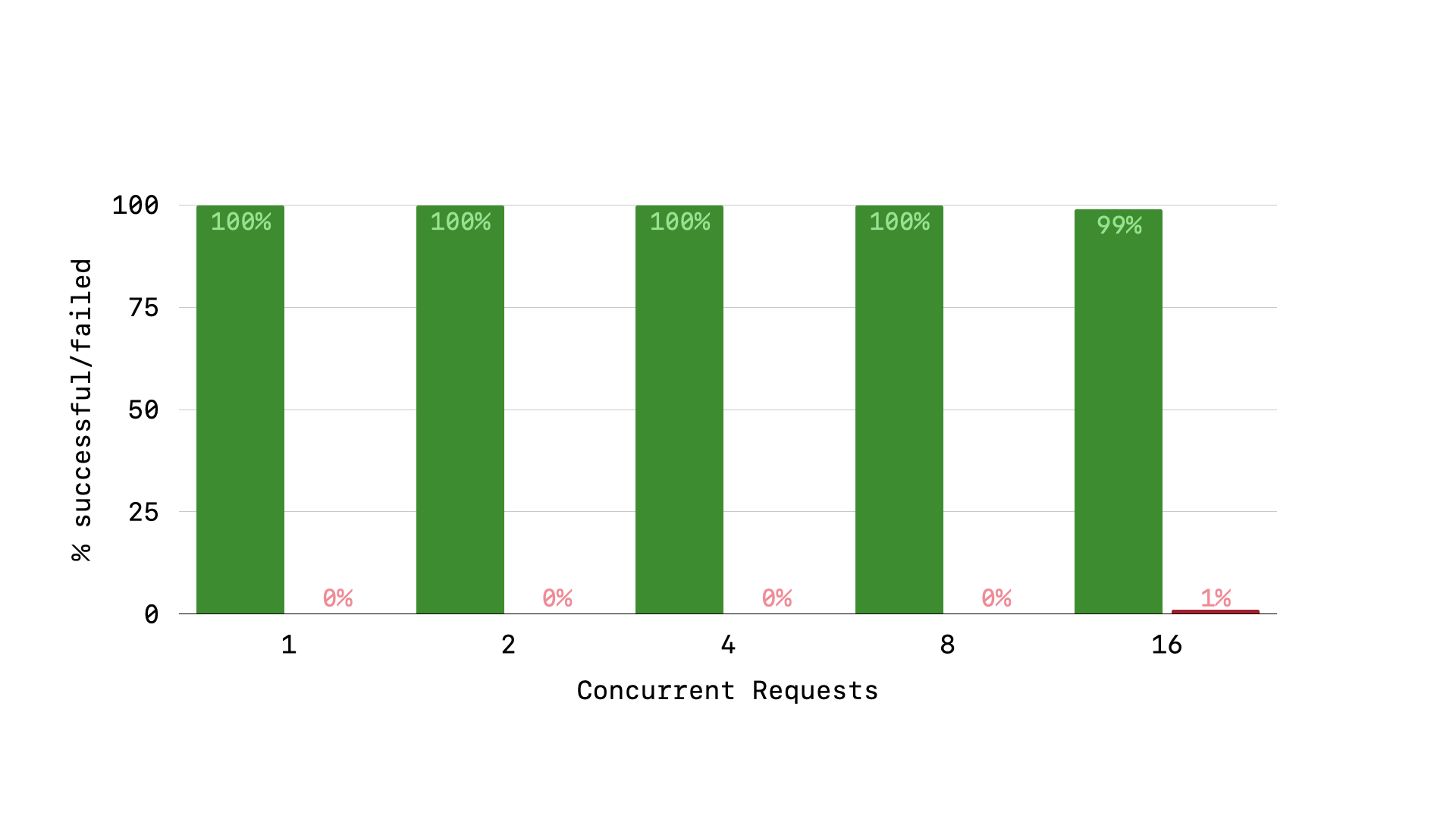

With one simple configuration change, our Rails app now handle concurrent load without throwing nearly any 500 errors! Though we do see some errors start to creep in at 16 concurrent requests. This is a signal that something is still amiss.

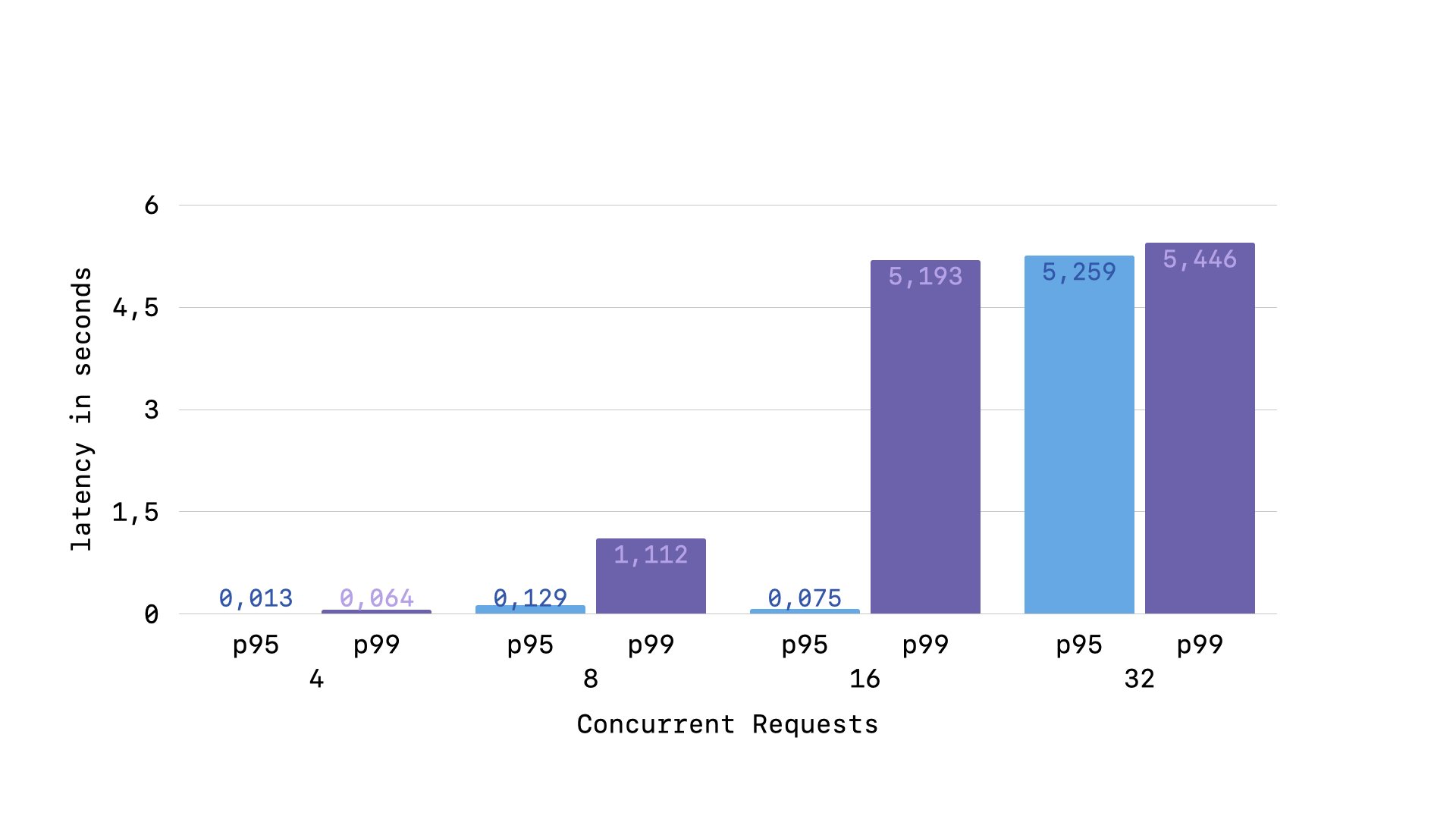

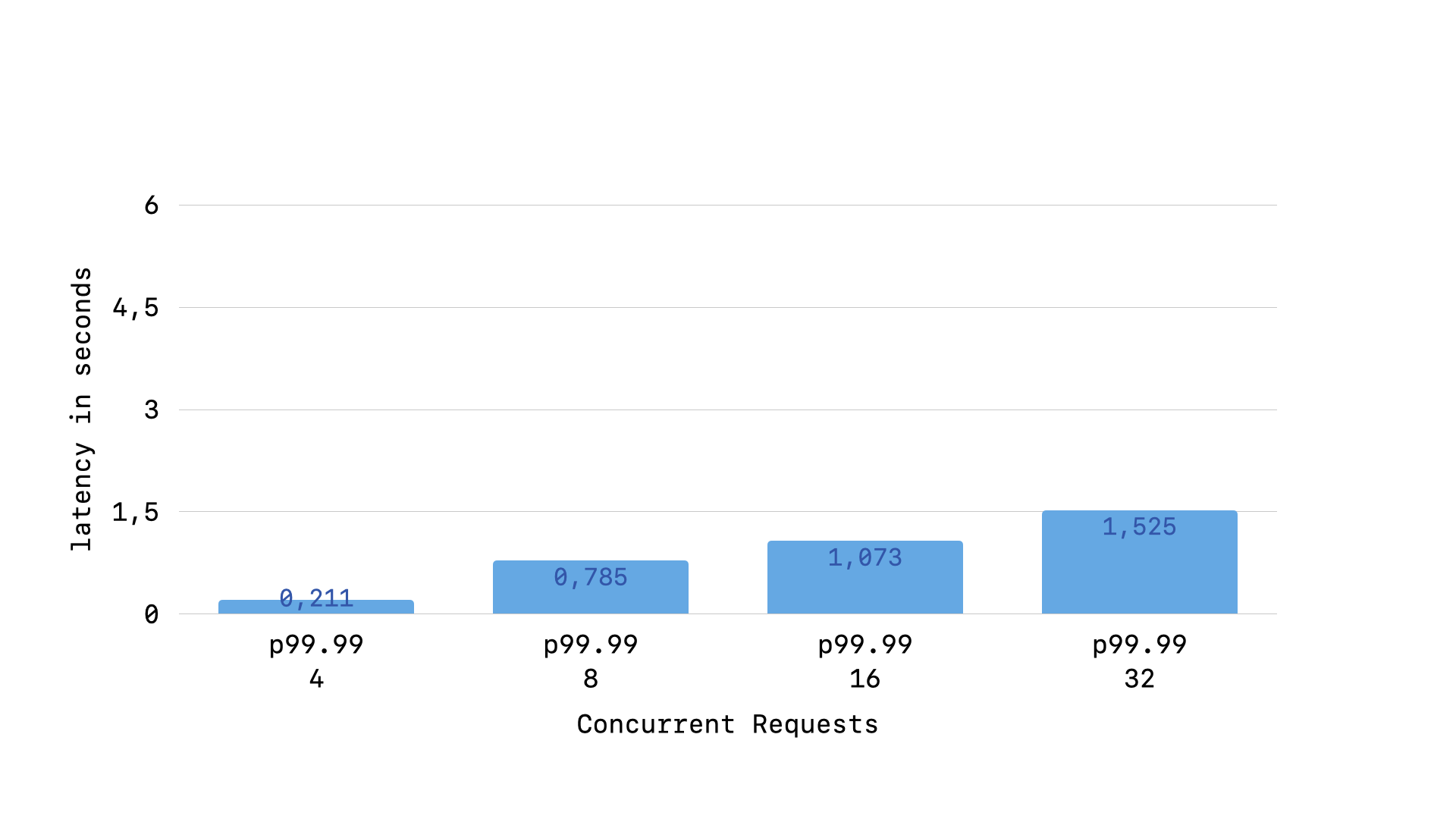

If we look now at the latency results from our load tests, we will see that this new problem quickly jumps out.

As the number of concurrent requests approaches and then surpasses the number of Puma workers our application has, our p99 latency skyrockets. But, interestingly, the actual request time stays stable, even under 3 times the concurrent load of our Puma workers. We will also see that once we start getting some requests taking approximately 5 seconds, we also start getting some 500 SQLITE_BUSY responses as well.

If that 5 seconds is ringing a bell, it is because that is precisely what our timeout is set to. It seems that as our application is put under more concurrent load than the number of Puma workers it has, more and more database queries are timing out. This is our next problem to solve.

This timeout option in our database.yml configuration file will be mapped to one of SQLite’s configuration pragmas…

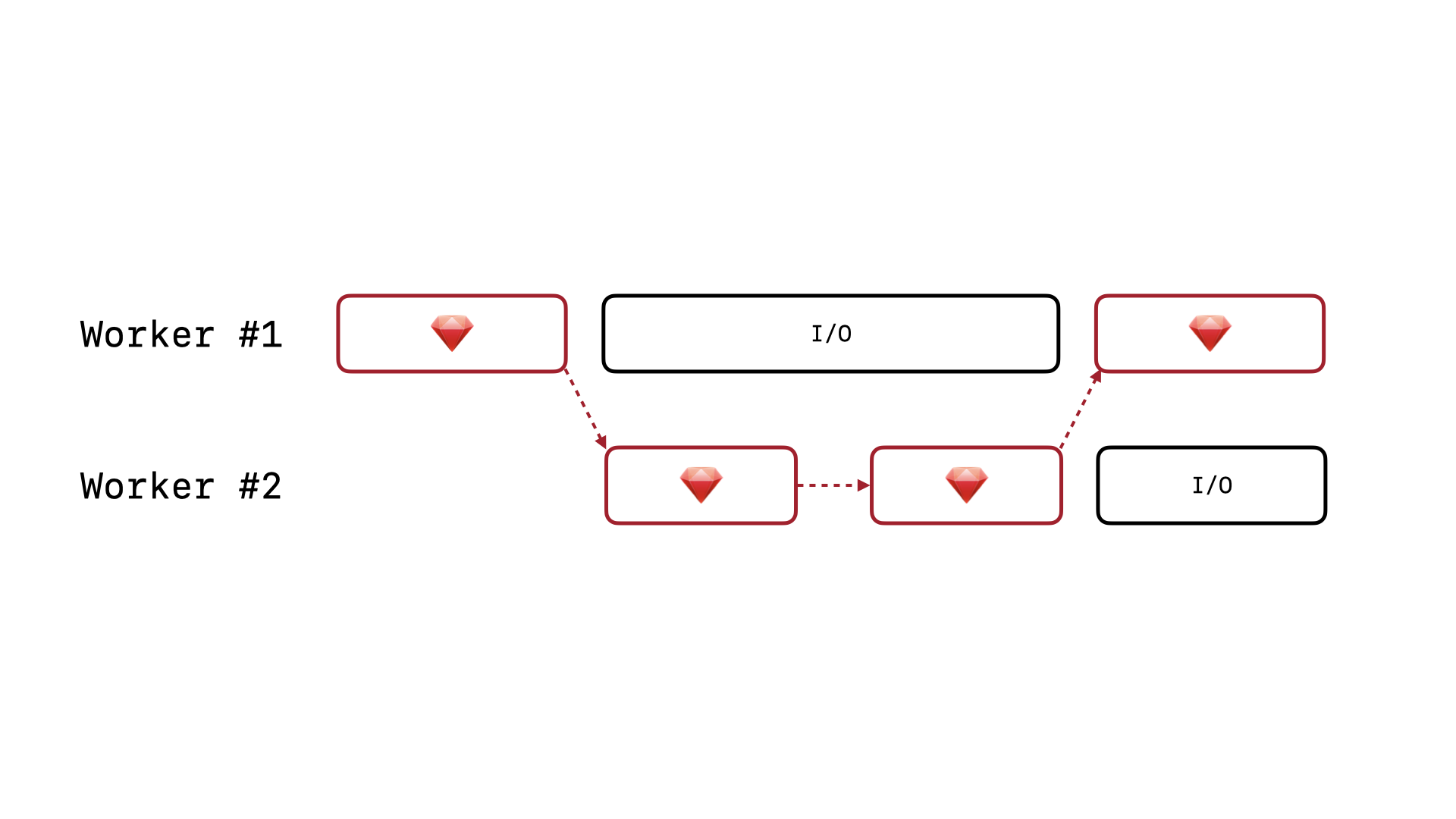

SQLite’s busy_timeout configuration option. Instead of throwing the BUSY exception immediately, you can tell SQLite to wait up to the timeout number of milliseconds. SQLite will attempt to re-acquire the write lock using a kind of exponential backoff, and if it cannot acquire the write lock within the timeout window, then and only then will the BUSY exception be thrown. This allows a web application to use a connection pool, with multiple connections open to the database, but not need to resolve the order of write operations itself. You can simply push queries to SQLite and allow SQLite to determine the linear order that write operations will occur in. The process will look something like this:

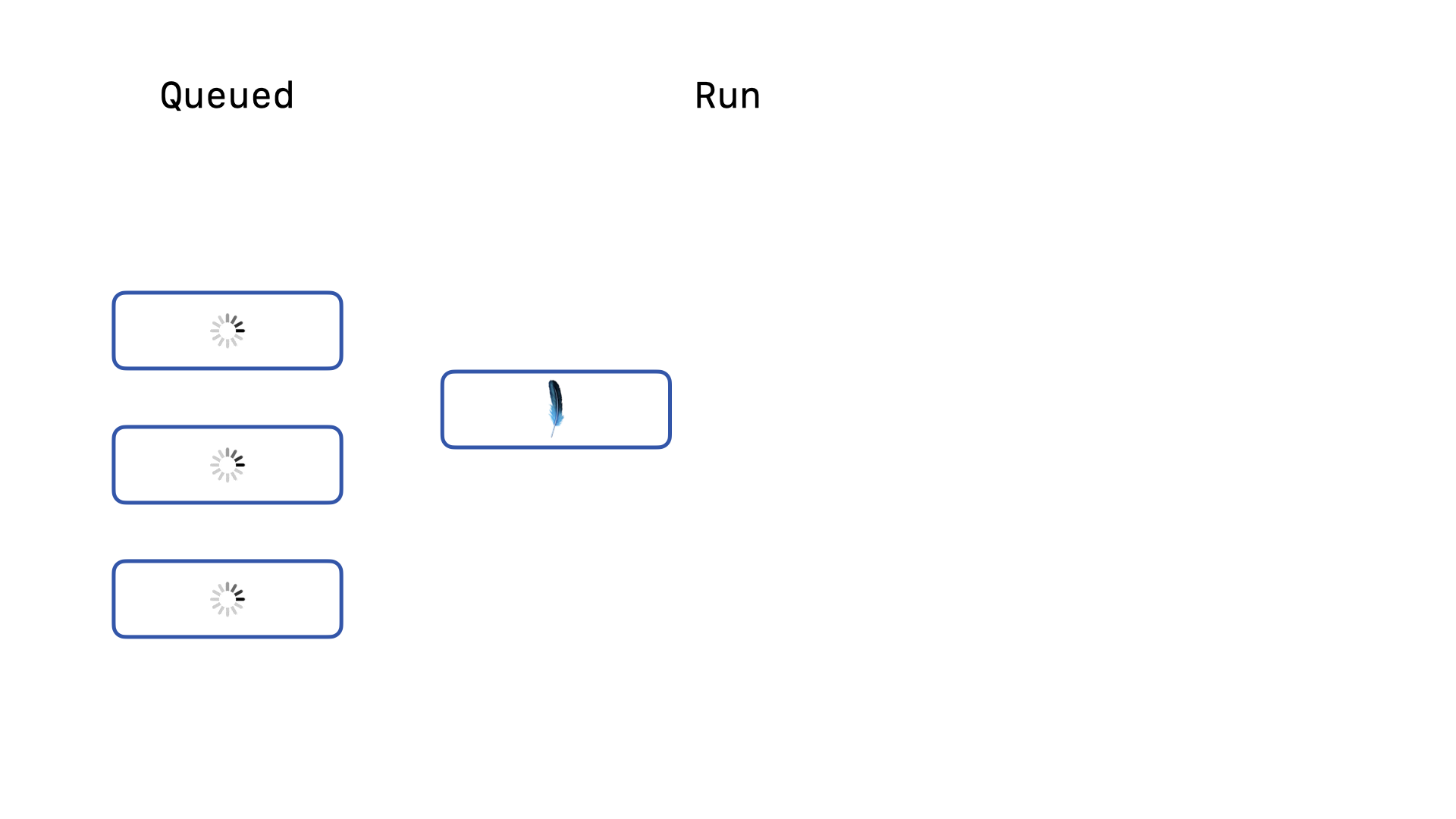

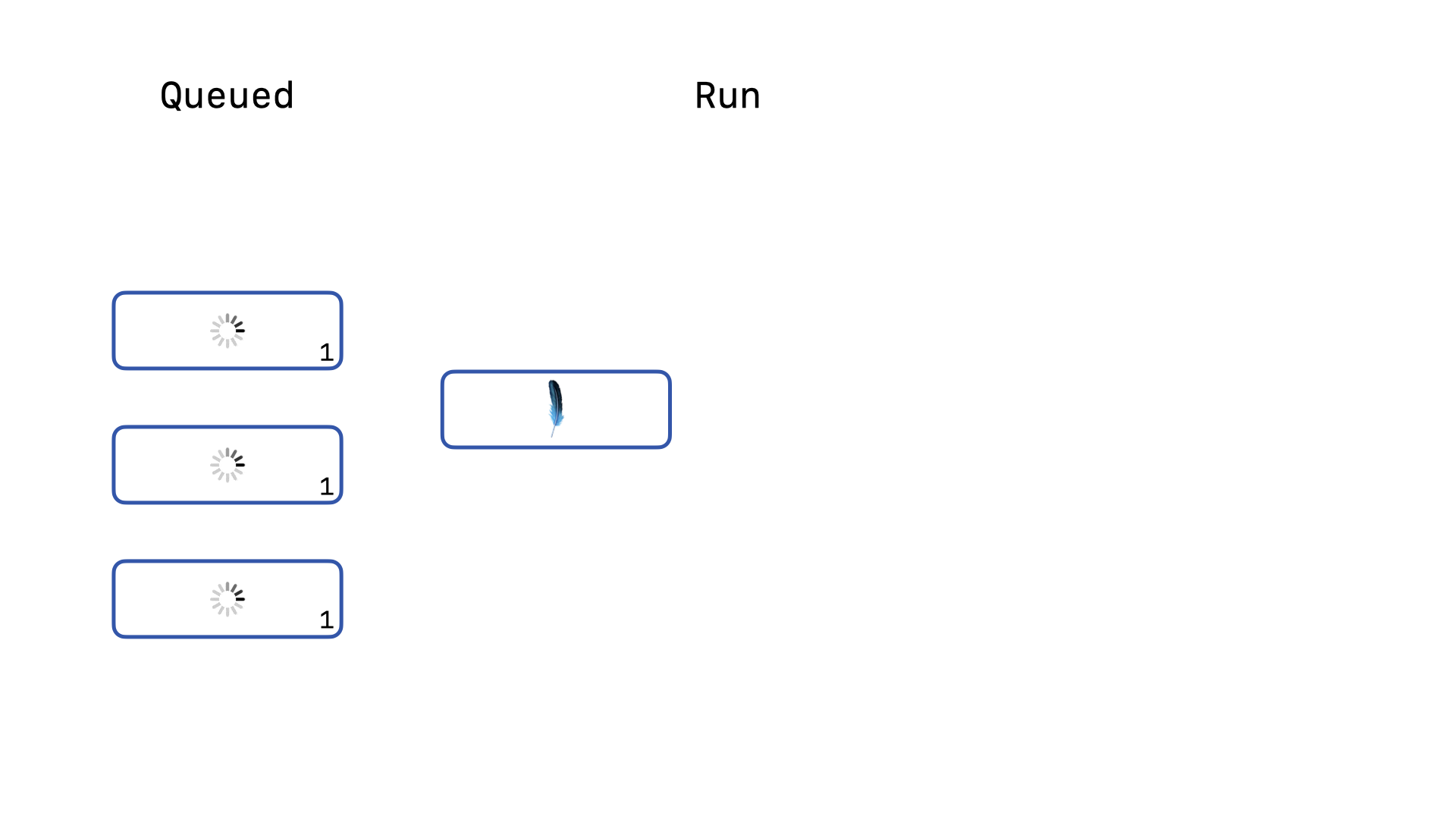

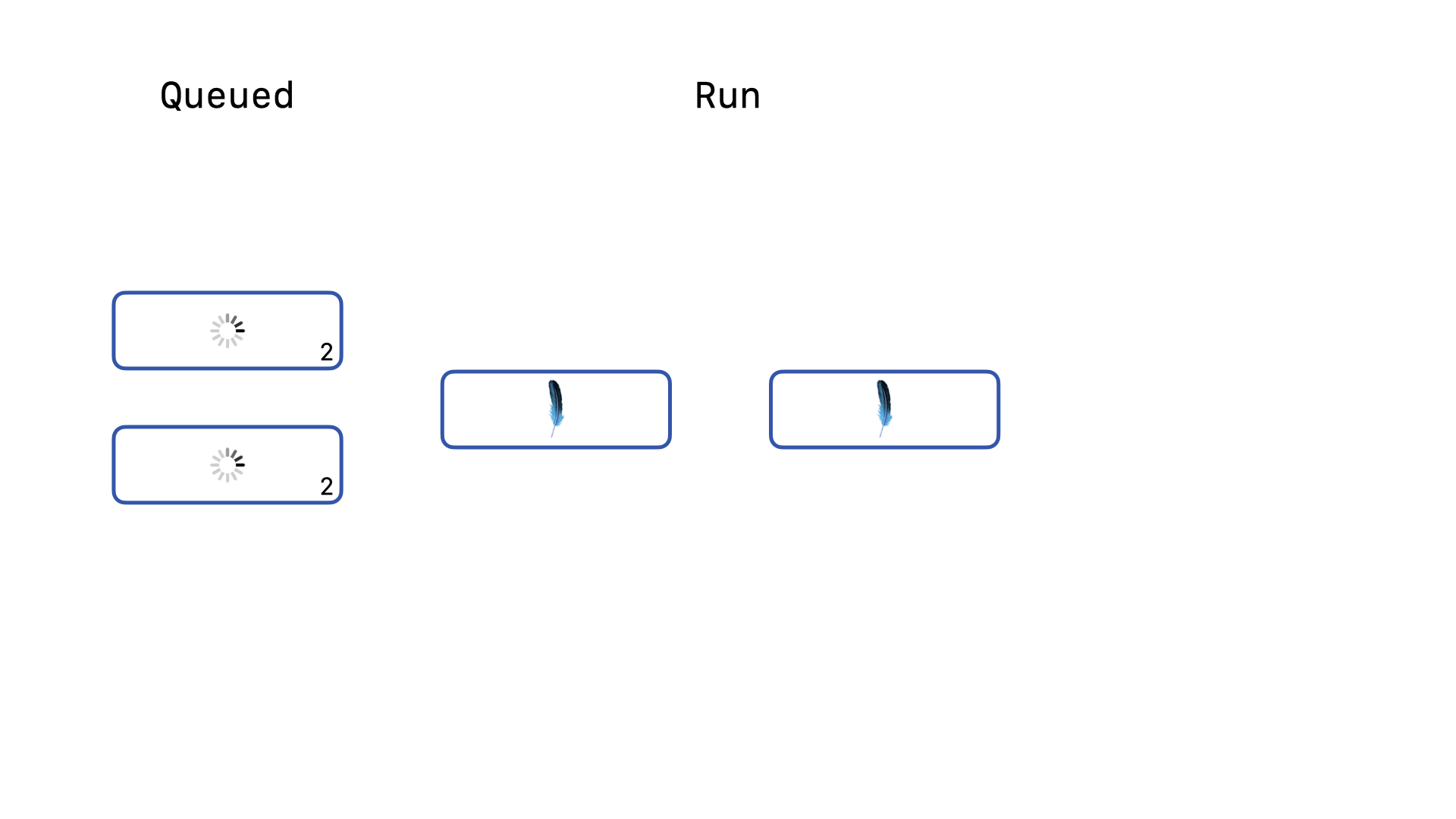

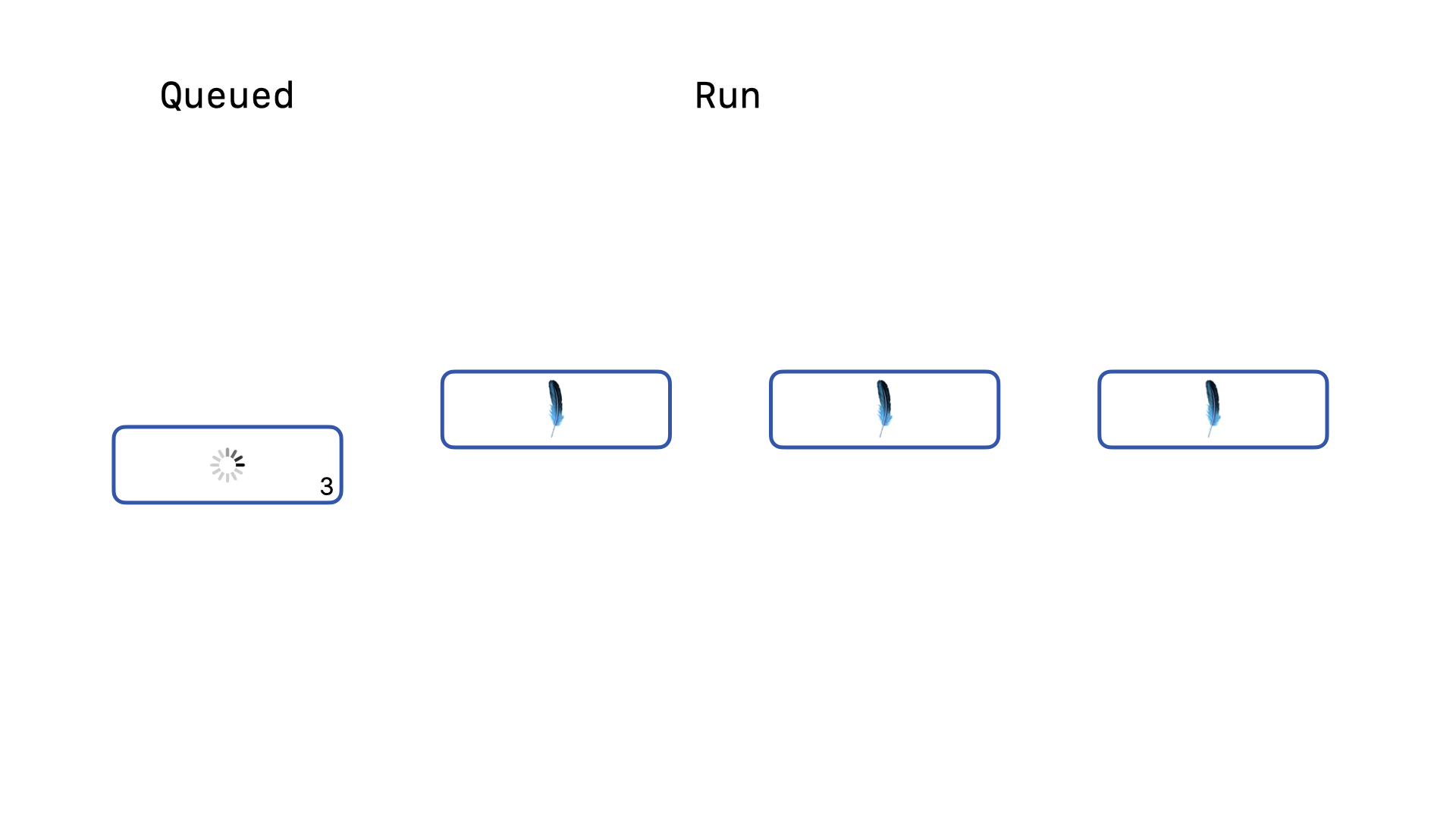

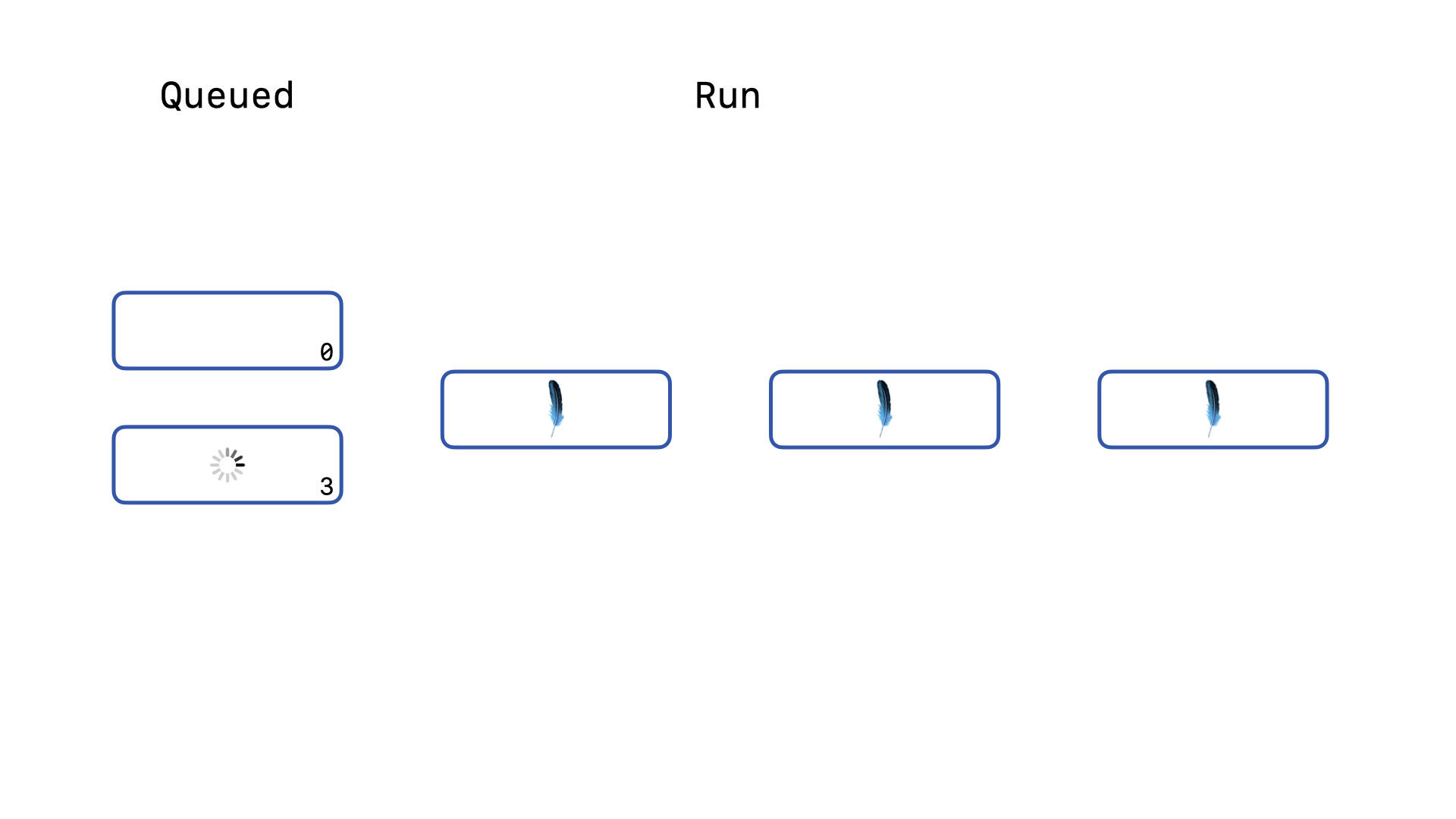

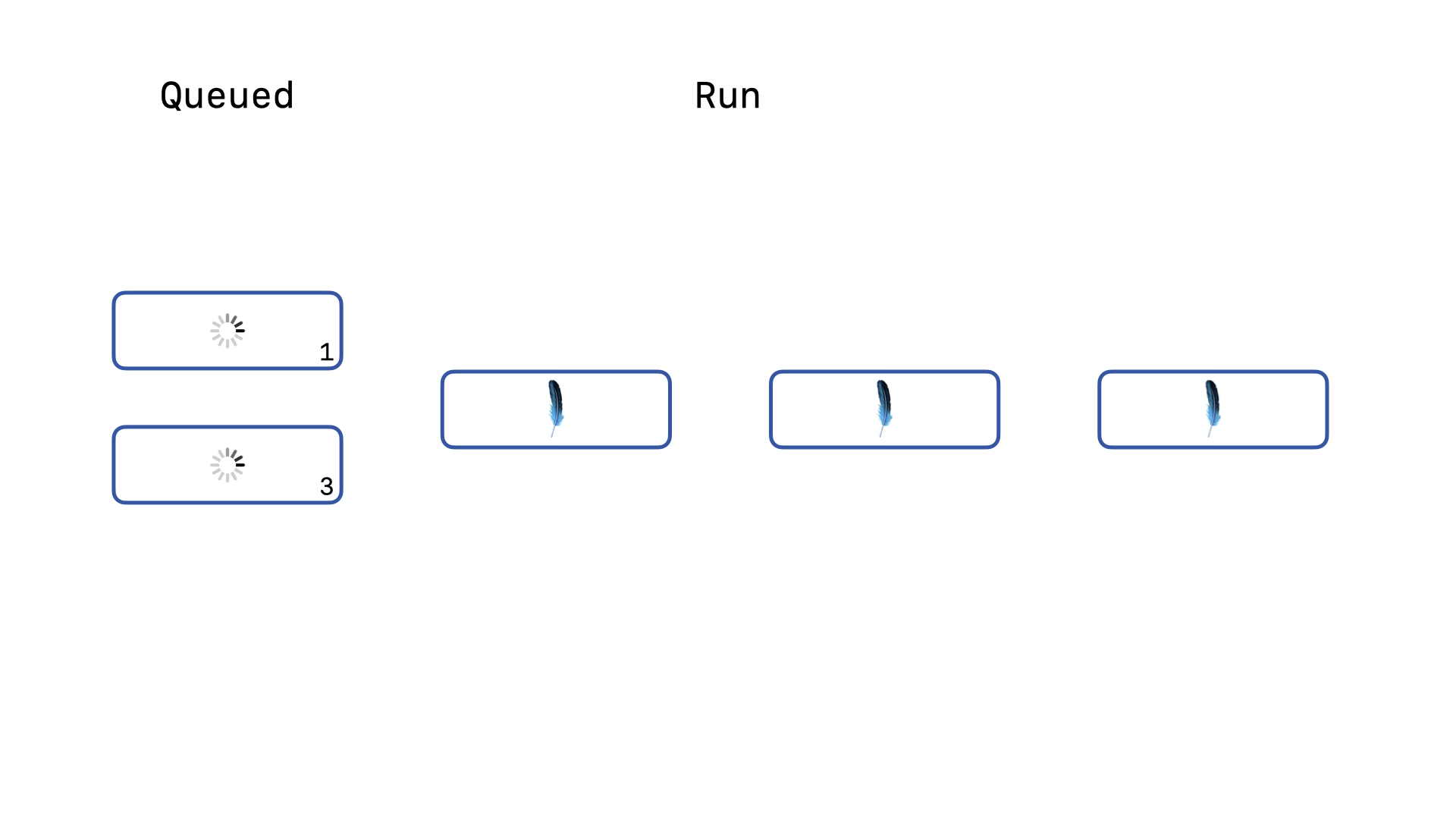

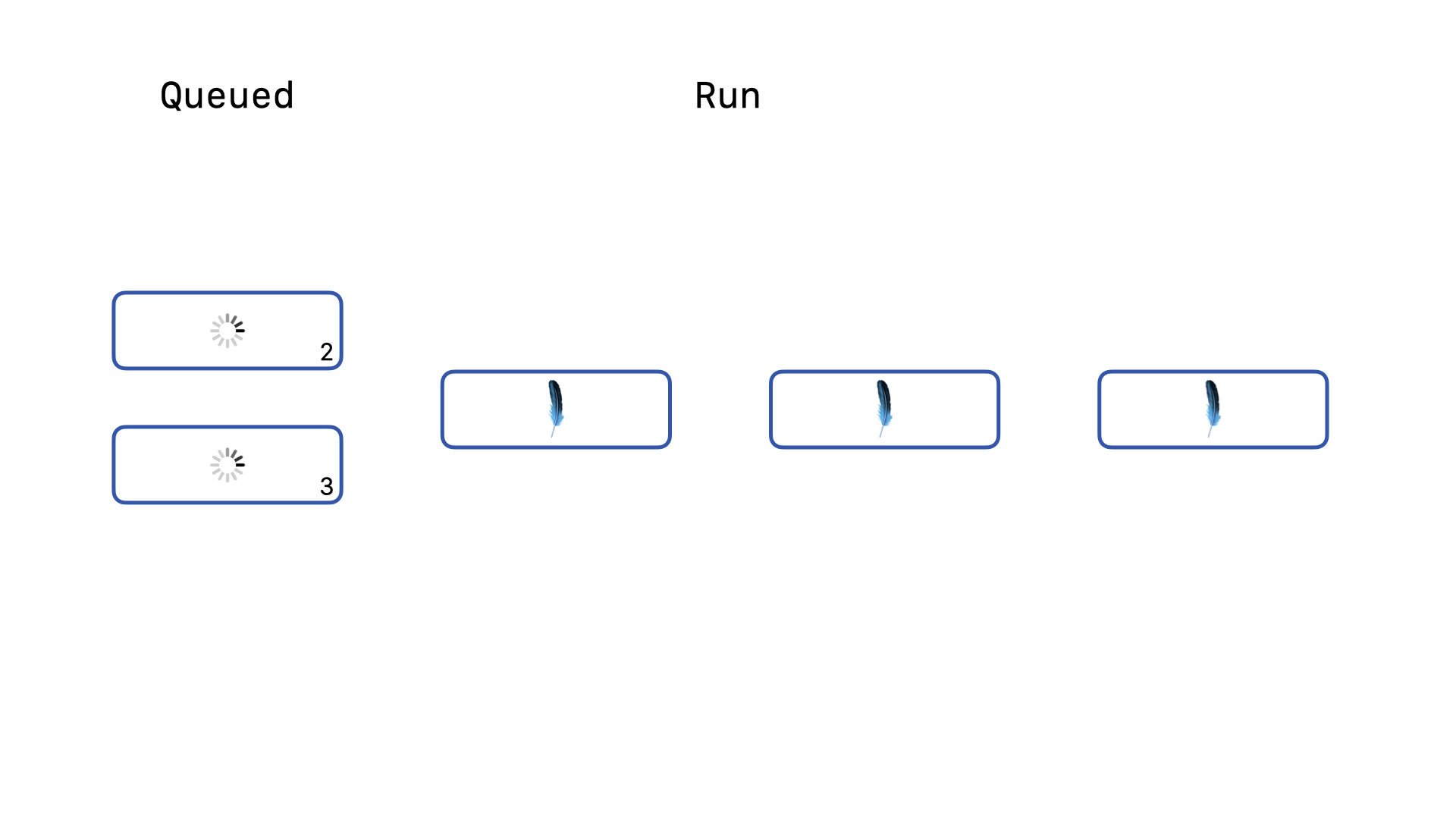

Imagine our application sends 4 write queries to the database at the same moment.

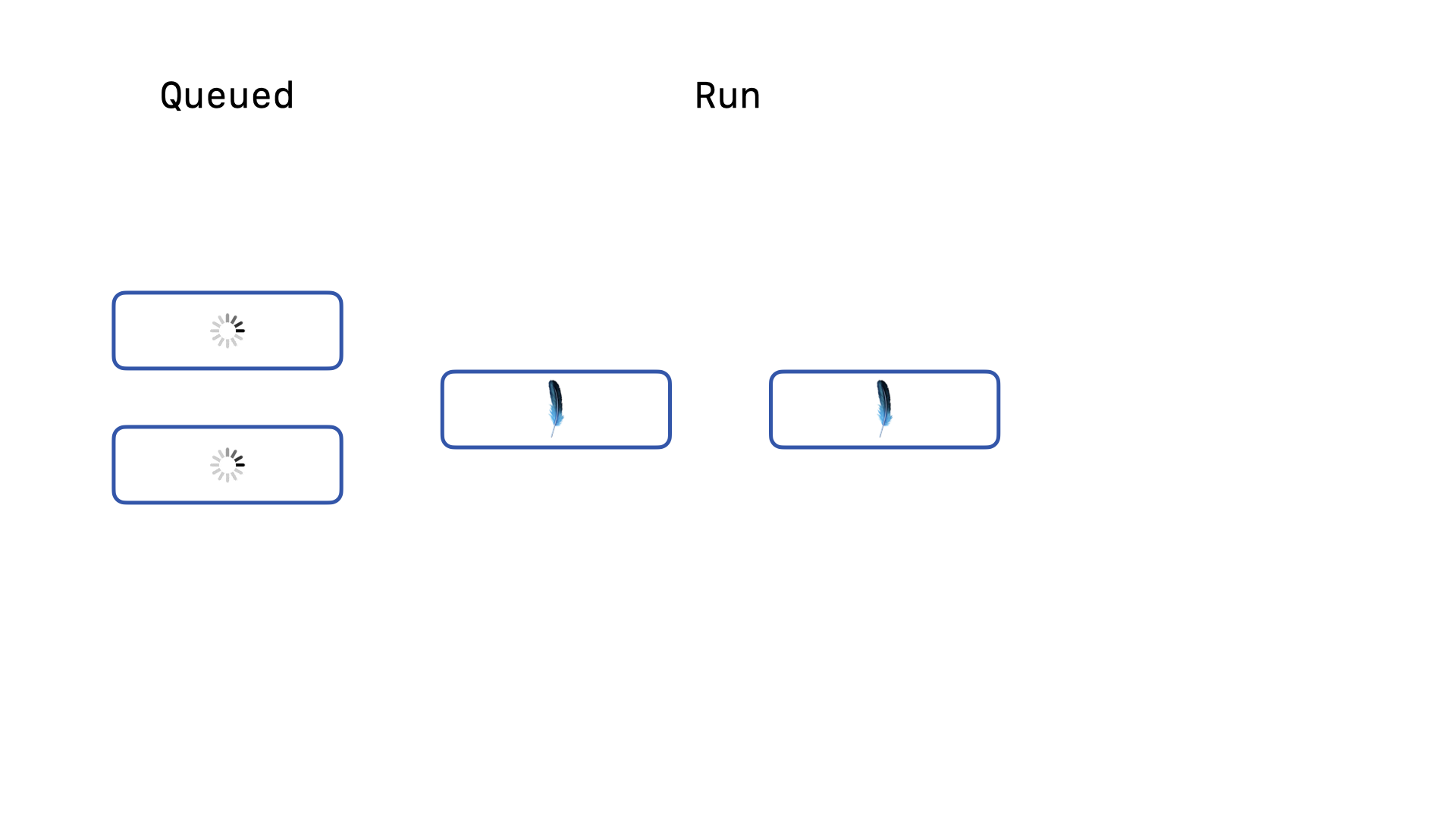

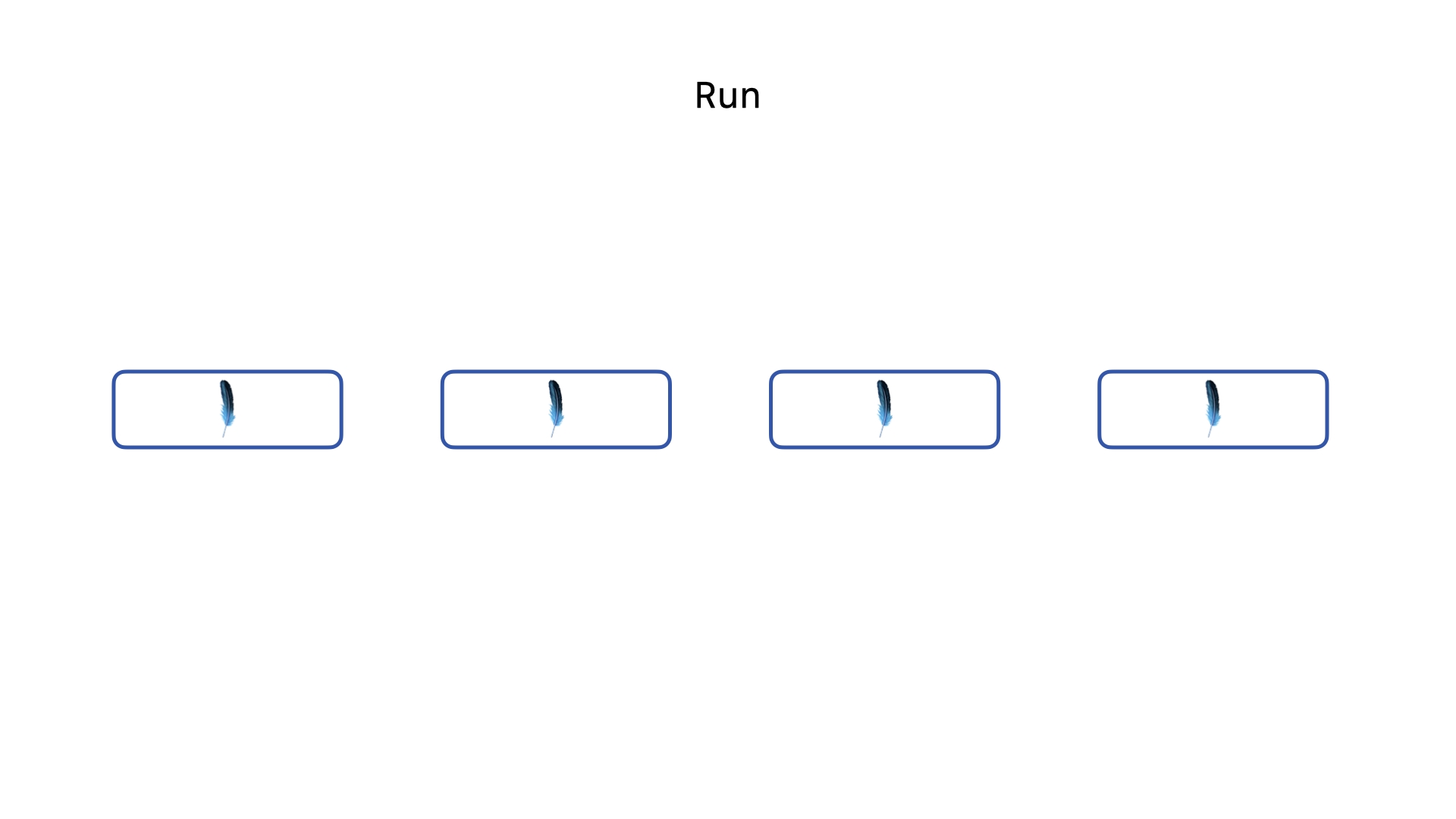

One of those four will acquire the write lock first and run. The other three will be queued, running the backoff re-acquire logic. Once the first write query completes, …

… one of the queued queries will attempt to re-acquire the lock and successfully acquire the lock and start running. The other two queries will continue to stay queued and keep running the backoff re-acquire logic. Again, when the second write query completes, …

… another query will have its backoff re-acquire logic succeed and will start running. Our last query is still queued and still running its backoff re-acquire logic.

Once the third query completes, our final query can acquire the write lock and run. So long as no query is forced to wait for longer than the timeout duration, SQLite will resolve the linear order of write operations on its own. This queuing mechanism is essential to avoiding SQLITE_BUSY exceptions. But, there is a major performance bottleneck lurking in the details of this feature for Rails applications.

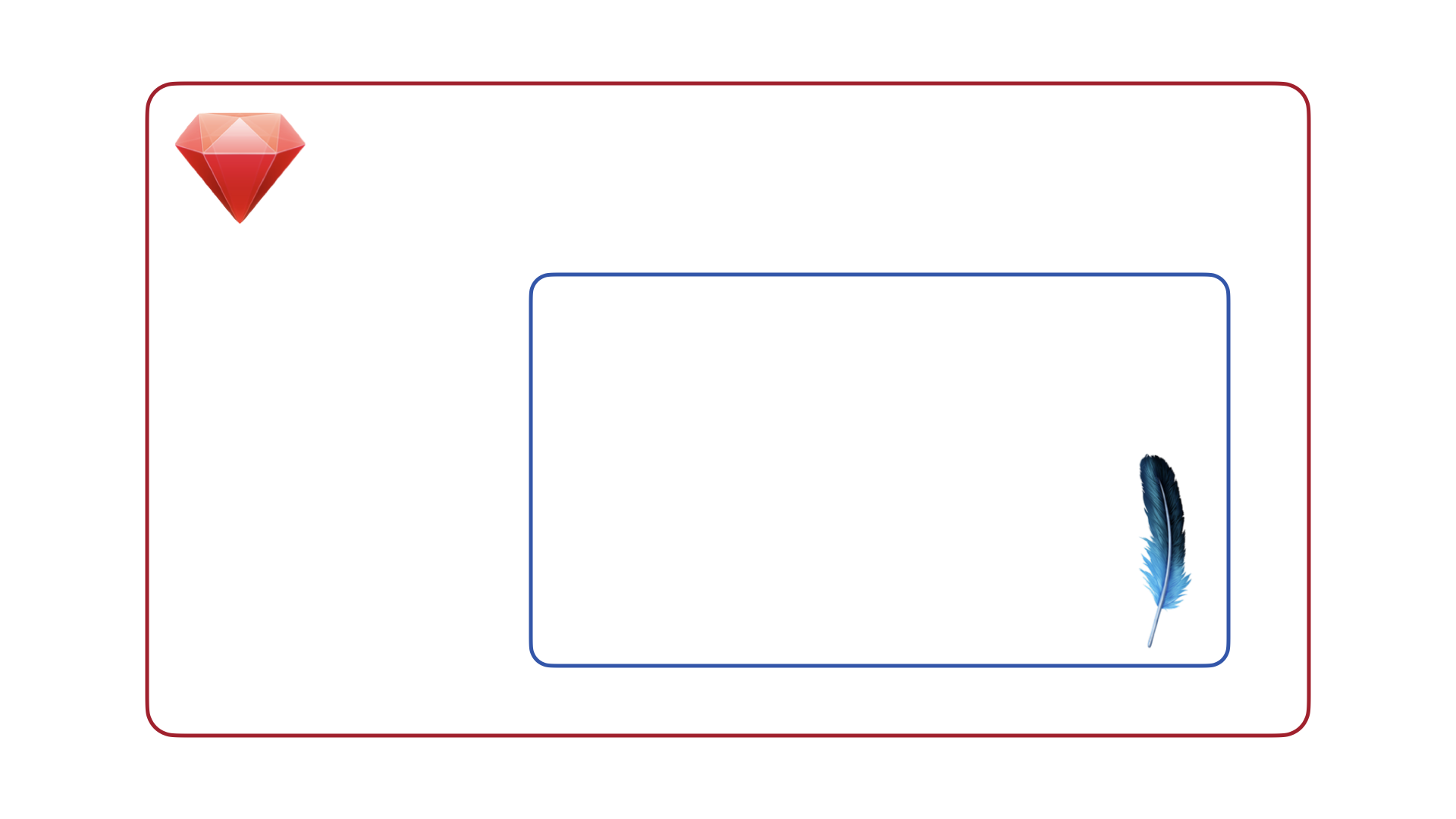

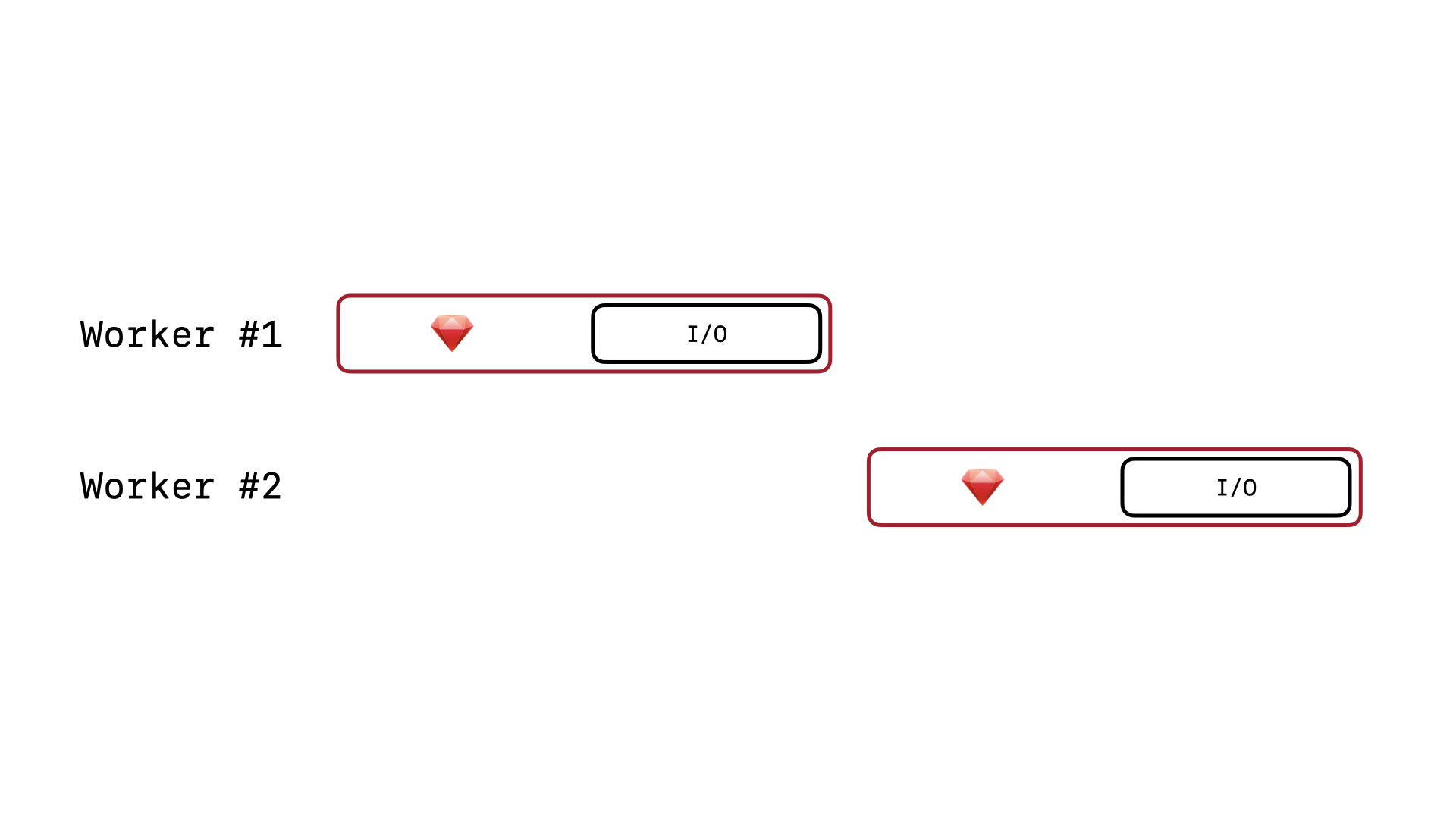

Because SQLite is embedded within your Ruby process and the thread that spawns it, care must be taken to release Ruby’s global VM lock (GVL) when the Ruby-to-SQLite bindings execute SQLite’s C code. By design, the sqlite3-ruby gem does not release the GVL when calling SQLite. For the most part, this is a reasonable decision, but for the busy_timeout, it greatly hampers throughput.

Instead of allowing another Puma worker to acquire Ruby’s GVL while one Puma worker is waiting for the database query to return, that first Puma worker will continue to hold the GVL even while the Ruby operations are completely idle waiting for the database query to resolve and run. This means that concurrent Puma workers won’t even be able to send concurrent write queries to the SQLite database and SQLite’s linear writes will force our Rails app to process web requests somewhat linearly as well. This radically slows down the throughput of our Rails app.

What we want is to allow our Puma workers to be able to process requests concurrently, passing the GVL amongst themselves as they wait on I/O. So, for Rails app using SQLite, this means that we need to unlock the GVL whenever a write query gets queued and is waiting to acquire the SQLite write lock.

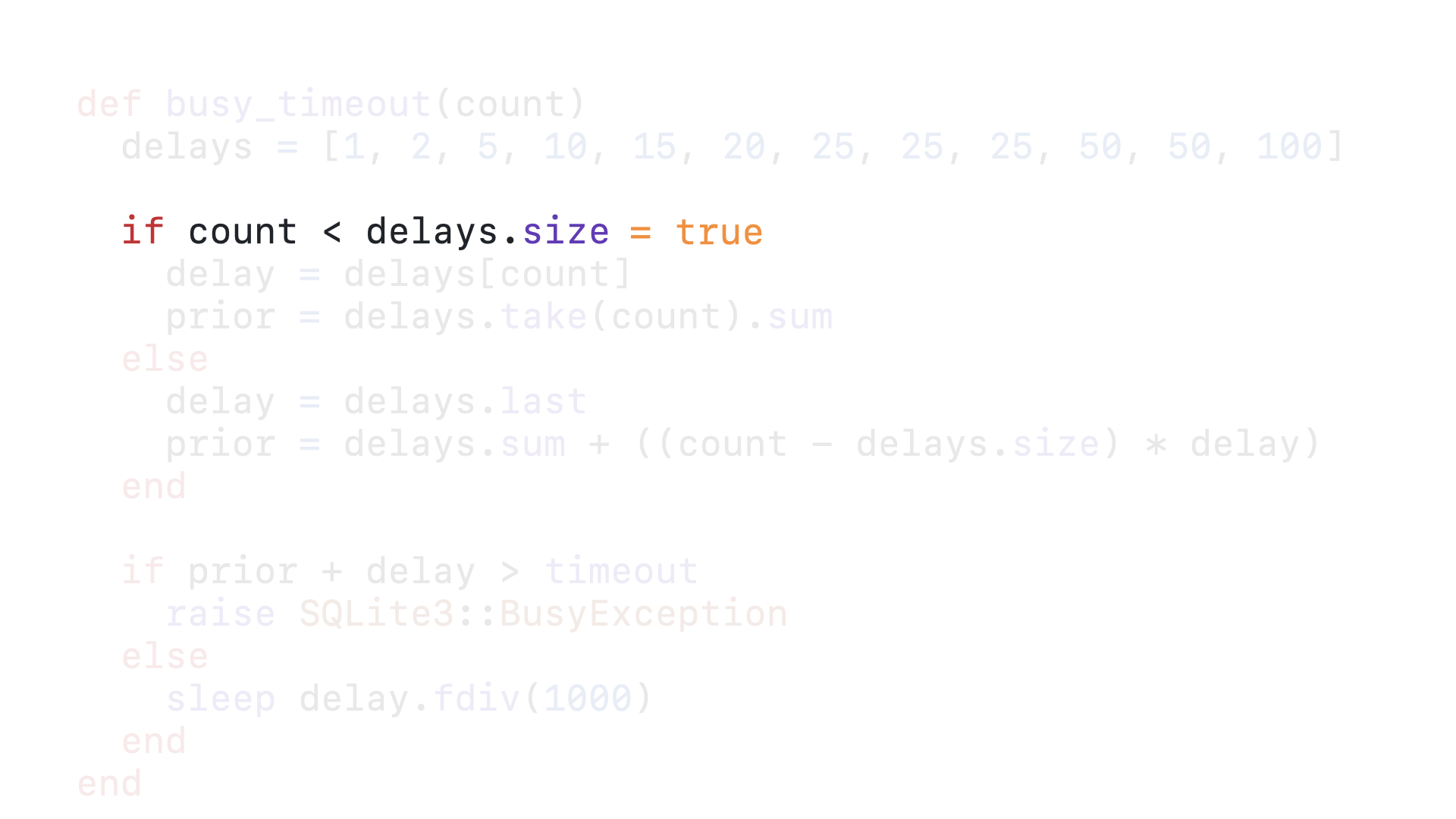

Luckily, in addition to the busy_timeout, SQLite also provides the lower-level busy_handler hook. The busy_timeout is nothing more than a specific busy_handler implementation provided by SQLite. Any application using SQLite can provide its own custom busy_handler. The sqlite3-ruby gem is a SQLite driver, meaning that it provides Ruby bindings for the C API that SQLite exposes. Since it provides a binding for the sqlite3_busy_handler C function, we can write a Ruby callback that will be called whenever a query is queued.

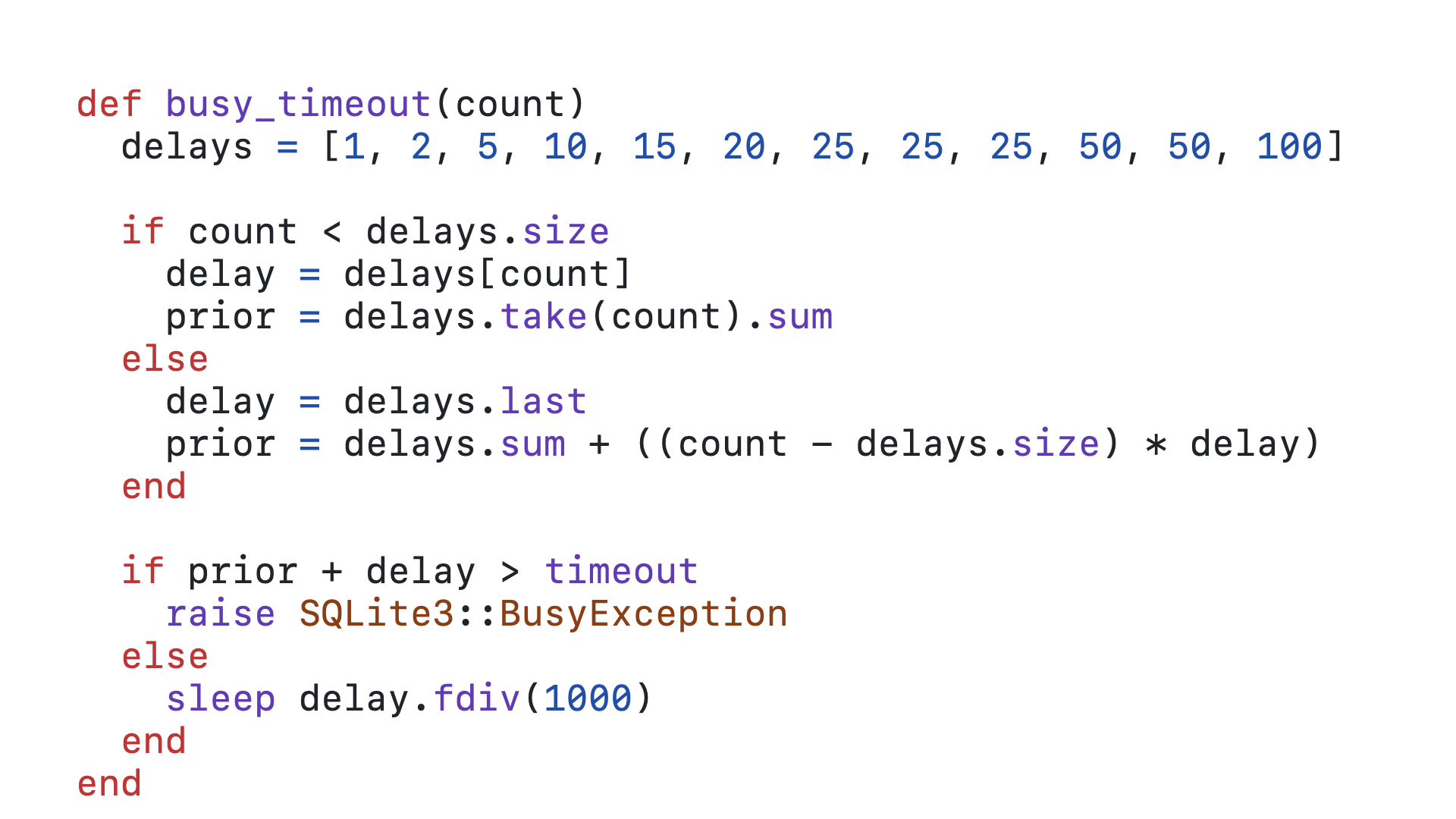

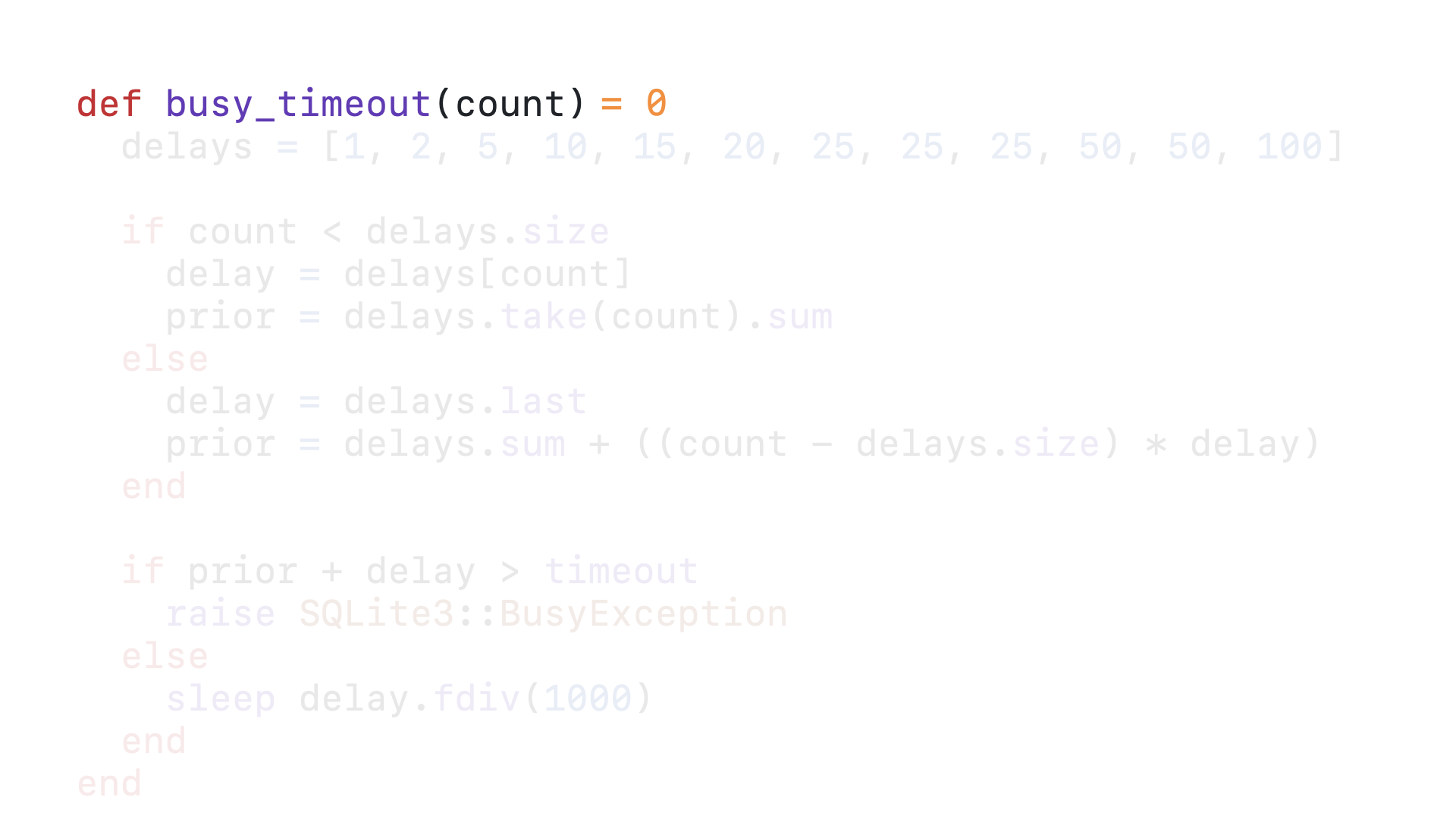

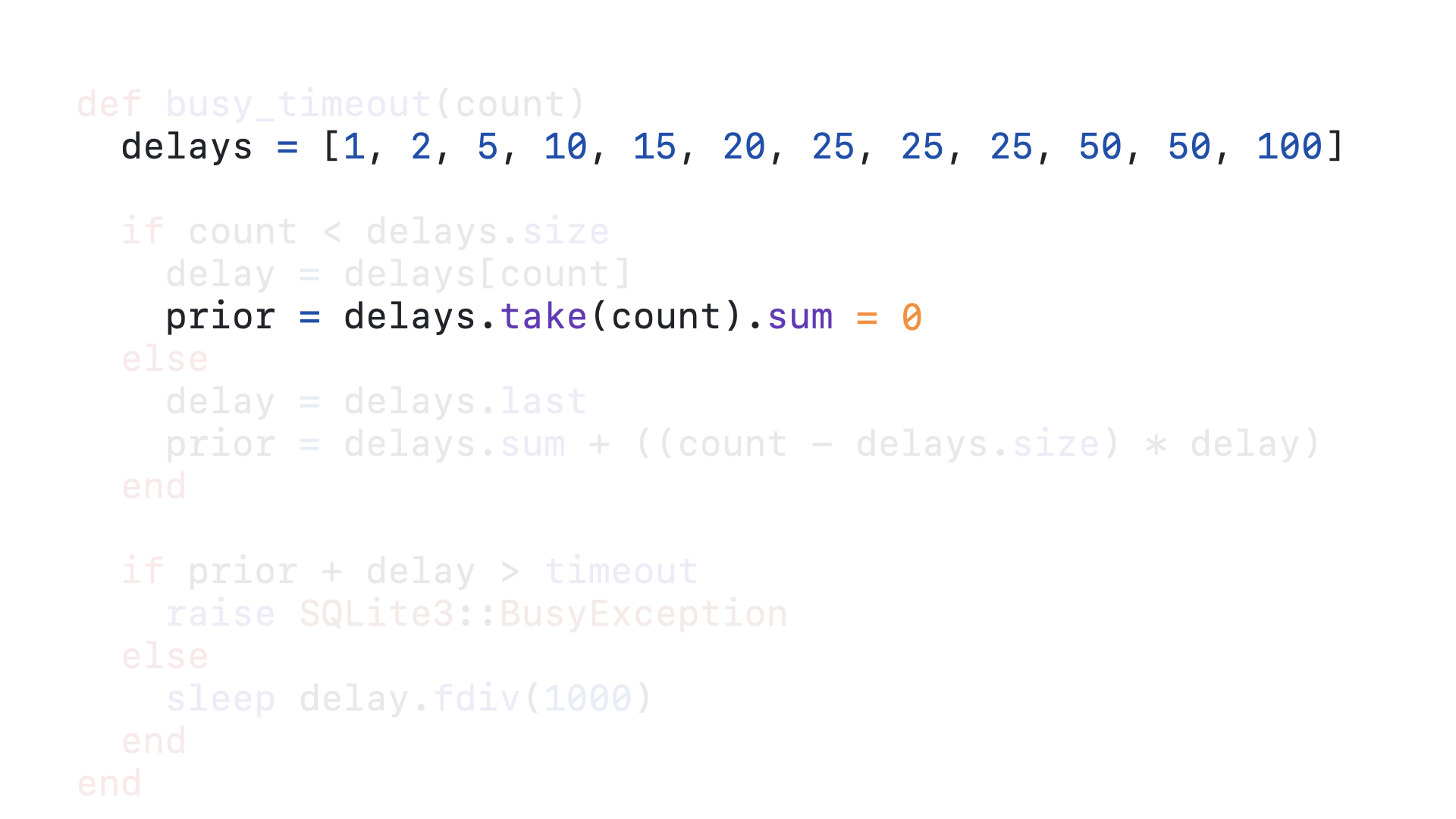

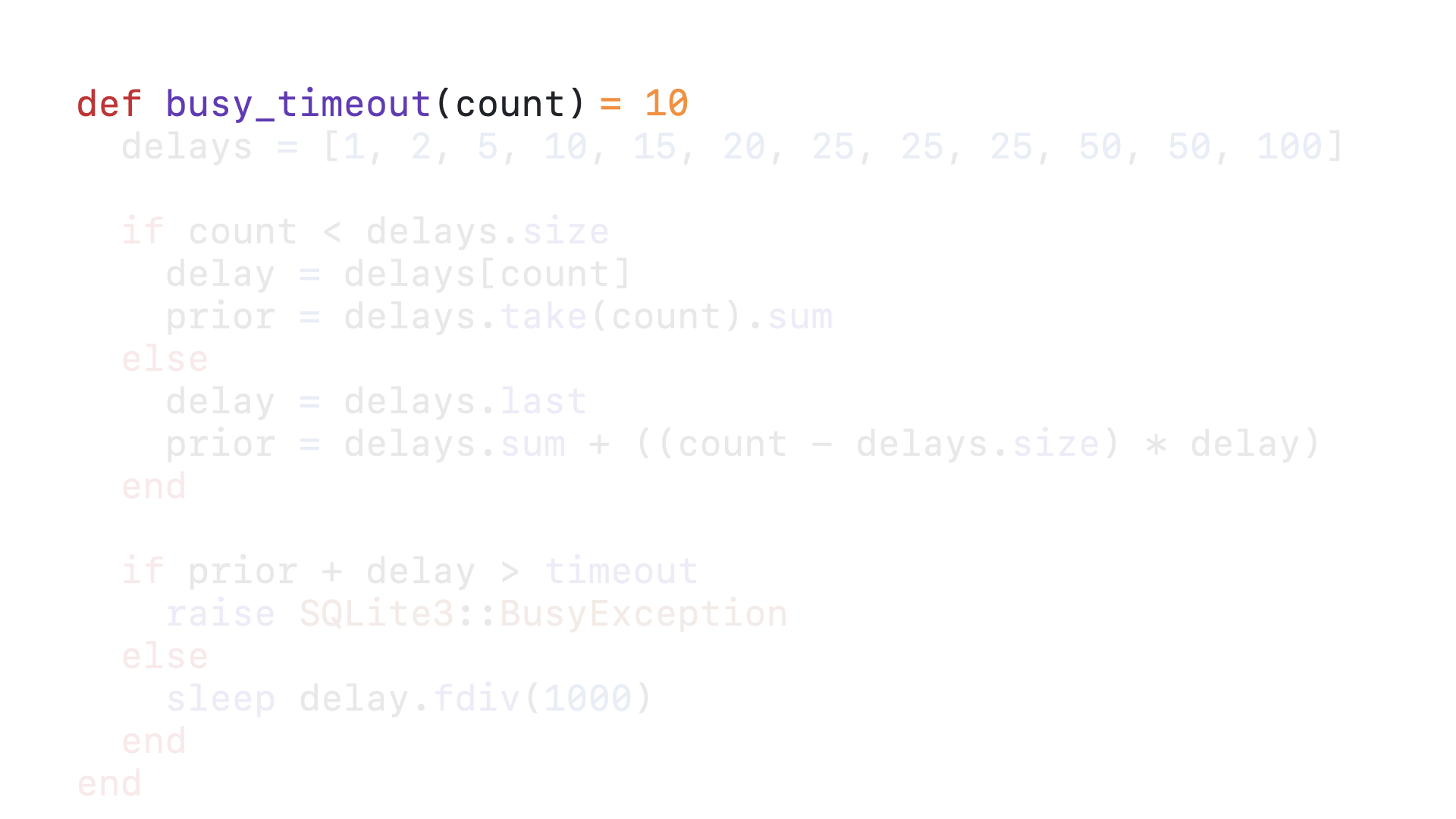

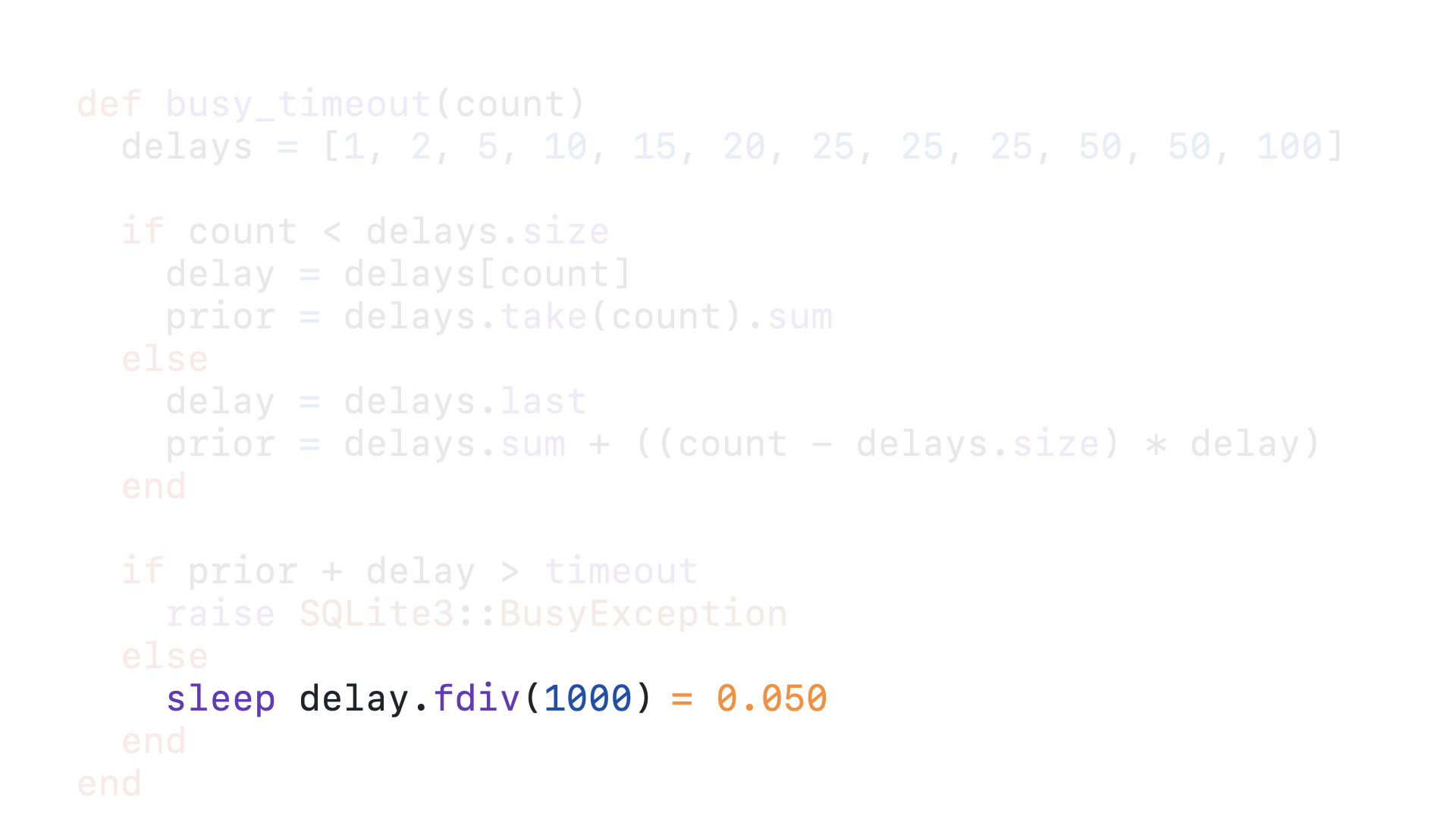

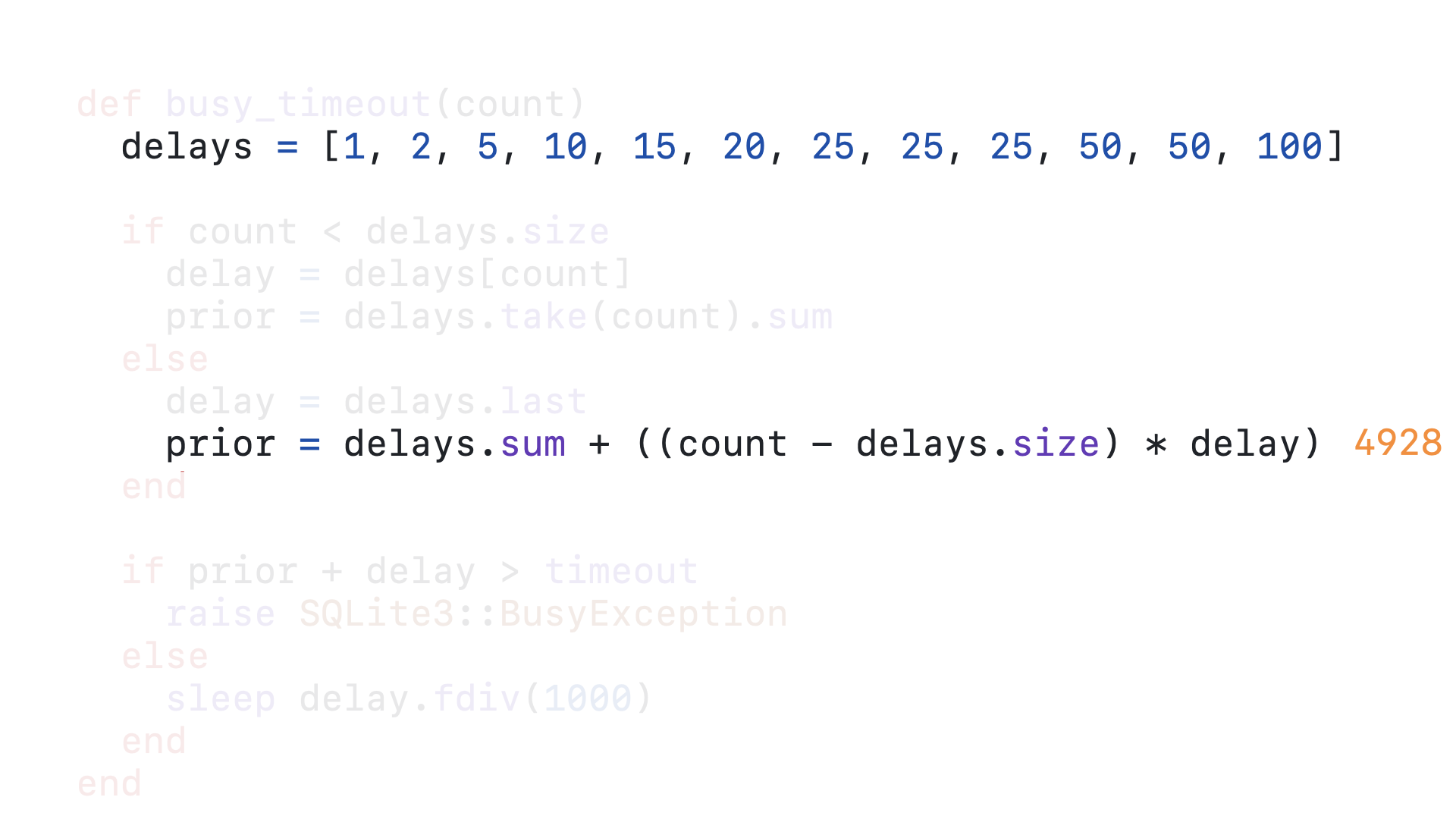

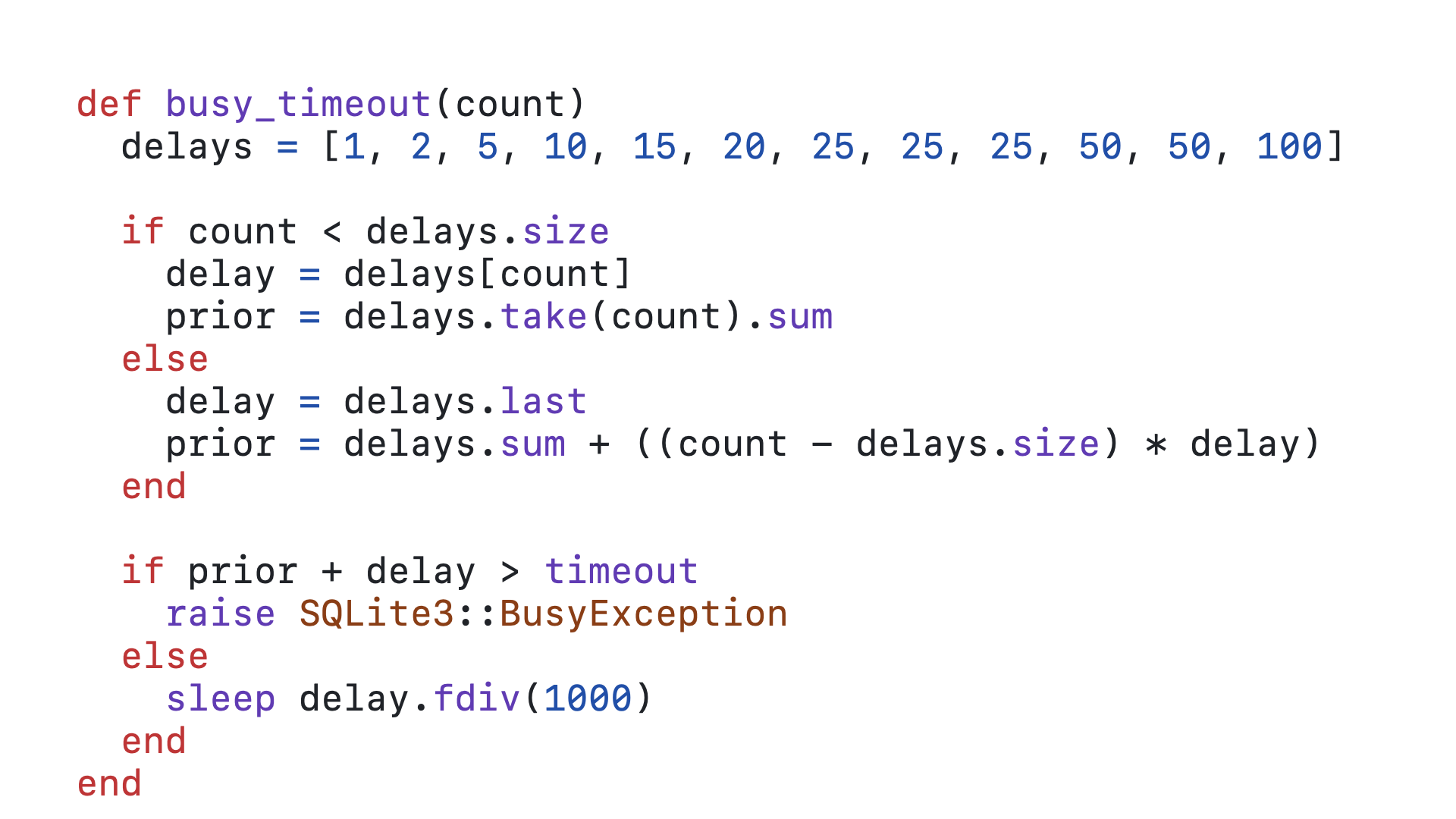

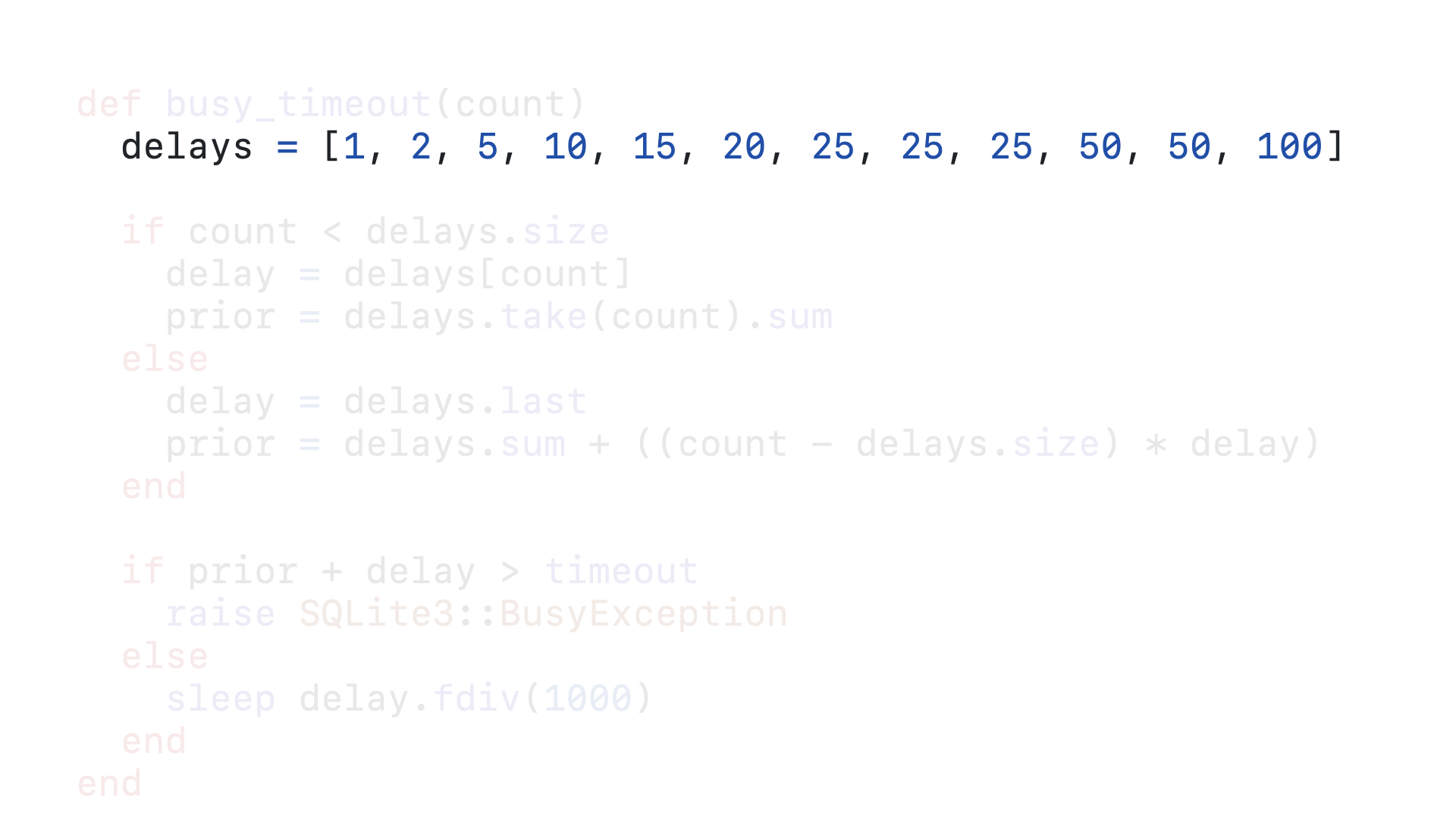

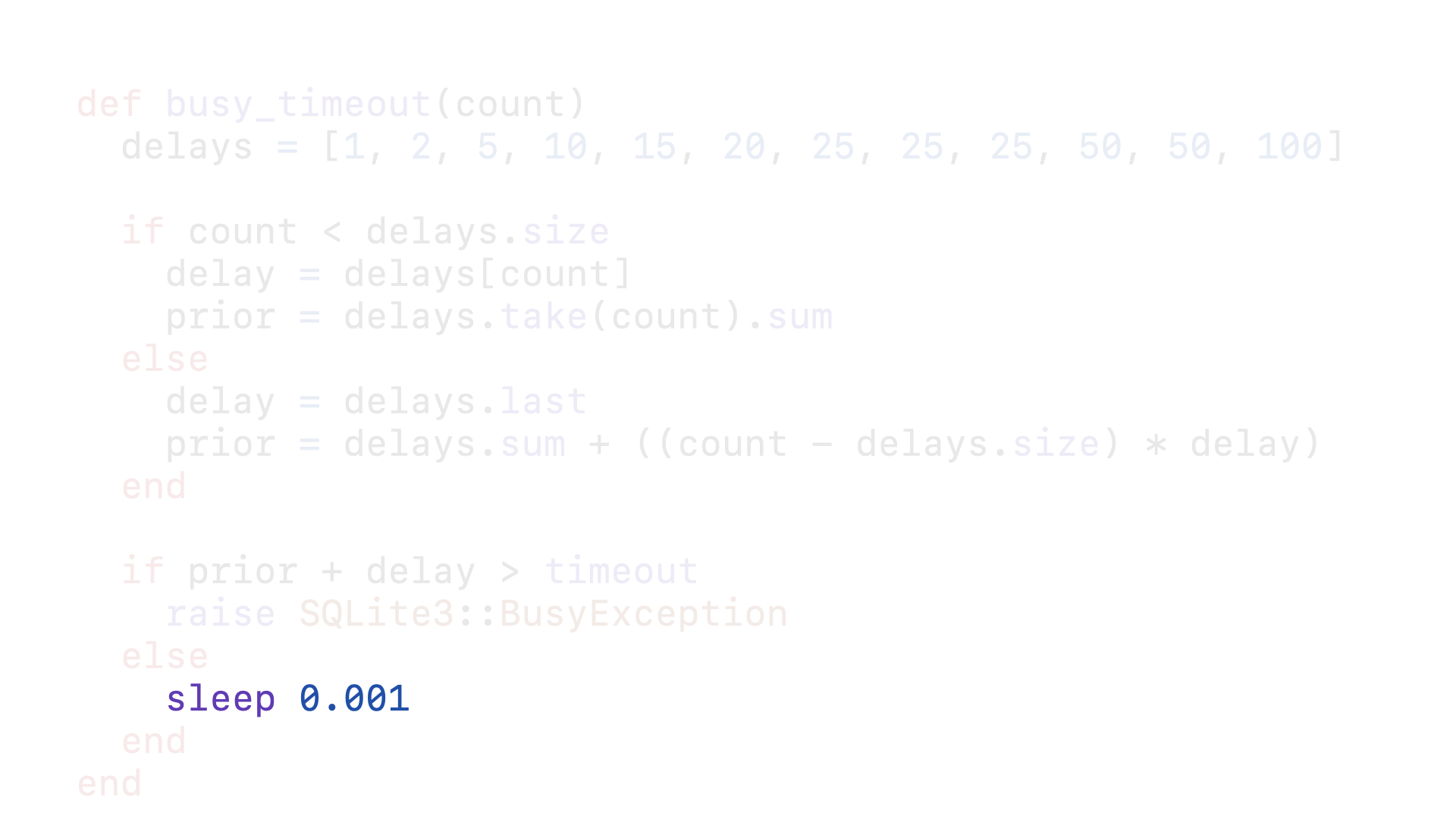

Here is a Ruby implementation of the logic you will find in SQLite’s C source for its busy_timeout. Every time this callback is called, it is passed the count of the number of times this query has called this callback. That count is used to determine how long this query should wait to try again to acquire the write lock and how long it has already waited. By using Ruby’s sleep, we can ensure that the GVL is released while a query is waiting to retry acquiring the lock.

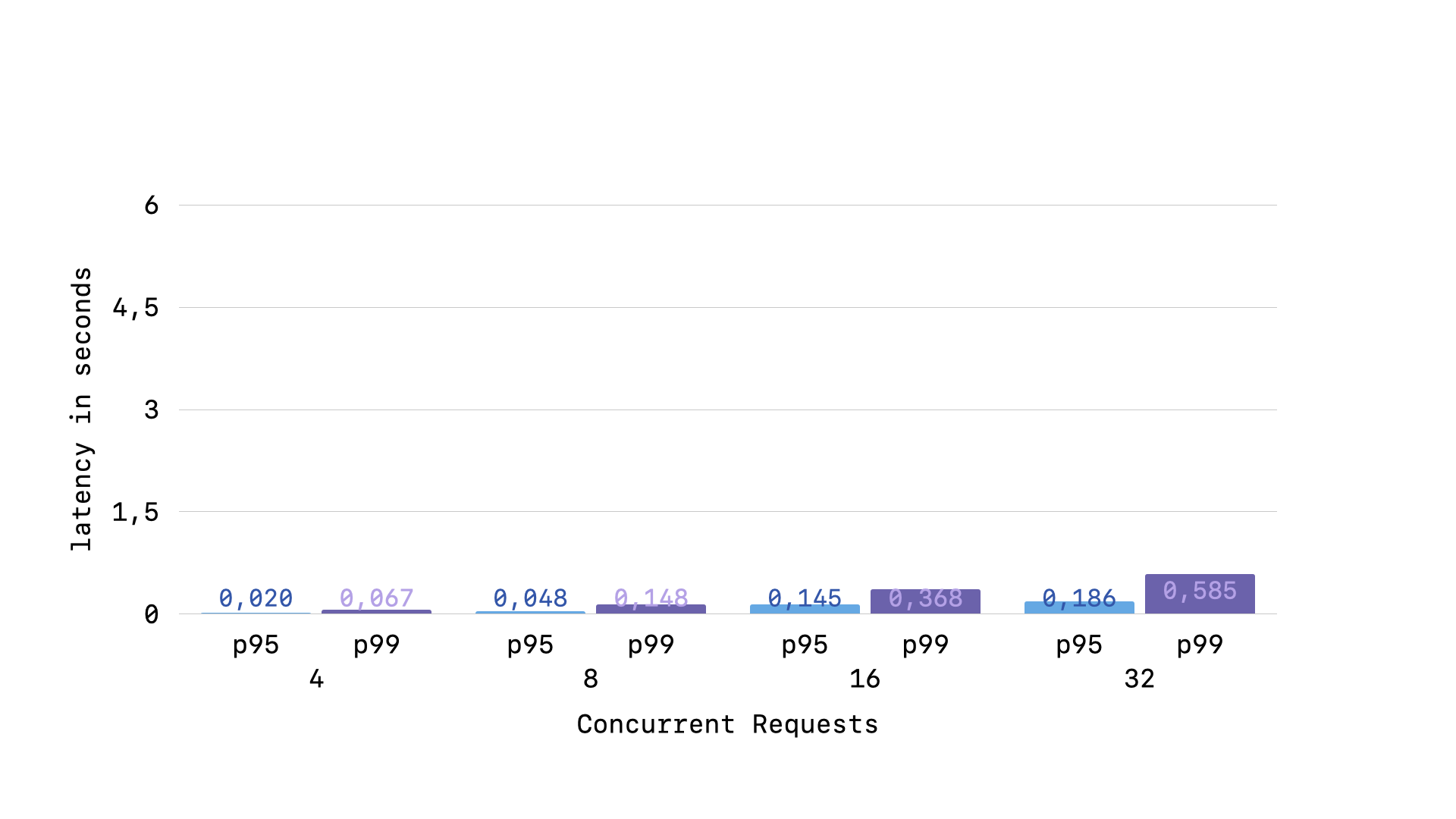

By ensuring that the GVL is released while queries wait to retry acquiring the lock, we have massively improved our p99 latency even when under concurrent load.

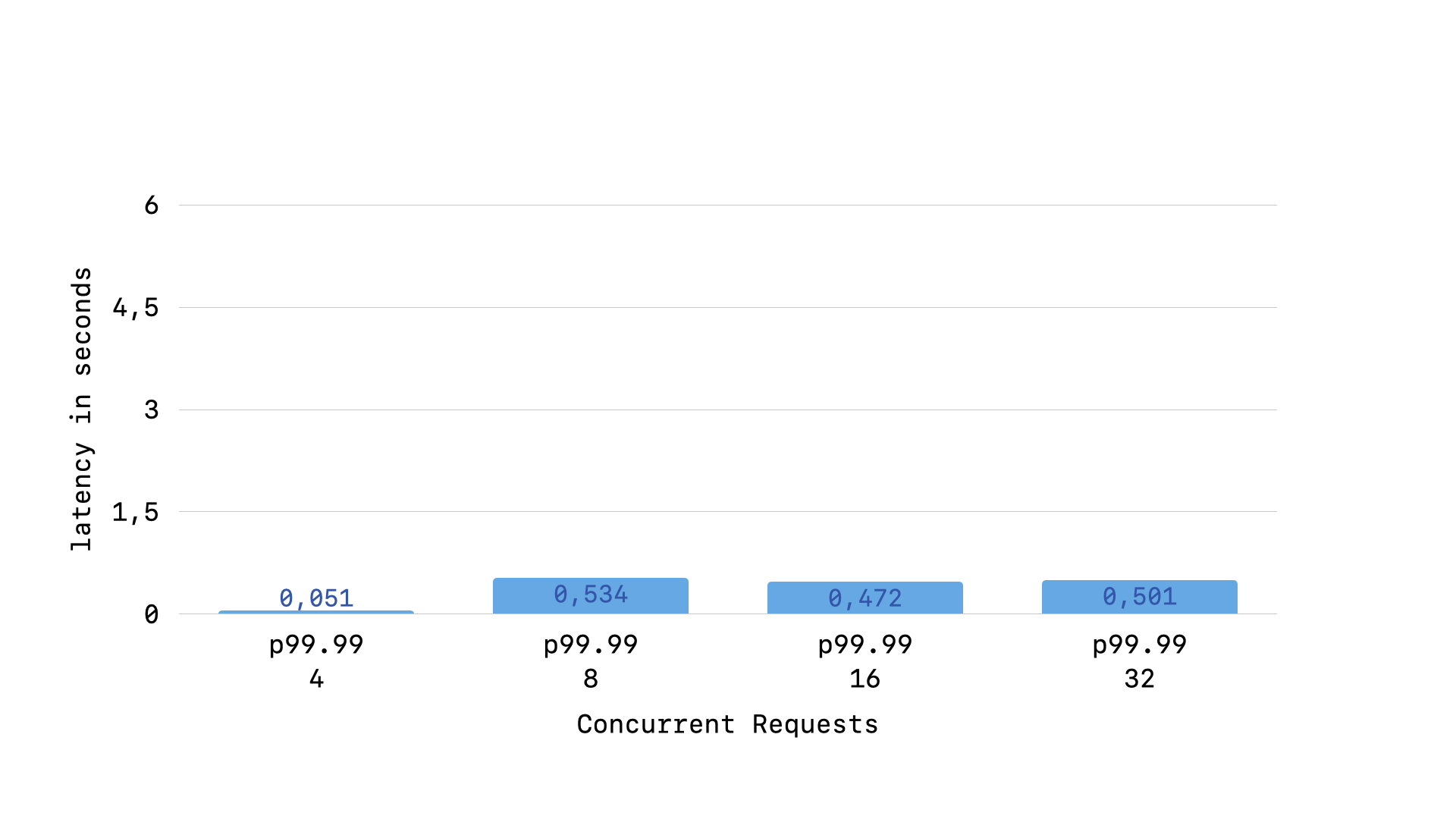

But, there are still some outliers. If we look instead at the p99.99 latency, we will find another steadily increasing graph.

Our slowest queries get steadily slower the more concurrent load our application is under. This is another growth curve that we would like to flatten. But, in order to flatten it, we must understand why it is occurring.

The issue is that our Ruby re-implementation of SQLite’s busy_timeout logic penalizes “older queries”. This is going to kill our long-tail performance, as responses will get naturally segmented into the batch that had “young” queries and those that had “old” queries, because SQLite will naturally segment queries into such batches. To explain more clearly what I mean, let’s step through our Ruby busy_timeout logic a couple times.

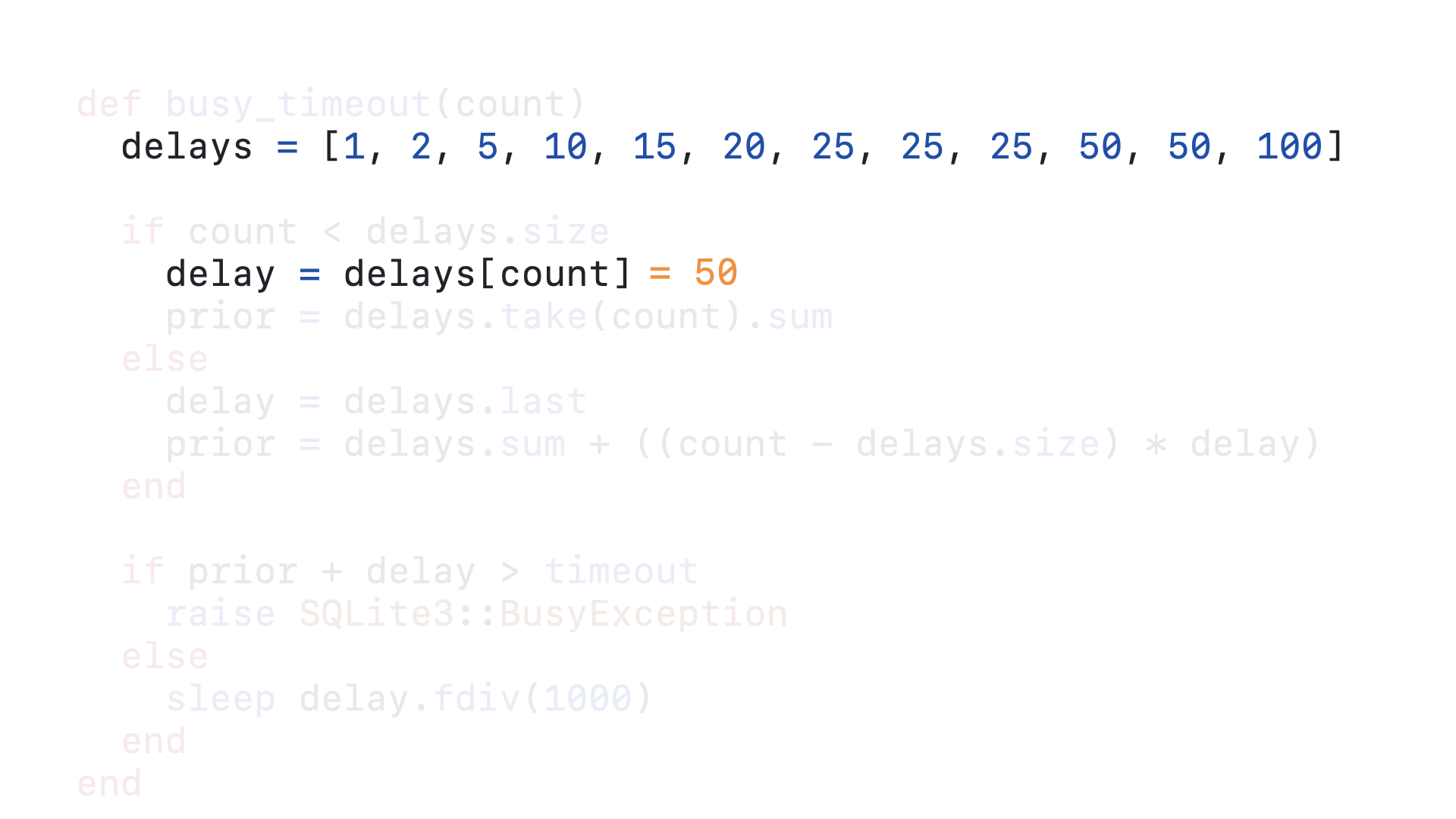

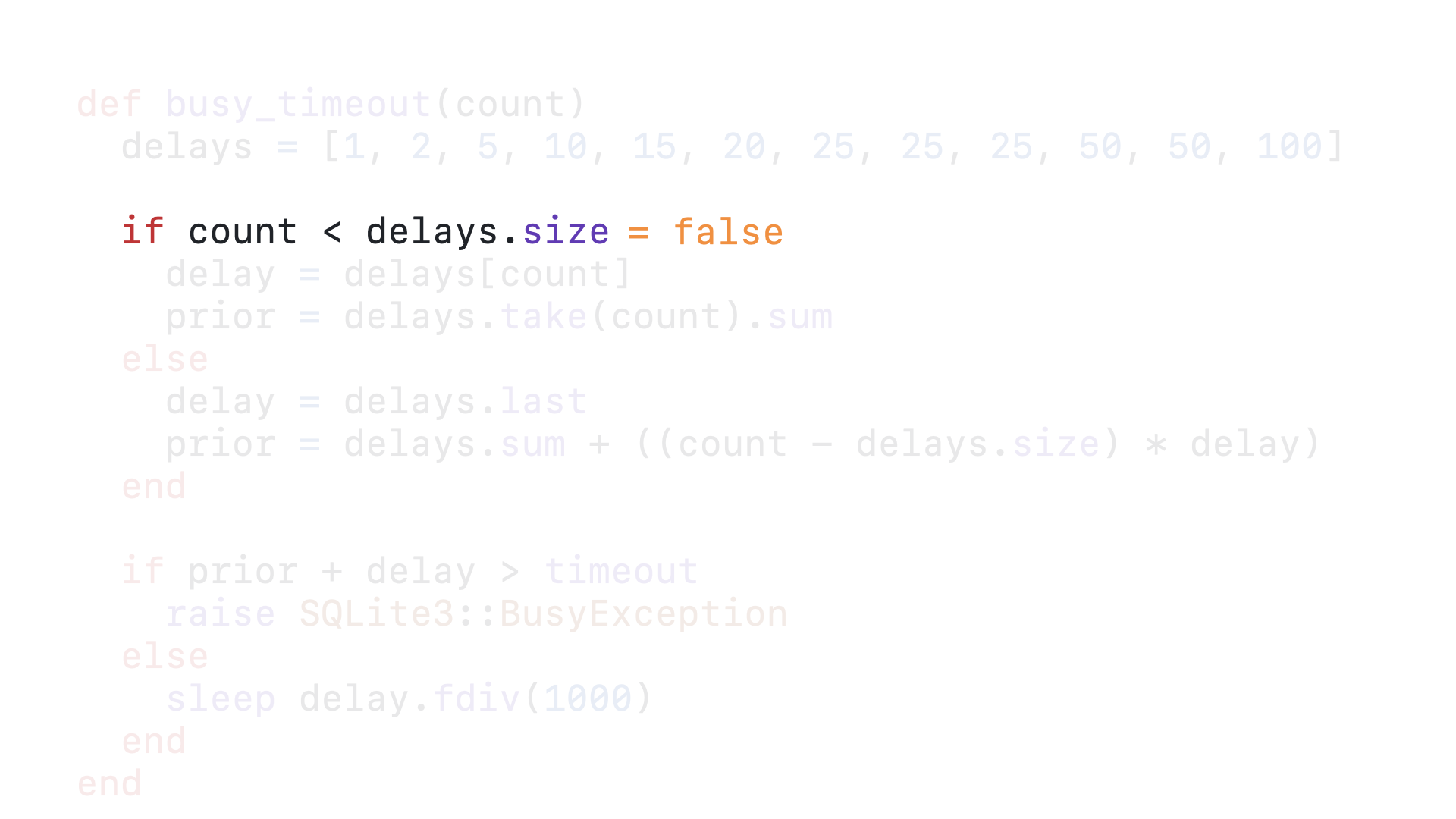

The first time a query is queued and calls this timeout callback, the count is zero.

And since 0 is less than 12, we enter the if block.

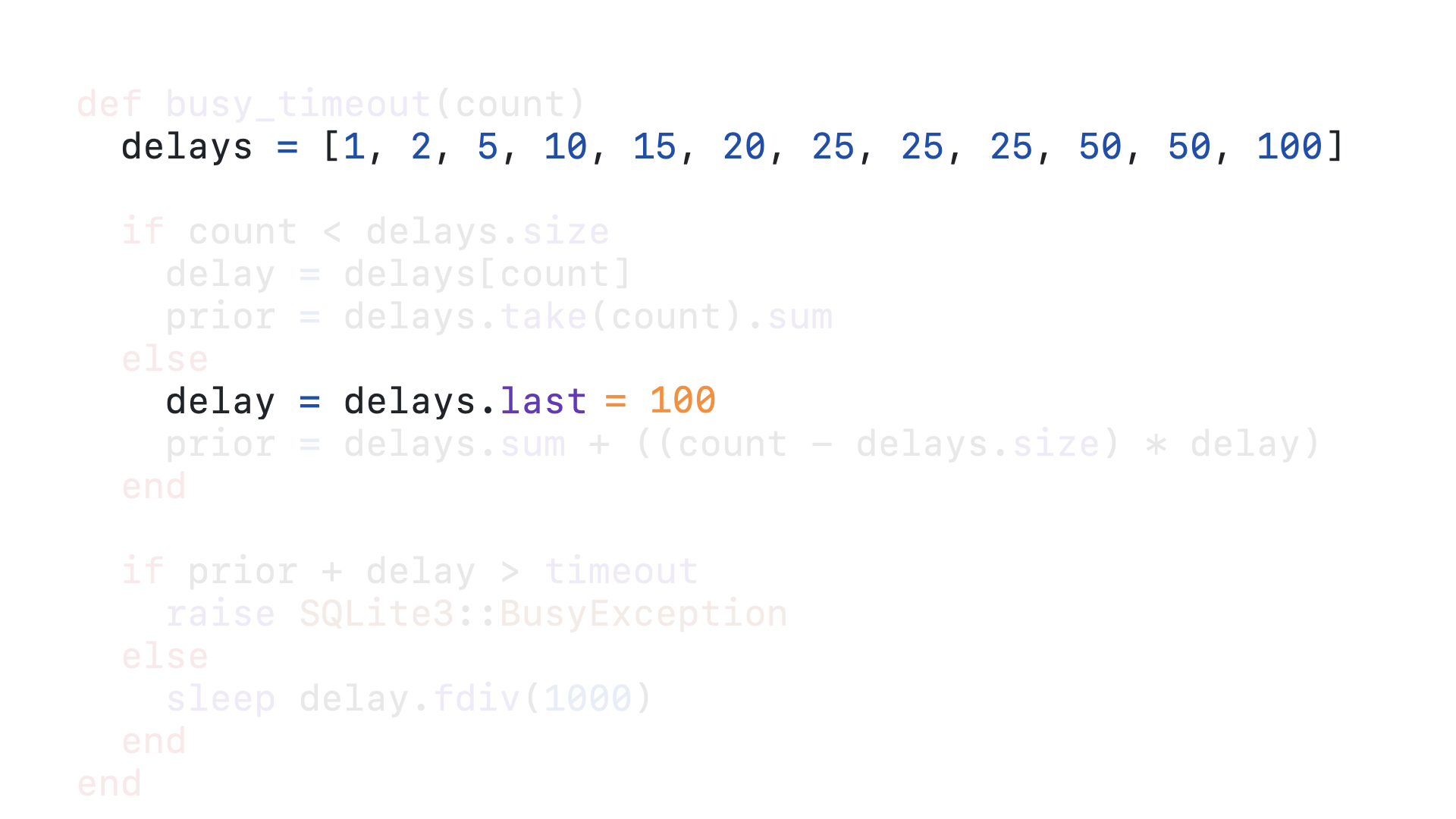

We get the zero-th element in the delays array as our delay, which is 1.

We then take the first 0 elements of the delays array, which is an empty array, and sum those numbers together, which in this case sums to 0. This is how long the query has been delayed for already,

With our timeout as 5000, 0 + 1 is not greater than 5000, so we fall through to the else block.

And we sleep for 1 millisecond before this callback is called again.

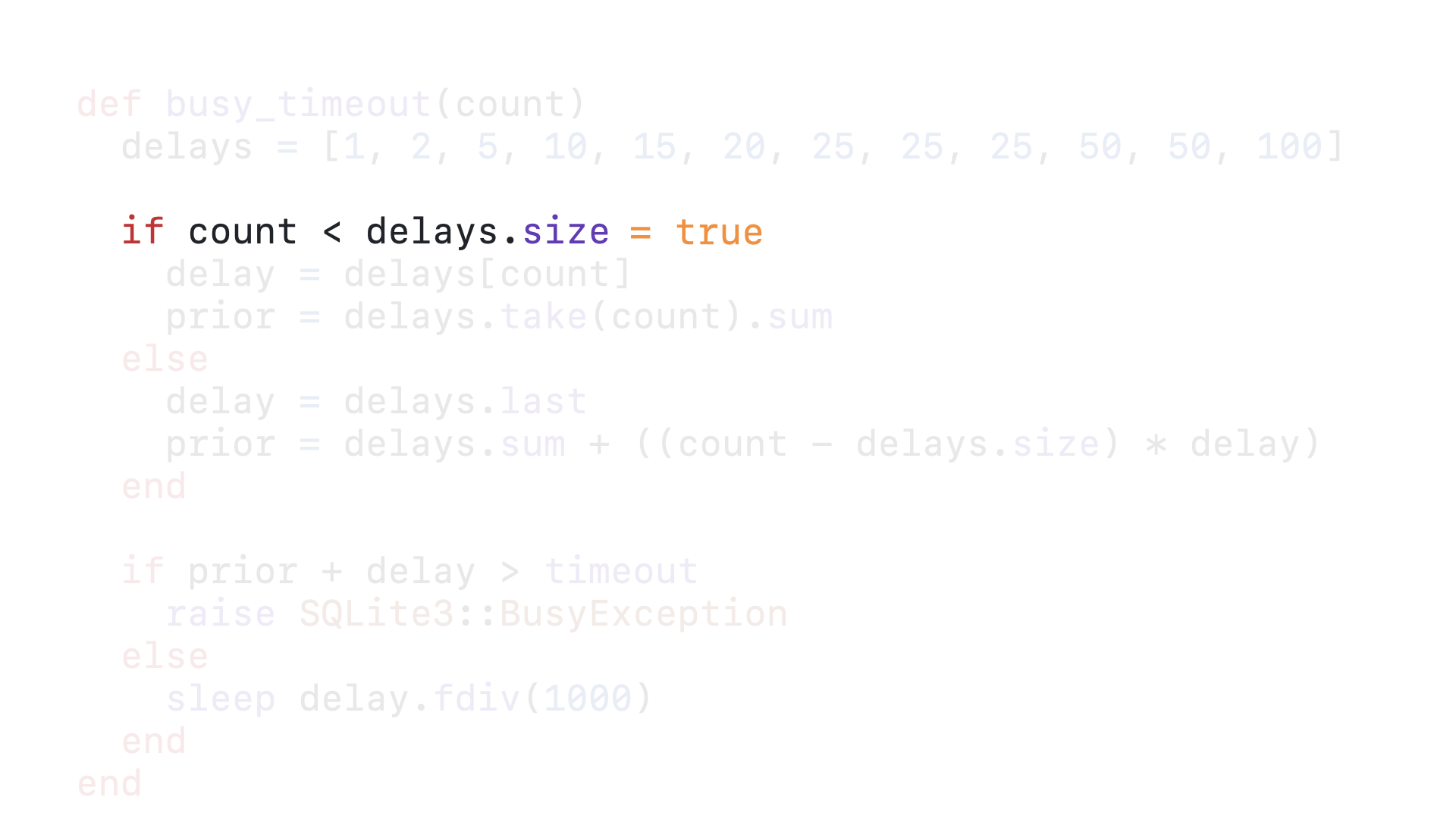

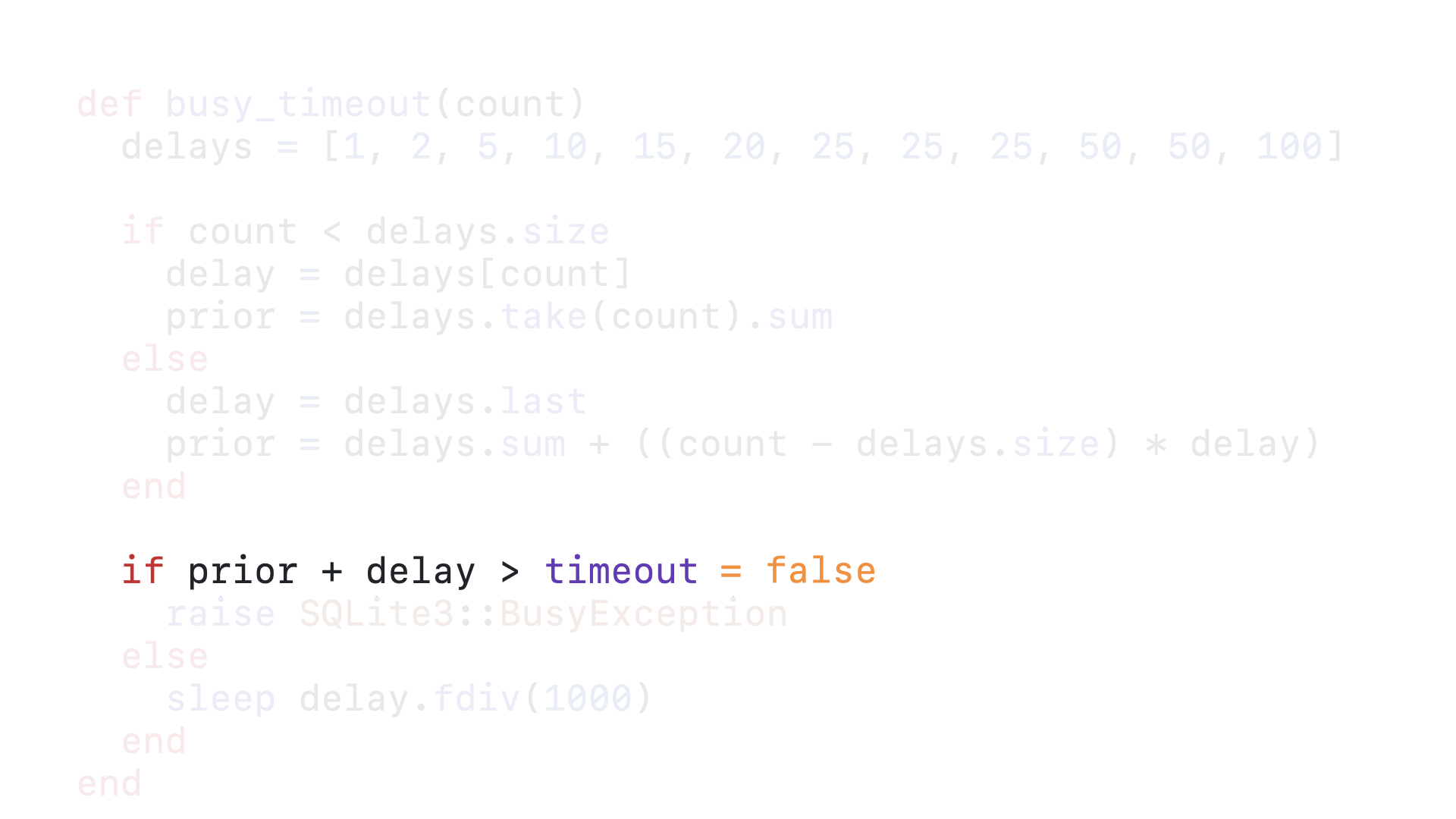

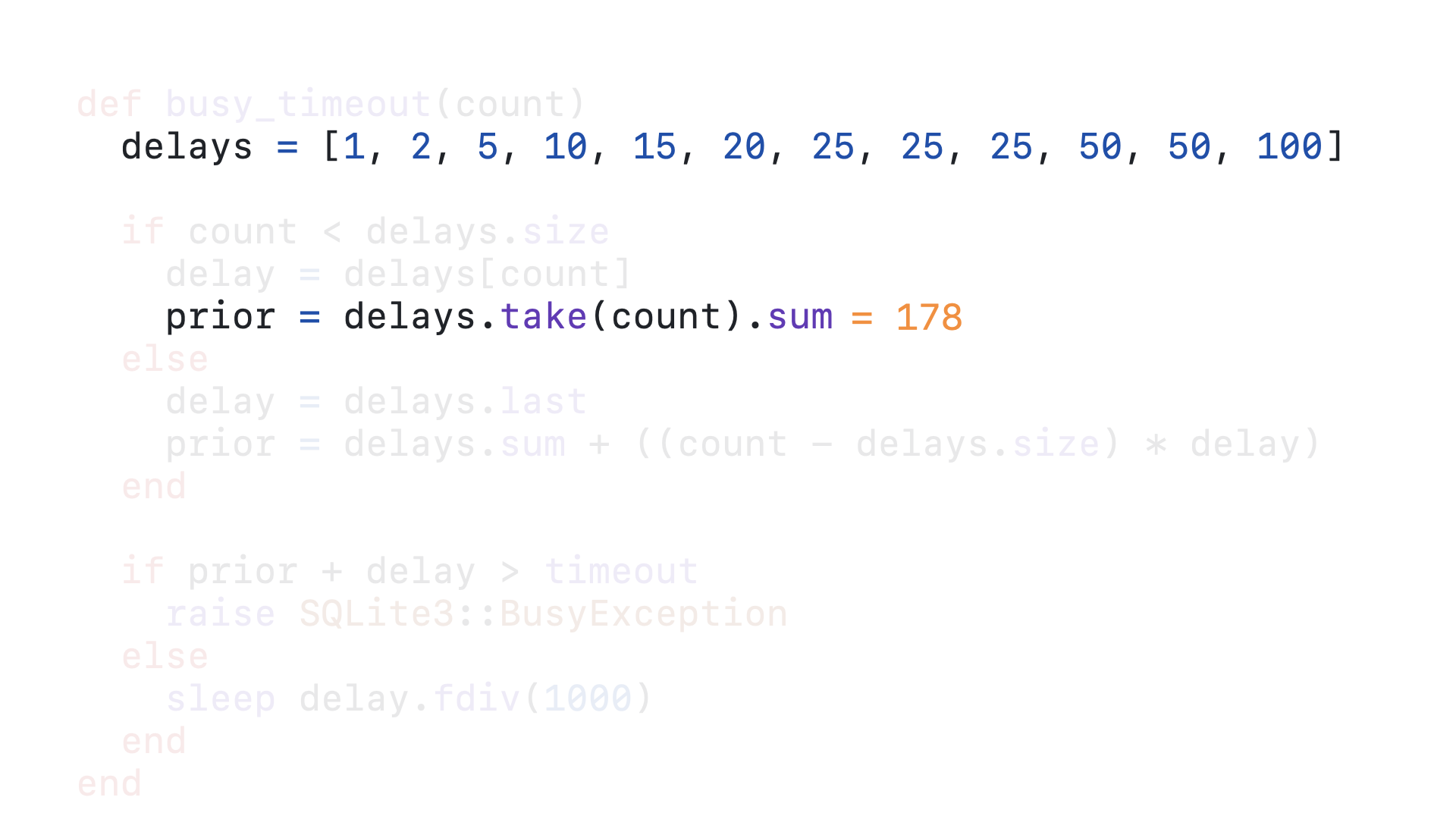

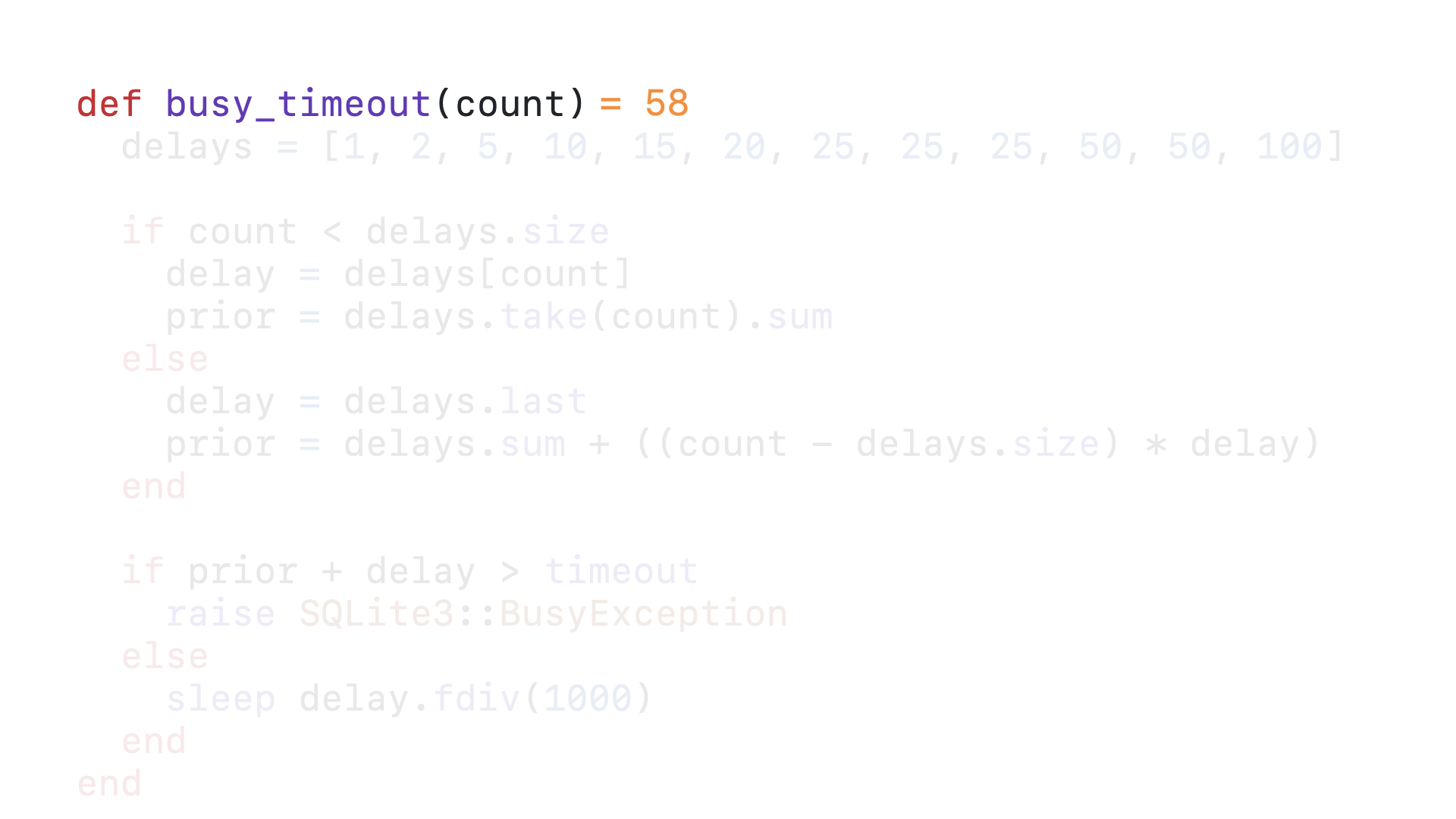

The tenth time this query calls this timeout callback, the count is, well, 10.

10 is still less than 12, so we enter the if block.

We get the tenth element in the delays array as our delay, which is 50.

We then take the first 10 elements of the delays array, that is the everything in the array up to but not including the tenth element, and sum those numbers together, which in this case sums to 178. This is how long the query has been delayed for already.

50 + 178 is still not greater than 5000, so we fall through to the else block.

And now we sleep for 50 milliseconds before this callback is called again.

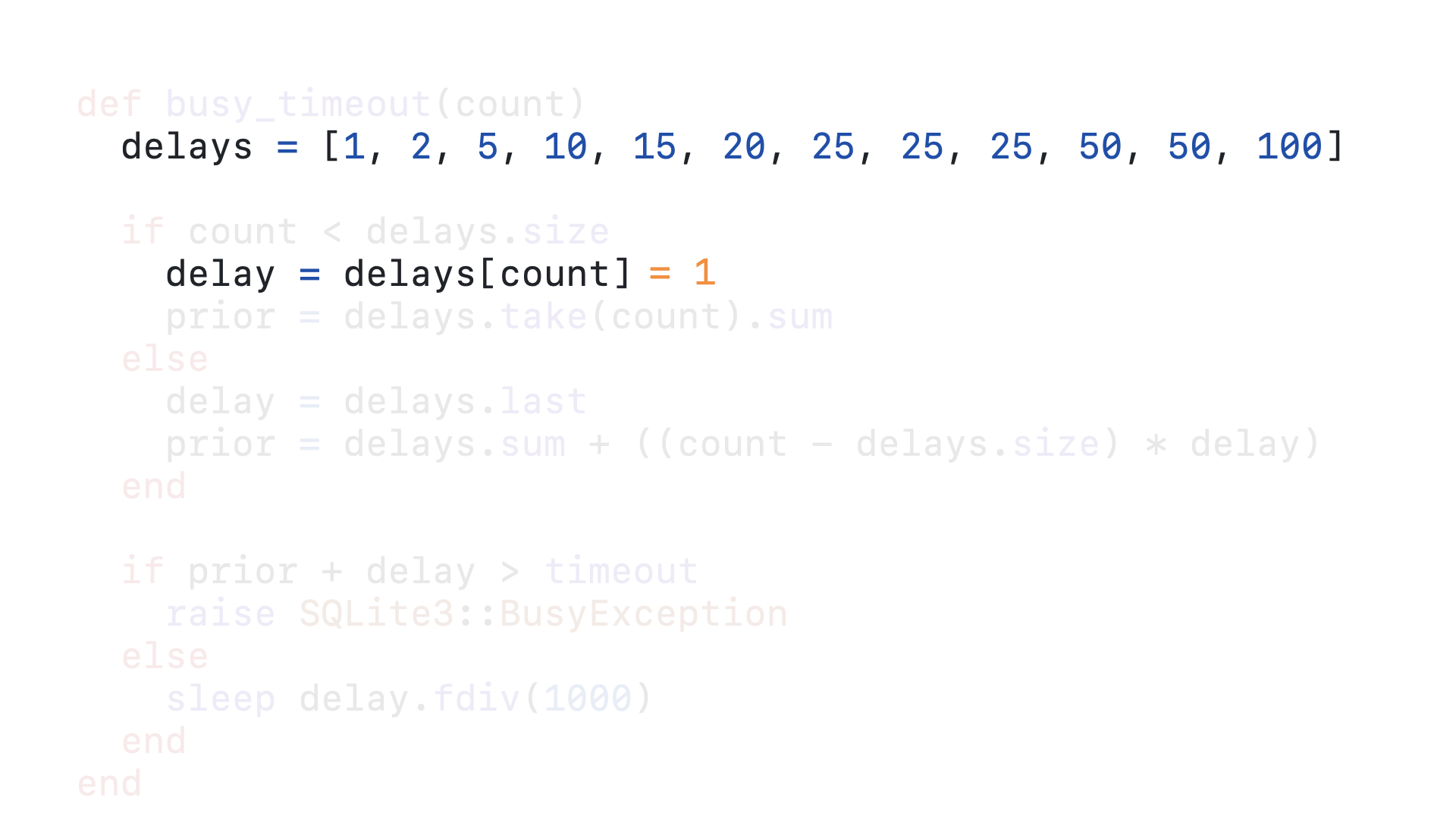

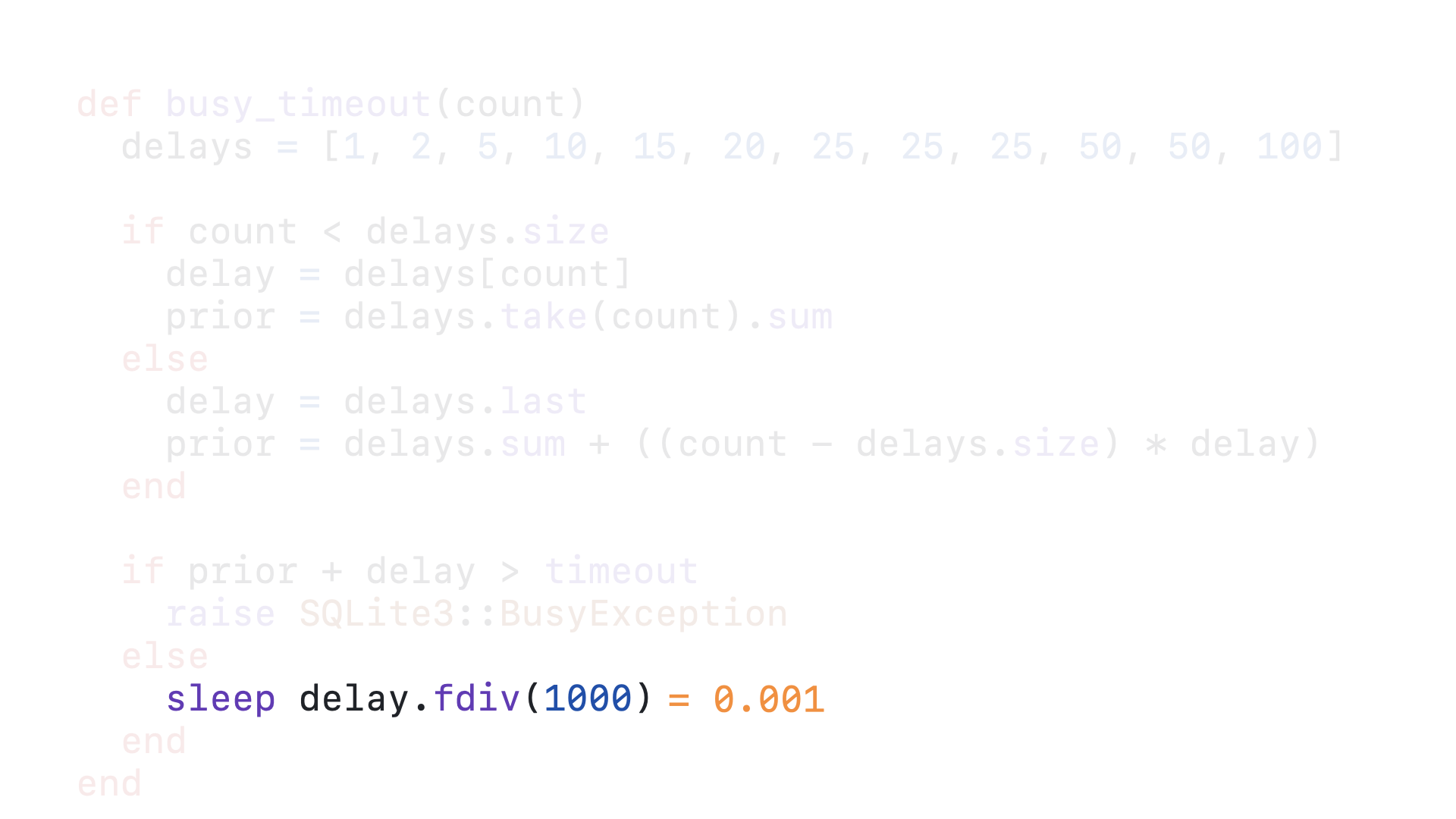

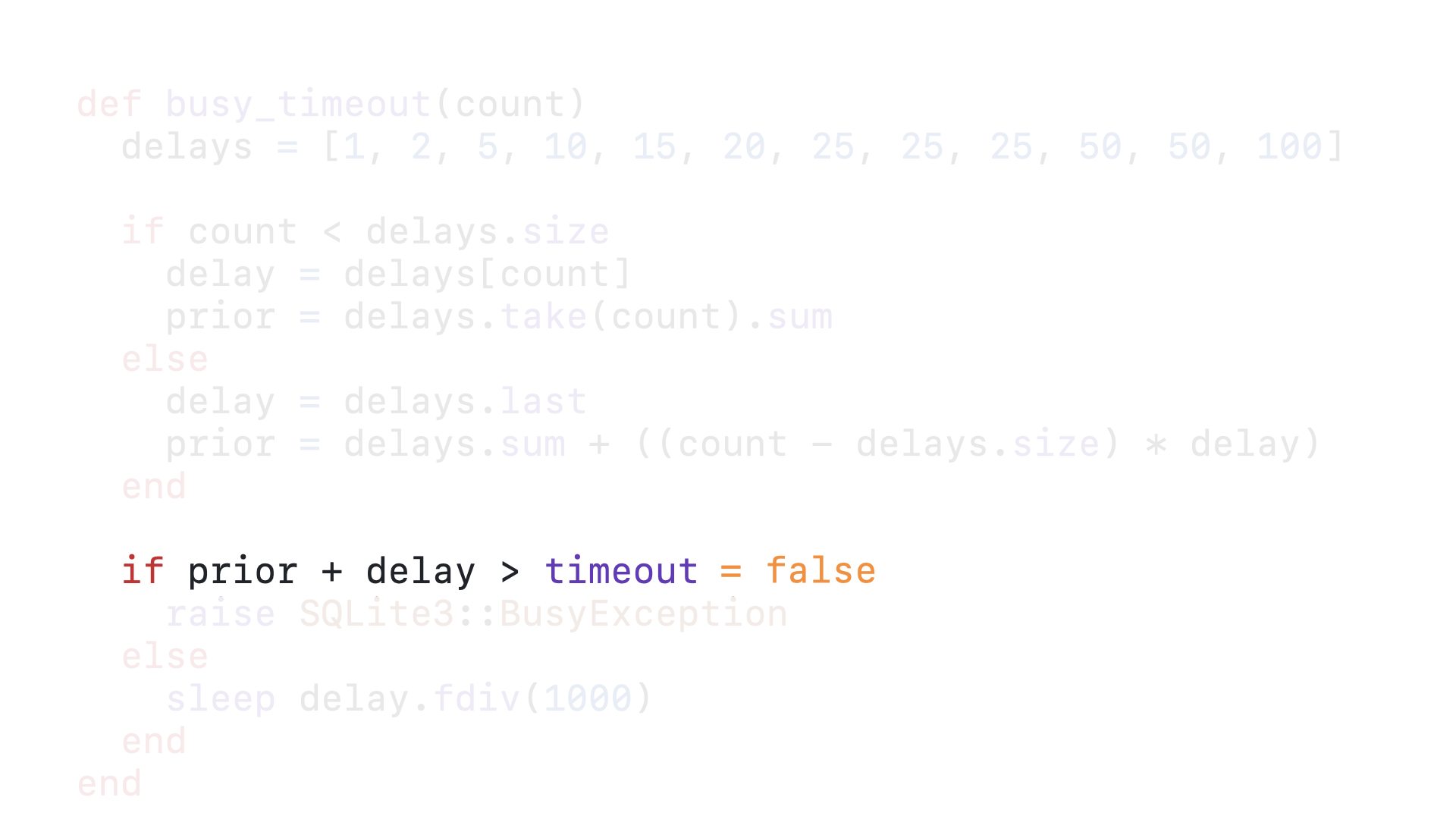

Let’s consider the 58th time this query calls this timeout callback.

58 is greater than 12, so we fall through to the else block.

Once we are past the 12th call to this callback, we will always delay 100 milliseconds.

In order to calculate how long this query has already been delayed, we get the sum of the entire delays array and add the 100 milliseconds times however many times beyond 12 the query has retried. In this case, the sum of the entire delays array is 328, 58 minus 12 is 46 and 46 times 100 is 4600. So 4600 plus 328 is 4928. Up to this point, our query has been delayed for 4928 milliseconds.

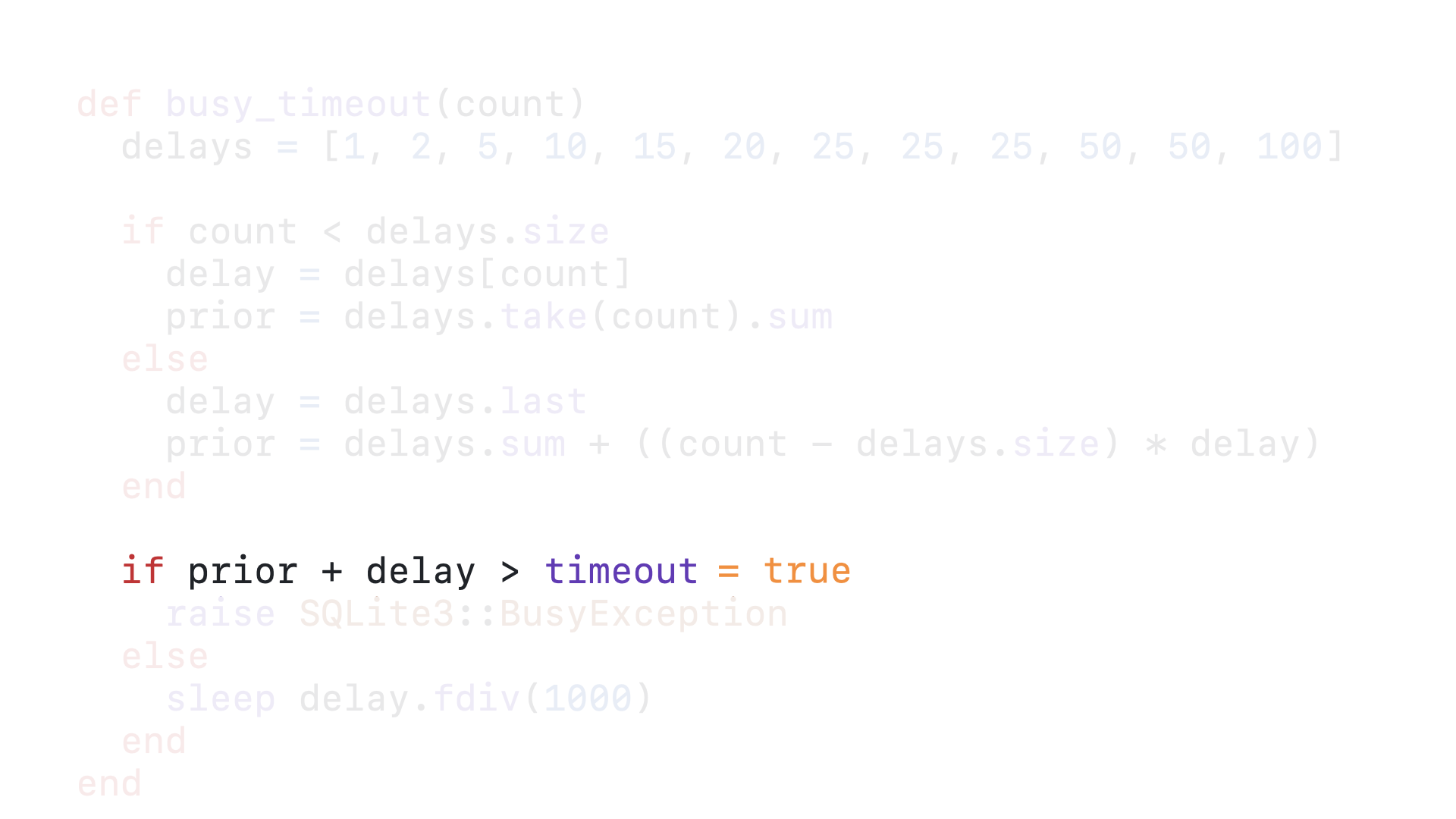

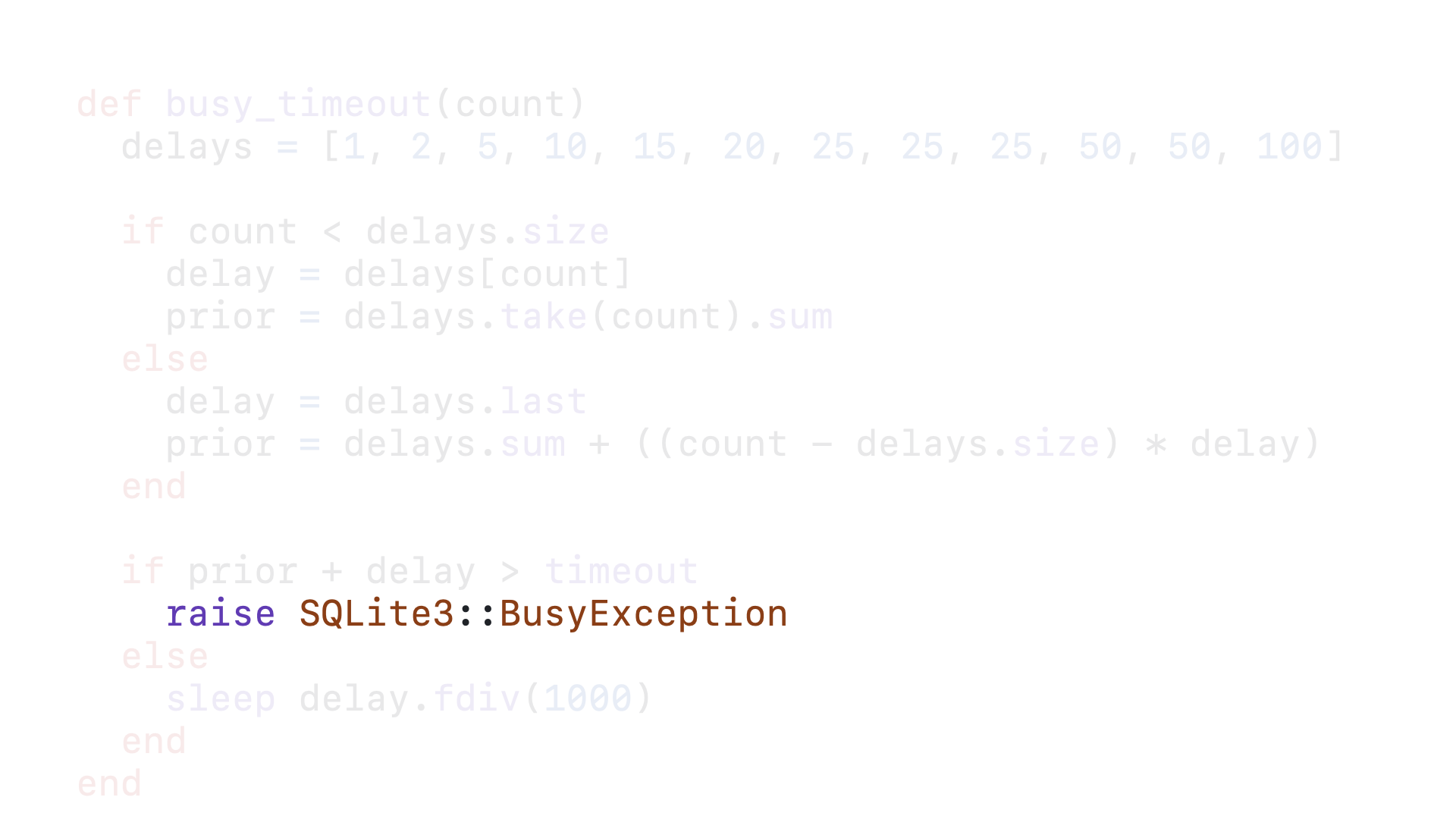

100 + 4928 is 5028, which is indeed greater than 5000, so we enter the if block.

And finally we raise the exception.

I know that stepping through this code might be a bit tedious, but we all need to be on the same page understanding how SQLite’s busy_timeout mechanism handles queued queries. When I say it penalizes old queries, I mean that it makes them much more likely to become timed out queries under consistent load. To understand why, let’s go back to our queued queries…

Let’s track how many retries each query makes from our simple example above.

Our three remaining queries have retried once…

… and now the remaining two queries are, at best, on their second retry.

And our third query is, again at best, on its third retry. On the third retry, the delay is already 10 milliseconds. Let’s imagine that at this moment a new write query is sent to the database.

This new query immediately attempts to acquire the write lock, is denied and makes its zeroth call to the busy_timeout callback. It will be told to wait 1 millisecond. Our original query is waiting for 10 milliseconds, so this new query will get to retry again before our older query.

While the write lock is still held, our new query is only asked to wait 2 milliseconds next.

Even when the count is 2, it is only asked to wait 5 milliseconds. This new query will be allowed to retry to acquire the write lock three times before the original query is allowed to retry once.

These increasing backoffs greatly penalize older queries, such that any query that has to wait even just 3 retries is now much more likely to never acquire the write lock if there is a steady stream of write queries coming in.

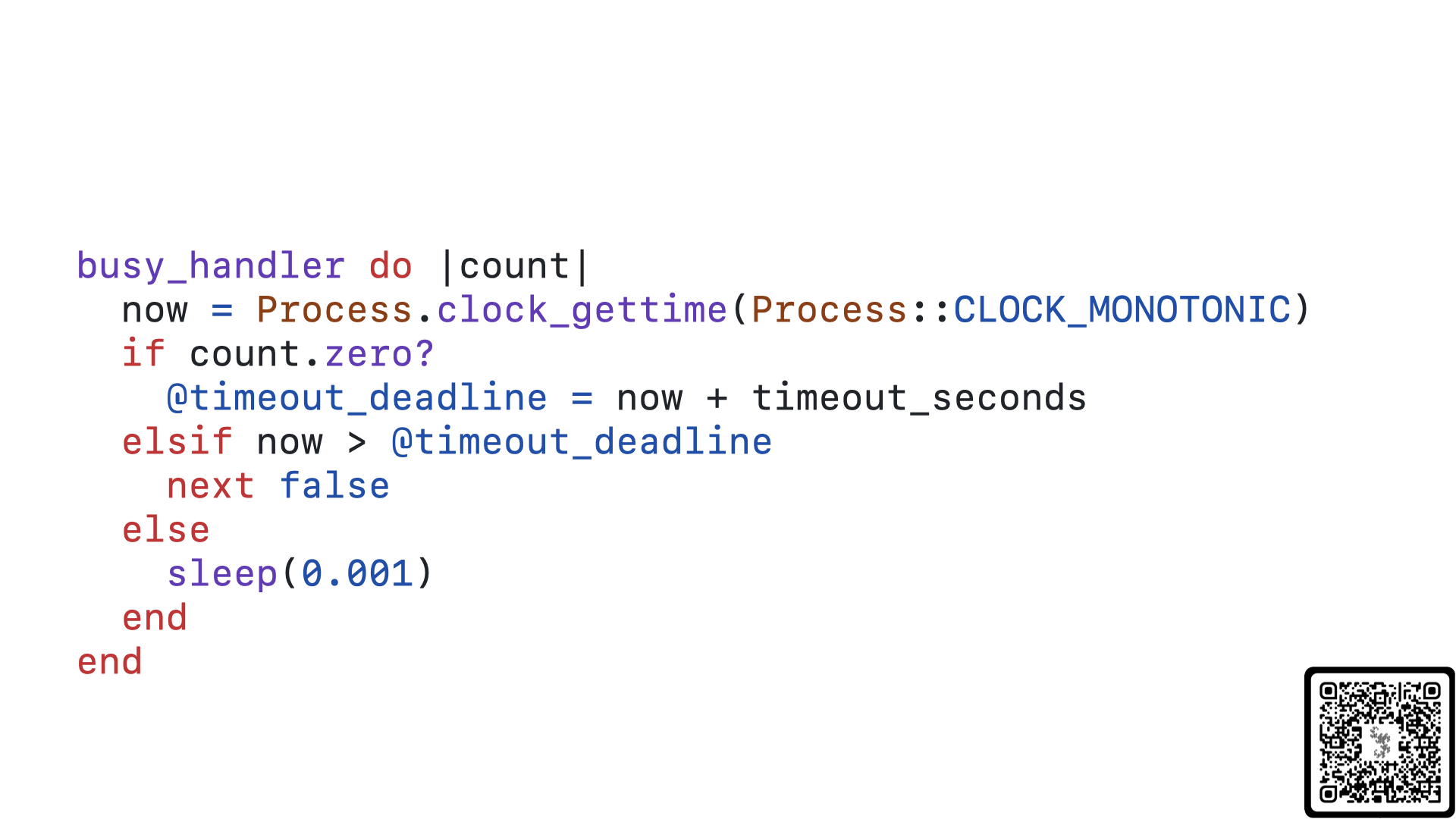

So, what if instead of incrementally backing off our retries, we simply had every query retry at the same frequency, regardless of age? Doing so would also mean that we could do away with our delays array and re-think our busy_handler function altogether.

And that is precisely what we have done in the main branch of the sqlite3-ruby gem. Unfortunately, as of today, this feature is not in a tagged release of the gem, but it should be released relatively soon. This Ruby callback releases the GVL while waiting for a connection using the sleep operation and always sleeps 1 millisecond. These 10 lines of code make a massive difference in the performance of your SQLite on Rails application.

Let’s re-run our benchmarking scripts and see how our p99.99 latency looks now…

Voila! We have flattened out the curve. There is still a jump with currency more than half the number of Puma workers we have, but after that jump our long-tail latency flatlines at around half a second.

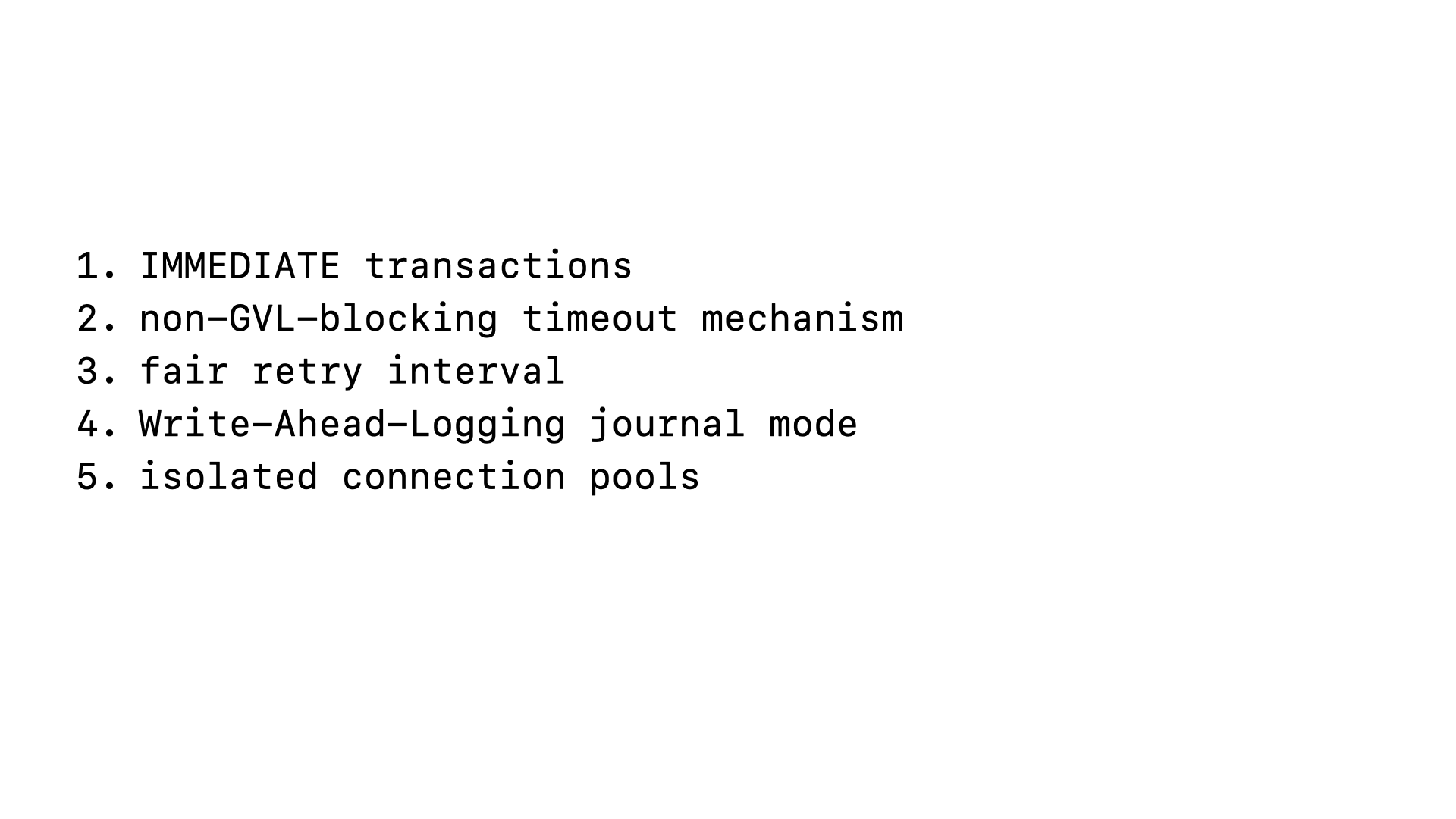

So, when it comes to performance, there are 4 keys that you need to ensure are true of your next SQLite on Rails application…

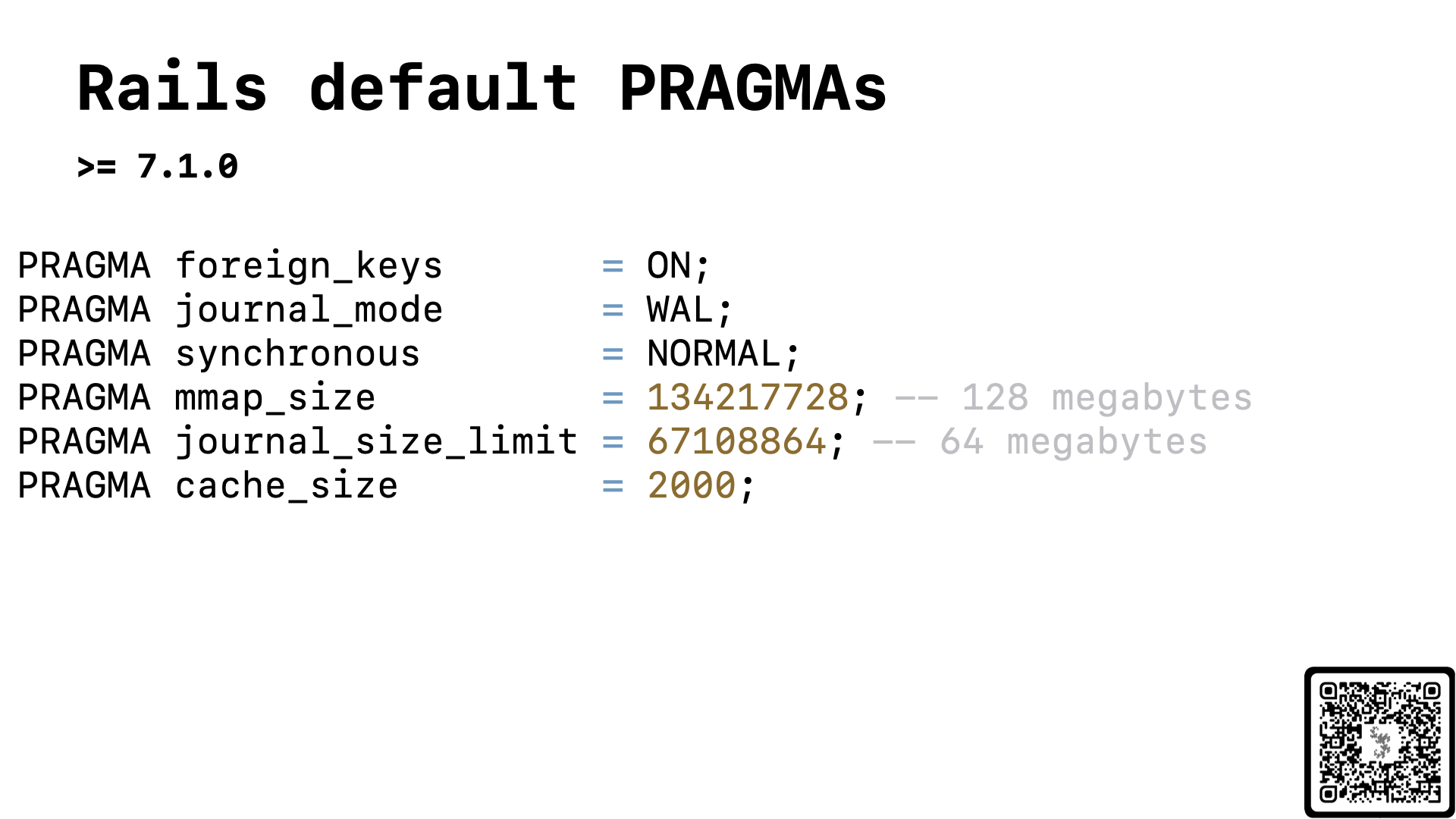

We have covered the first three, but not the last. The write-ahead-log allows SQLite to support multiple concurrent readers. The default rollback journal mode only allows for one query at a time, regardless of whether it is a read or a write. WAL mode allows for concurrent readers but only one writer at a time.

Luckily, starting with Rails 7.1, Rails applies a better default configuration for your SQLite database. These changes are central to making SQLite work well in the context of a web application. If you’d like to learn more about what each of these configuration options are, why we use the values we do, and how this specific collection of configuration details improve things, I have a blog post that digs into these details.

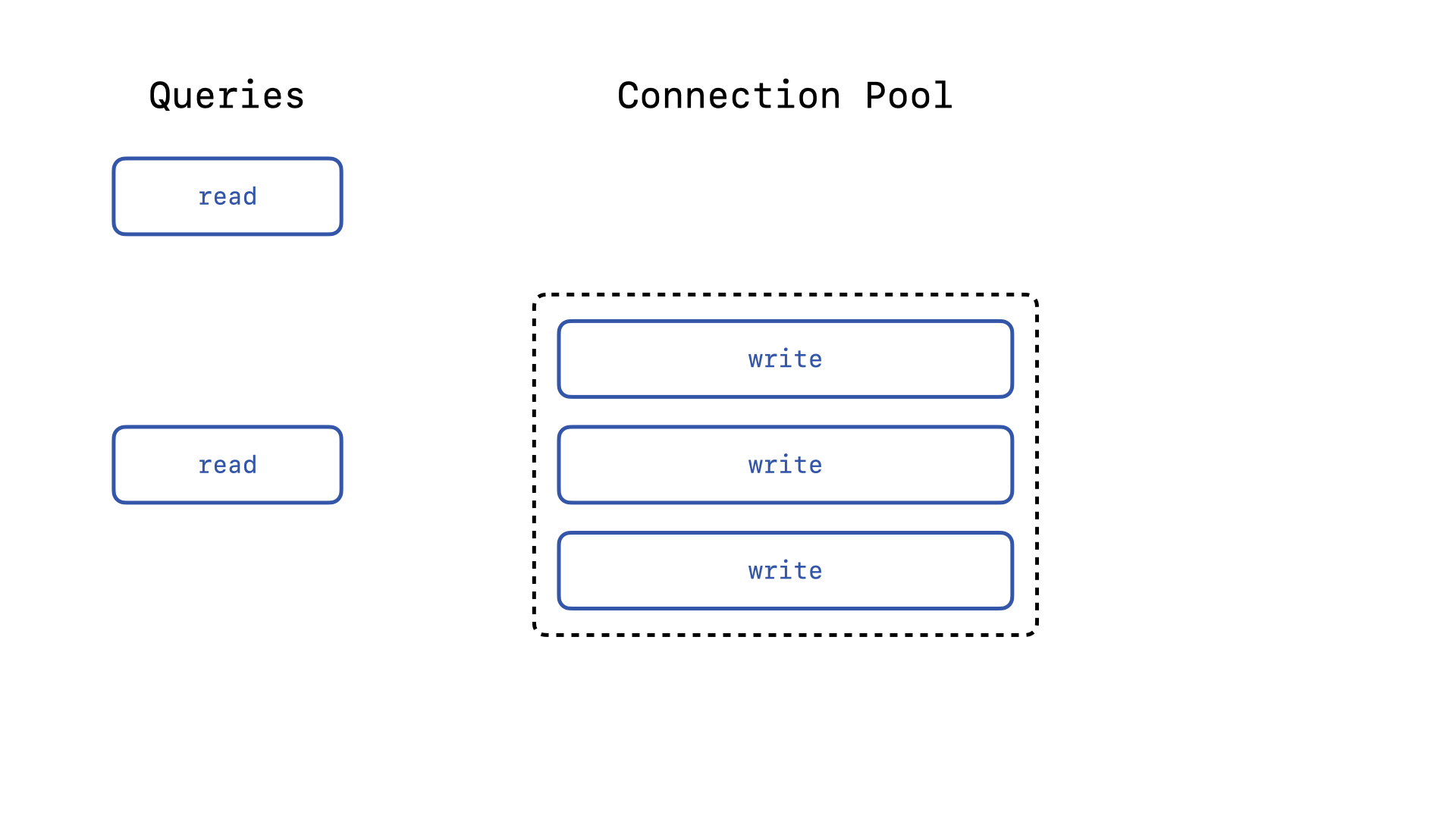

Now, while this isn’t a requirement, there is a fifth lever we can pull to improve the performance of our application. Since we know that SQLite in WAL mode supports multiple concurrent reading connections but only one writing connection at a time, we can recognize that it is possible for the Active Record connection pool to be saturated with writing connections and thus block concurrent reading operations.

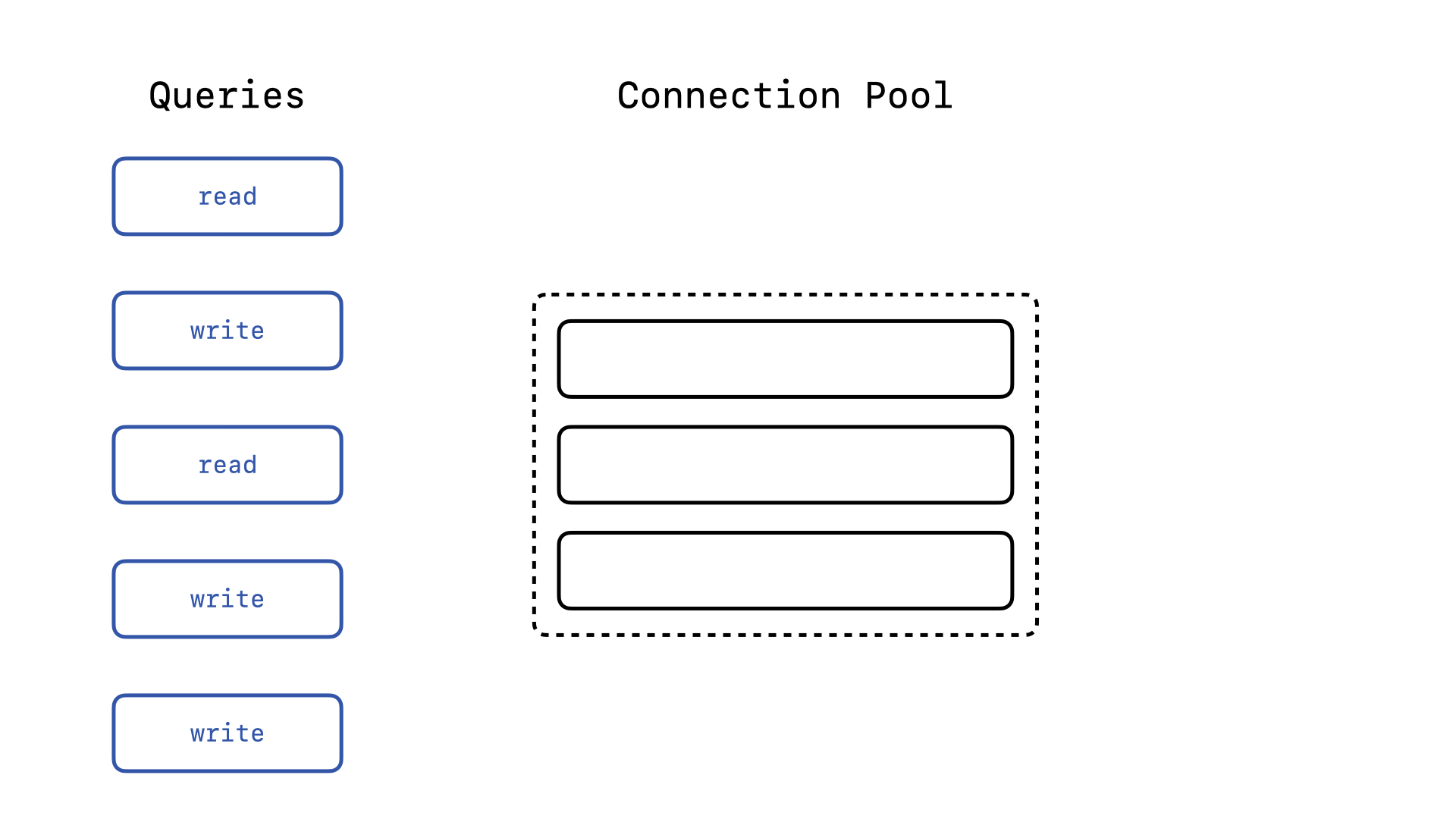

If your connection pool only has 3 connections, and you receive 5 concurrent queries, what happens if the 3 connections get picked up by three write queries?

The remaining read queries have to wait until one of the write queries releases a connection. Ideally, since we are using SQLite in WAL mode, read queries should never need to wait on write queries. In order to ensure this, we will need to create two distinct connection pools—one for reading operation and one for writing operations.

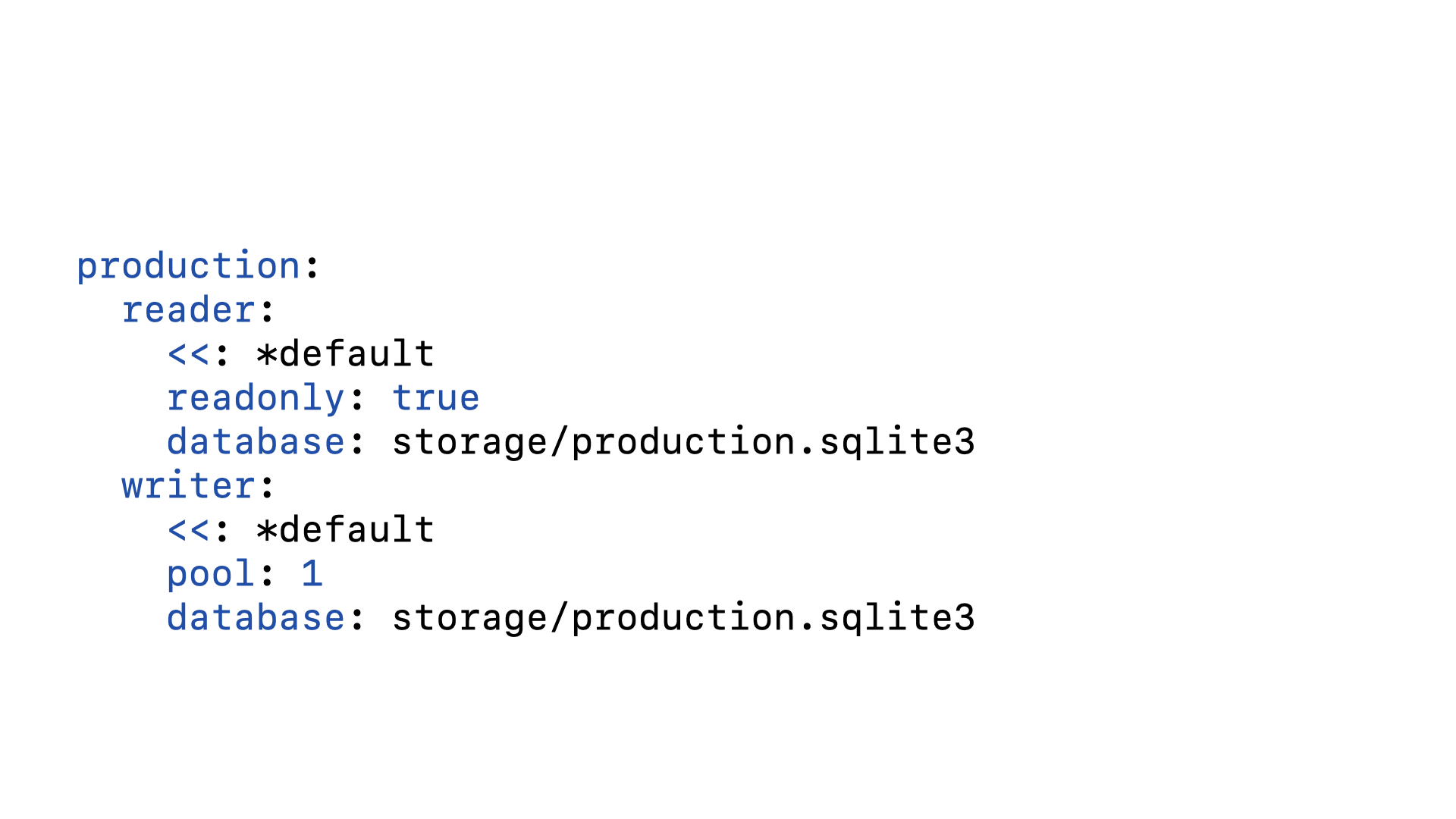

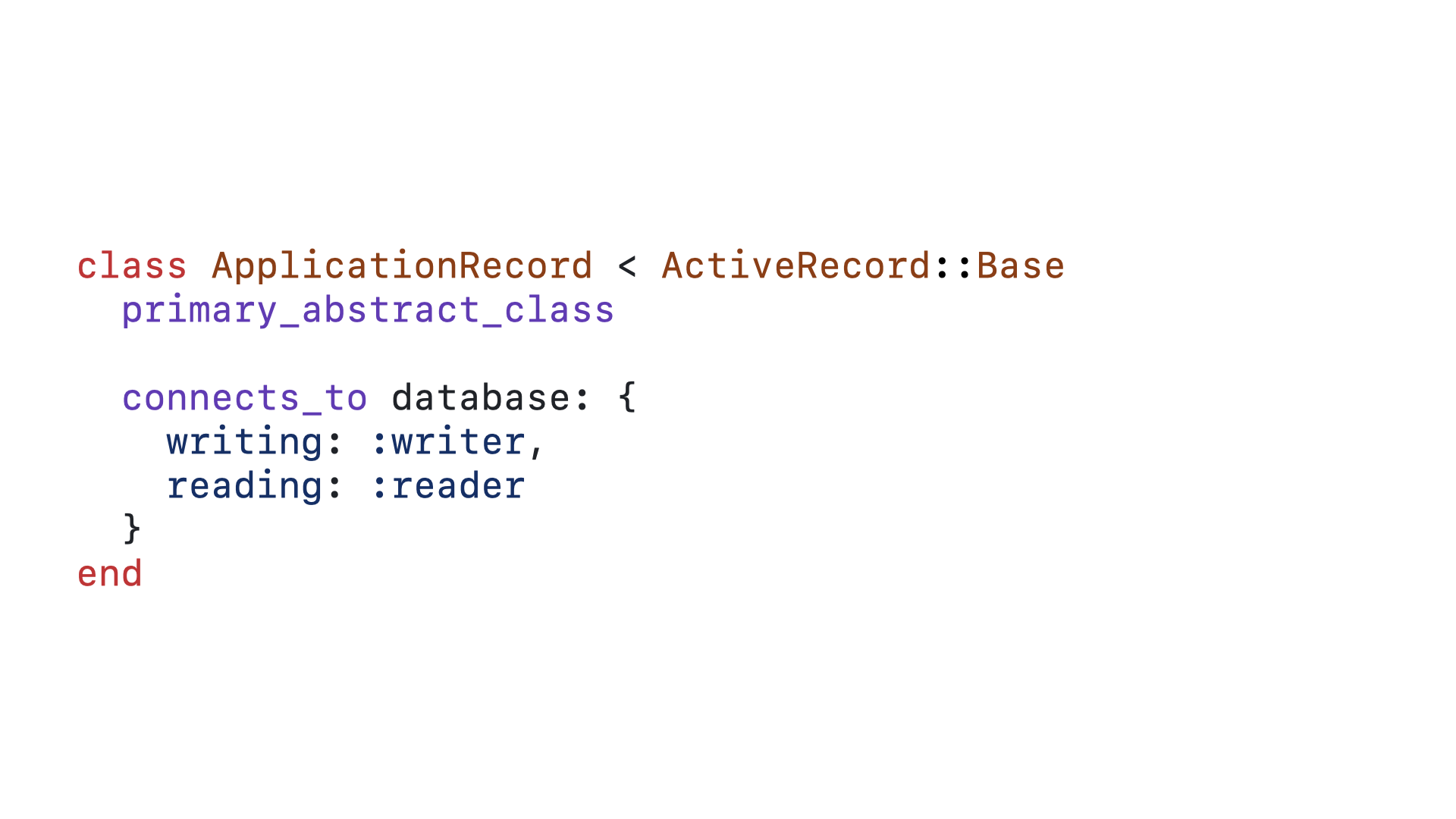

We can leverage Rails’ support for multiple databases to achieve this result. Instead of pointing the reader and writer database configurations to separate databases, we point them at the same single database, and thus simply create two distinct and isolated connection pools with distinct connection configurations.

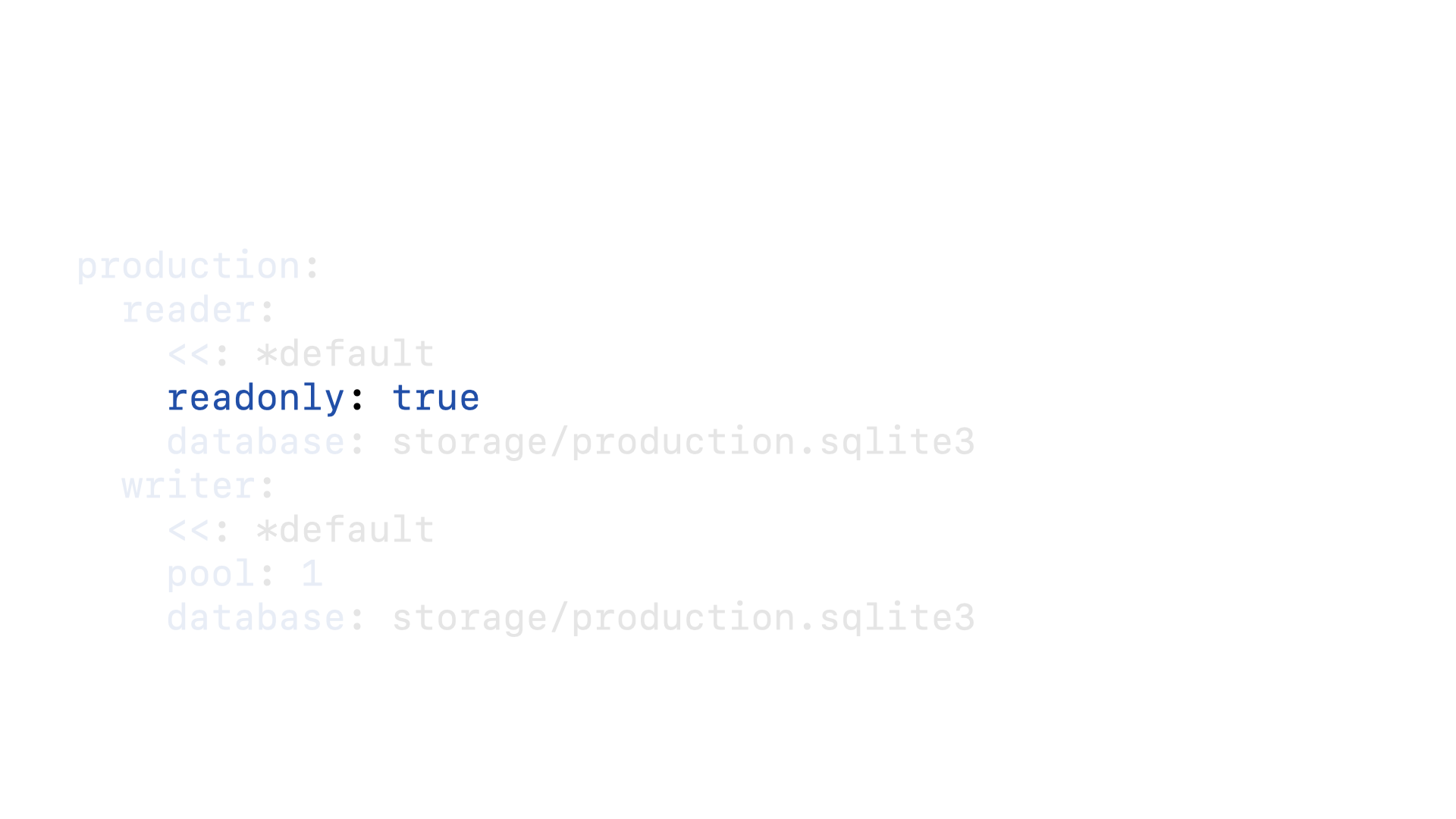

The reader connection pool will only consist of readonly connections…

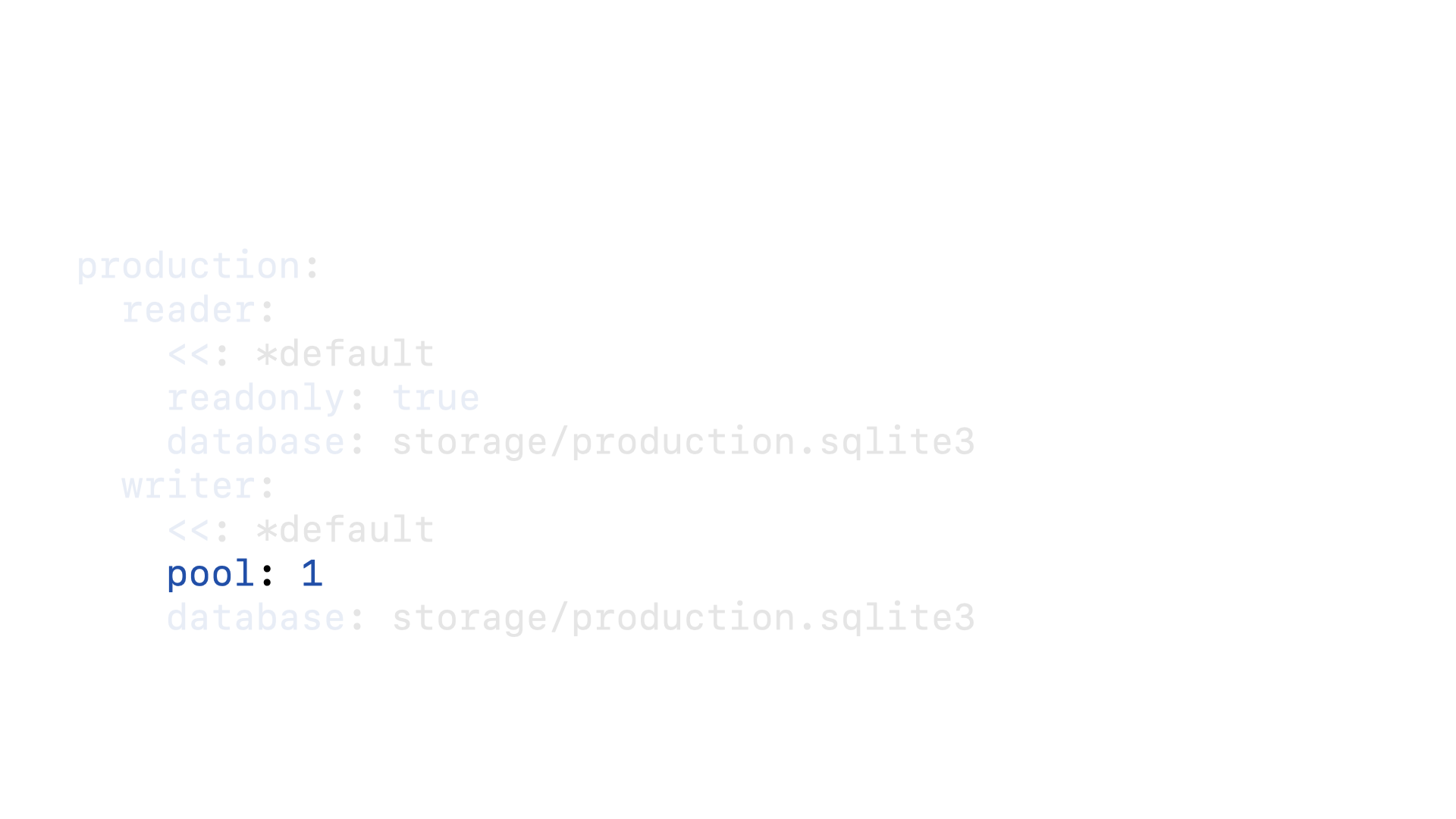

And the writer connection pool will only have one connection.

We can then configure our Active Records models to connect to the appropriate connection pool depending on the role.

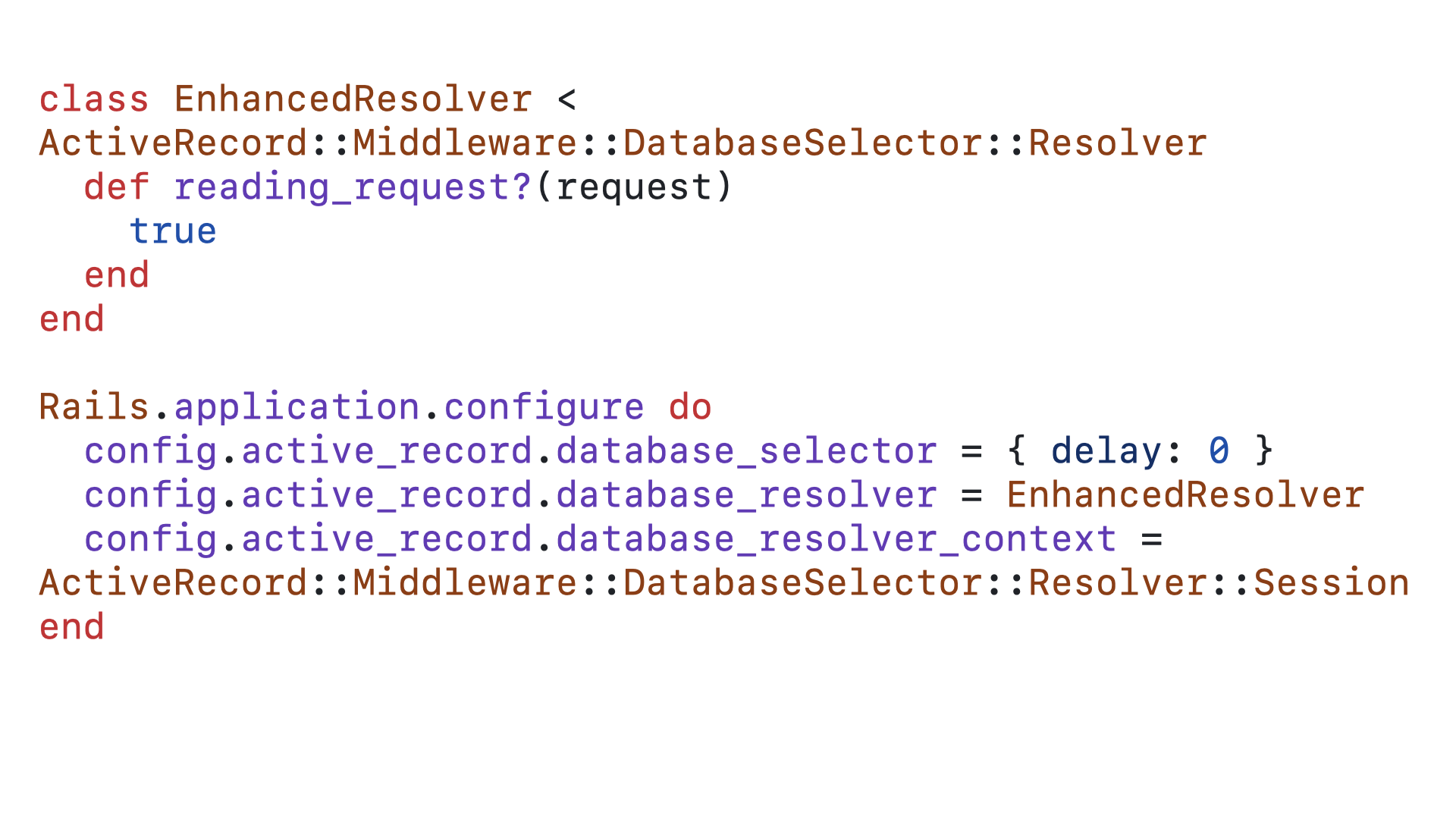

What we want, conceptually, is for our requests to behave essentially like SQLite deferred transactions. Every request should default to using the reader connection pool, but whenever we need to write to the database, we switch to using the writer pool for just that operation. To set that up, we will use Rails’ automatic role switching feature.

By putting this code in an initializer, we will force Rails to set the default database connection for all web requests to be the reading connection pool. We also tweak the delay configuration since we aren’t actually using separate databases, only separate connections, we don’t need to ensure that requests “read your own writes” with a delay.

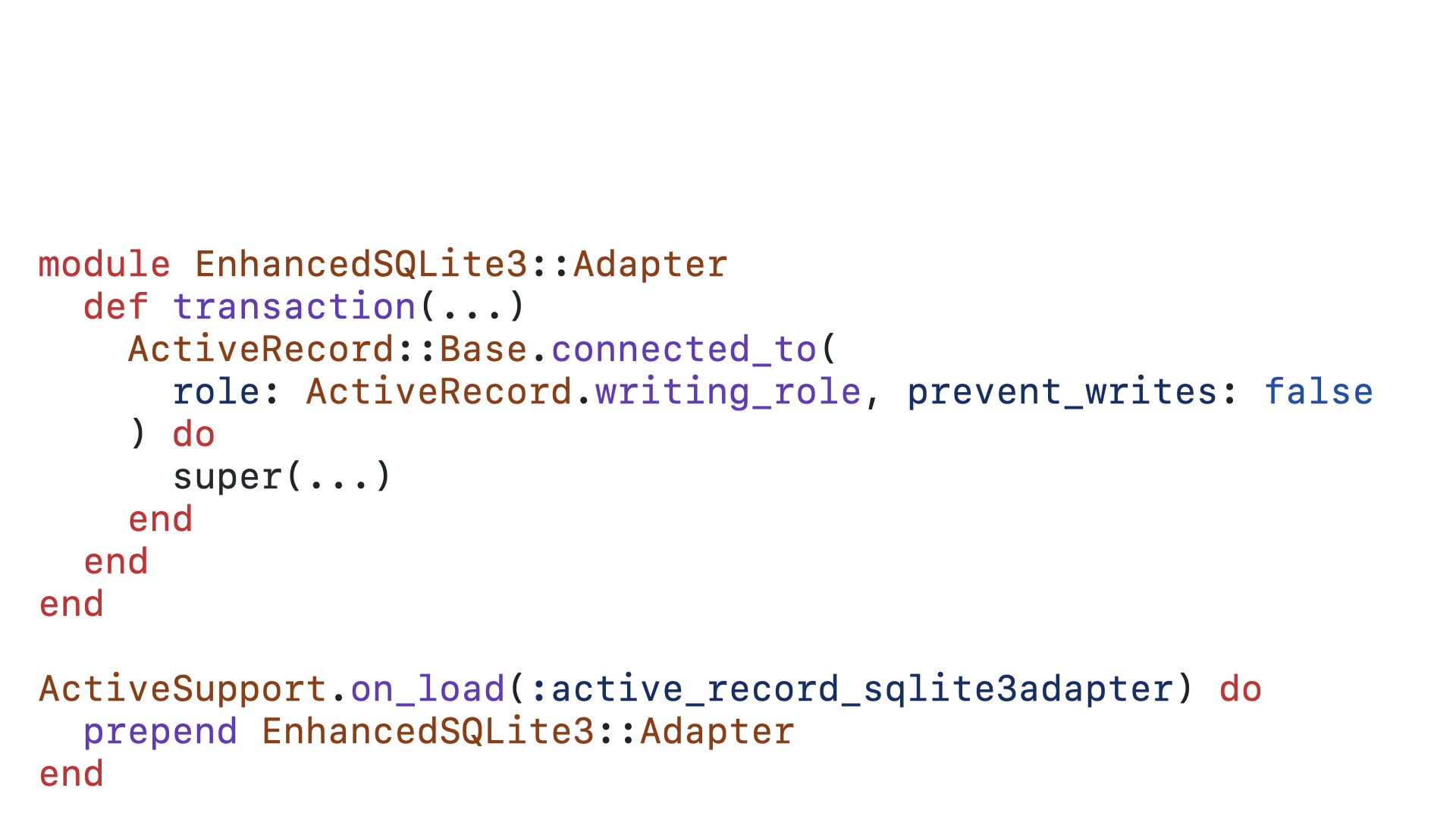

We can then patch the transaction method of the ActiveRecord adapter to force it to connection to the writing database.

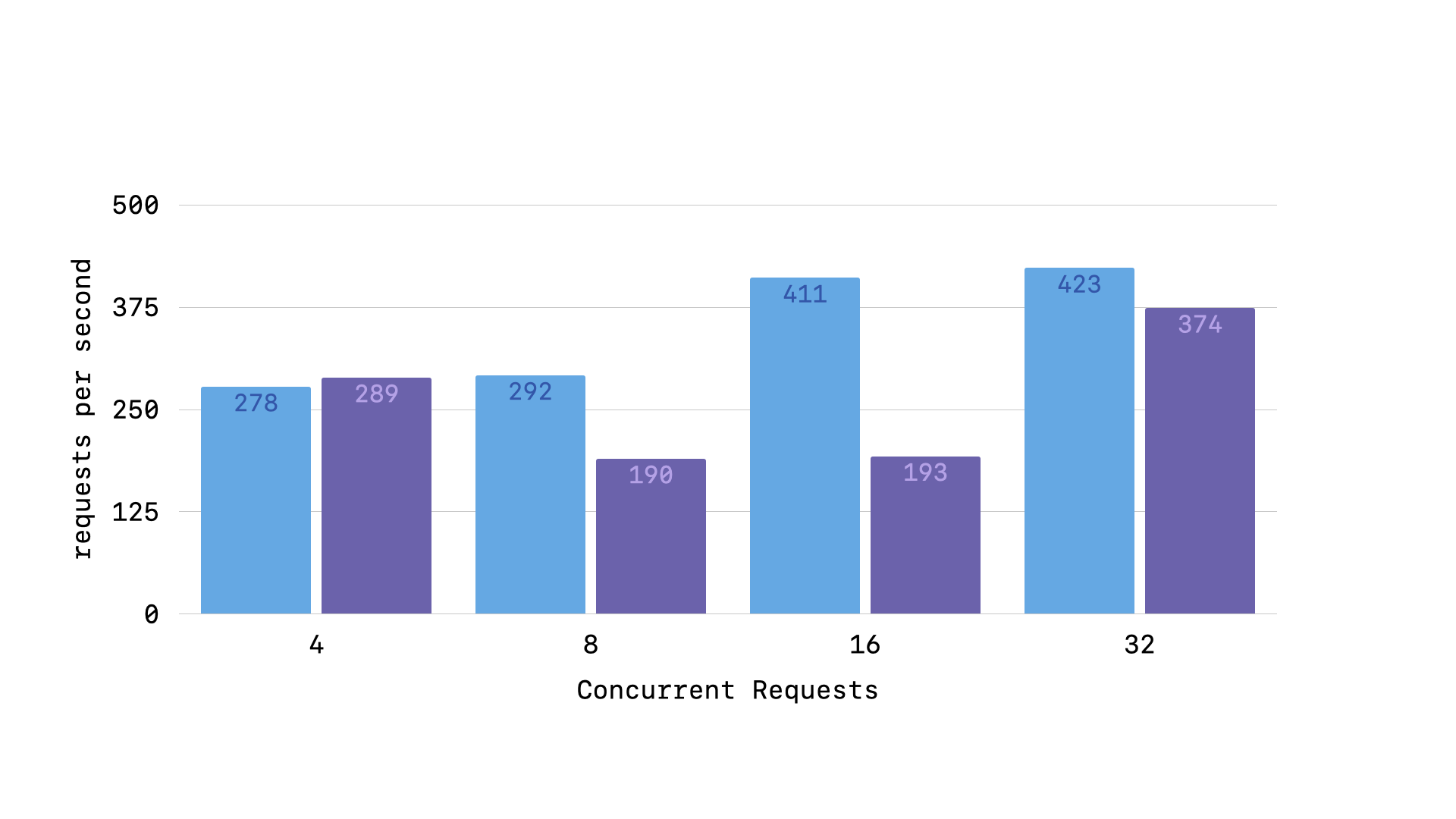

Taken together, these changes enable our “deferred requests” utilizing isolated connection pools. And when testing against the comment create endpoint, we do see a performance improvement when looking at simple requests per second.

So, these are the 5 levels of performance improvement that you should make to your SQLite on Rails application.

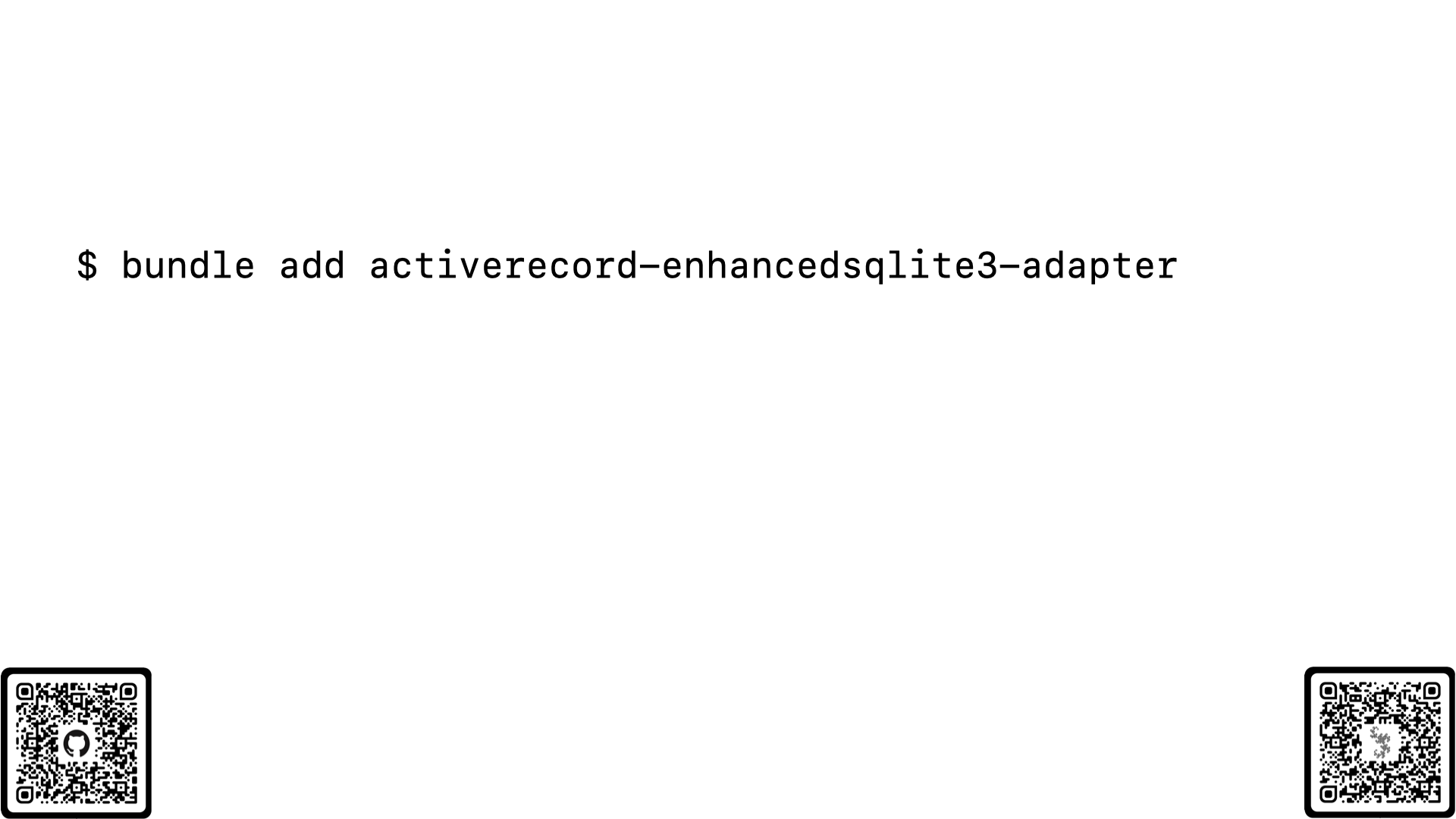

But, you don’t need to walk through all of these enhancements in your Rails app. As I said at the beginning, you can simply install the enhanced adapter gem.

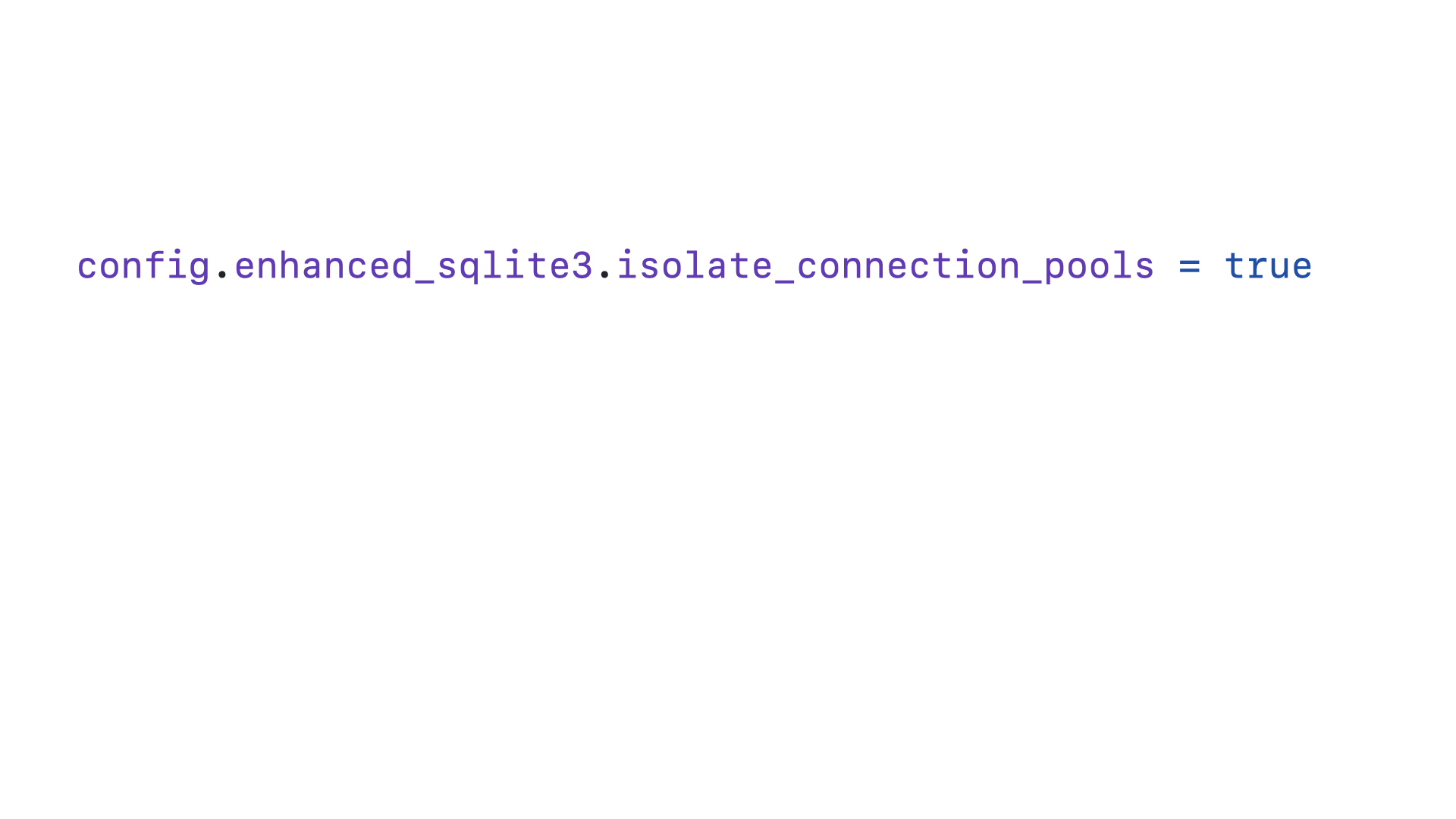

And if you want to use the isolated connection pools, you can simply add this configuration to your application. This is a newer experimental feature, which is why you have to opt into it.

And, after all that, we are now done with how to make your SQLite on Rails application performant.

In the end, I hope that this exploration of the tools, techniques, and defaults for SQLite on Rails applications has shown you how powerful, performant, and flexible this approach is. Rails is legitimately the best web application framework for working with SQLite today. The community’s growing ecosystem of tools and gems is unparalleled. And today is absolutely the right time to start a SQLite on Rails application and explore these things for yourself.

I hope that you now feel confident in the hows (and whys) of optimal performance when running SQLite in production with Rails.

Thank you.