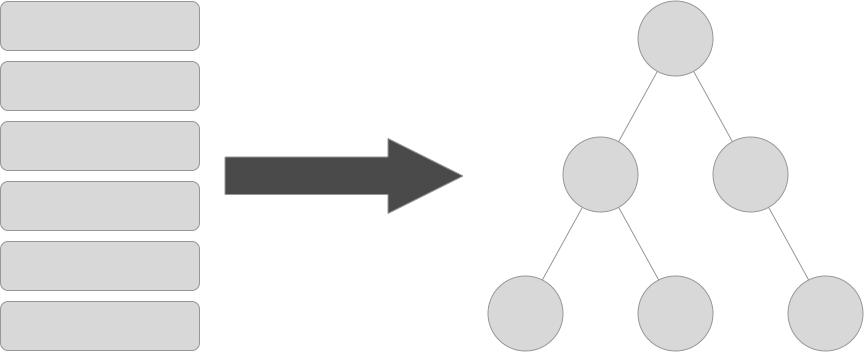

It is, unfortunately, not that often that I get the opportunity to devise an algorithm to solve a problem at work. Most work simply doesn’t require that kind of thinking. But I thoroughly enjoy that kind of thinking, and thus thoroughly enjoyed the most recent opportunity I had to employ it. The problem was simple (though I have simplified and abstracted it for this post as well): we have a database table of things, and these things have a parent-child hierarchy, and we need to display a tree of these things in our UI. So, let’s dig in.

First, let’s examine the basic shape of the database table. Each thing has an id, name, and parent_id, like so:

| id | name | parent_id |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | nil |

| 2 | B | 1 |

| 3 | C | 1 |

| 4 | D | 2 |

| 5 | E | 4 |

| 6 | F | 3 |

| 7 | G | nil |

Each row in the table gives us a “node” for our tree and tells us about that node’s parent. This means that we cannot know by looking at a single row whether or not that “node” will have any children, but we can know if that “node” has a parent and what other “node” that parent is. If we want to think of this data in Ruby, this would be an array of hashes:

[ {id: 1, name: 'A', parent_id: nil}, {id: 2, name: 'B', parent_id: 1}, {id: 3, name: 'C', parent_id: 1}, {id: 4, name: 'D', parent_id: 2}, {id: 5, name: 'E', parent_id: 4}, {id: 6, name: 'F', parent_id: 3}, {id: 7, name: 'G', parent_id: nil}]That is the shape of the data that we are starting with, but what is the shape of the data that we want? We want a nested tree in the UI, so I think that is best represented in Ruby as a nested hash:

{ 1: { name: 'A', children: { 2: { name: 'B', children: { 4: { name: 'D', children: { 5: { name: 'E' } } } } }, 3: { name: 'C', children: { 6: { name: 'F' } } }, } }, 7: { name: 'G' }}We now know where we are coming from and where we are going; the only thing left to do is to get there.

I like to start with simple facts, things that I know to be true. For example, if we are starting with an array of hashes, our solution is going to need to iterate over that array. It is also a fact that any “node” in the tree can be described as one of three things: a “root”, a “leaf”, or a “branch”. Here I may be stretching the tree metaphor a bit too far, but bear with me.

- A “root” is a top level object; it has children but no parent.

- A “leaf” is the exact opposite; it has a parent but no children.

- A “branch”, then, is simply a node that has both a parent and children.

Now, we said earlier that we cannot know by looking at a simple node whether or not it has children. This means that we cannot determine if a particular node is a “branch” or a “leaf” just by examining it. We can, however, determine if a particular node is a “root” or not on its own.

A final thing that we know is that an efficient algorithm to solve this problem will only scan the initial array once. We want to iterate over that array of hashes once and build up our nested hash as we go.

We have some basic facts before us so let’s start actually trying to write some code. We need to iterate over the array of hashes, so let’s start there:

# `nodes` = the array of hashesnodes.each do |node| # some computationendWe also know that we want to get a hash out at the end, and that we will need to build that hash as we iterate over the array, so let’s initialize that hash as well:

tree = {}# `nodes` = the array of hashesnodes.each do |node| # some computationendWe know that as we iterate over the nodes, we need to insert each node into the tree. Let’s start with a naive implementation:

tree = {}# `nodes` = the array of hashesnodes.each do |node| tree[node[:id]] = node.reject { |k, v| k == :id }endI call this “naive” not to be condescending; it is literally where I started and I think it is a healthy place to start. Iteration is at the heart of good programming, good thinking. We know where we are going but not how quite to get there, so let’s experiment and learn as we go. Here, we start to learn something important. For, while this will turn an array of hashes into a single hash, it gets us nowhere near a nested hash. If we were to run this code, we would simply get:

{ 1 => { name: 'A', parent_id: nil}, 2 => { name: 'B', parent_id: 1}, 3 => { name: 'C', parent_id: 1}, 4 => { name: 'D', parent_id: 2}, 5 => { name: 'E', parent_id: 4}, 6 => { name: 'F', parent_id: 3}, 7 => { name: 'G', parent_id: nil}}Our array is now a hash, but the basic shape of the data hasn’t changed at all. Moreover, this naive approach has shown us that we really need to do something with the parent_id of each node as we process it. Also, I notice a key difference between our starting data and our desired output data: our starting data focuses on the “parent” of the “parent-child” relationship (via parent_id), while our output data focuses on the “child” (with the children key). Making this switch will prove to be difficult, but let’s examine why.

We said earlier that we can tell by looking at a single node whether or not it is a “root” or not, that is, whether or not it has a parent. This means we could build the first level of our nested hash quite simply:

tree = {}# `nodes` = the array of hashesnodes.each do |node| tree[node[:id]] = node.reject { |k, v| k.to_s.include? 'id' } if node[:parent_id] == nilendThis would produce a tree with this shape:

{ 1 => { name: "A" }, 7 => { name: "G" }}This, at least, is starting to look like our desired output. But what do we do about the possible children? We don’t know if either of these nodes has children just by looking at them; we only that a node is a child if it has a parent_id. So this switch from a parent-centric perspective to a children-centric perspective is going to be difficult. In fact, spoiler warning, if we want to get the nested hash output we described initially and only parse the array once, we are screwed. We are screwed because we can’t insert a node into an arbitrary place in the nested hash.

We could create an auto-vivifying hash and insert a node arbitrarily deep in the hash:

autovivifying_tree = Hash.new { |h, k| h[k] = Hash.new(&h.default_proc) }autovivifying_tree.dig(1, 2, 4, 5)# autovivifying_tree => {1=>{2=>{4=>{5=>{}}}}}The problem here is that we have to have the path to the nested node; we need to know that nodes ancestors. But, in our data, we can only learn the ancestor paths by parsing the whole array. This data model also fails to give us the name of each node. So, what to do?

At this point, I determined that the nested hash was simply going to be impossible to create by parsing the array once. Moreover, I realized that it was not necessary (or even most effective) for storing the data in the way my UI would need it. While a nested hash most directly modeled the shape of the data I needed, the directness of the model comes at the expense of efficiency and ease of use. An arbitrarily nested hash is more difficult for the UI code to parse. It would need a recursive function, which would need to check if the hash under consideration had a children key, and would have to traverse the whole tree without knowing the keys (a central benefit of Hashes as a data structure). Thus, while visually the closest to a “tree”, the nested hash comes with too much baggage for our implementation. So let’s go back to the drawing board for what our output data structure could and should look like.

As I turned myself back to the problem, I thought about what kind of code I would like in my UI to generate the visual tree. I would like to efficiently navigate the entire collection of things, moving from the top of the hierarchy (things with no parent, i.e. “roots”) thru the various middle layers (the “branches”) and down to the very bottom (the “leaves”). I want this parsing to be as direct and efficient as the parsing of the database–one pass. When you want to navigate data directly and effienctly, Hashes are a great place to start. But, we have already discussed the difficulties with a nested hash, so let’s use a flat hash. The keys should be the id of the thing, one entry per row in the database. The values need to tell use at least two pieces of information: the parent and the children of that particular thing. That is, we want something that would look like this:

{ nil => { children: [1, 7] }, 1 => { name: 'A', parent_id: nil, children: [2, 3] }, 2 => { name: 'B', parent_id: 1, children: [4] }, 3 => { name: 'C', parent_id: 1, children: [6] }, 4 => { name: 'D', parent_id: 2, children: [5] }, 5 => { name: 'E', parent_id: 4, children: [] }, 6 => { name: 'F', parent_id: 3, children: [] }, 7 => { name: 'G', parent_id: nil, children: [] }}We could navigate this data structure hierarchically with ease.

visit_children = ->(node, tree) do children = tree[node][:children] content_tag(:li) do content_tag(:span, tree[node][:name]) + (content_tag(:ul) do safe_join(children.map do |child| visit_children.call(child, tree) end) end) if children endend roots = tree[nil][:children]content_tag(:ul) do roots.each { |root| visit_children.call(root, tree) }endThis code would create this HTML:

<ul> <li> <span>A</span> <ul> <li> <span>B</span> <ul> <li> <span>D</span> <ul> <li><span>E</span></li> </ul> </li> </ul> </li> <li> <span>C</span> <ul> <li><span>F</span></li> </ul> </li> </ul> </li> <li><span>G</span></li></ul>Our front-end code suggests to use that this data structure would work well for our needs. So, now all we need to do is munge our array of hashes into a hash of the structure described.

Let’s think through what precisely we need to happen. We need to iterate over an array of hashes. For each item/node/hash in that array, we need to store a reference in the tree. For each node we also need to add that node to its parent reference in the tree. This means we need to ensure that the reference to the parent already exists in the tree; that is, imagine a scenario where we process node 2 before node 1 (the parent of node 2). We cannot add node 2 to node 1’s children if node 1 does not exist in the tree. This, however, should be sufficient for parsing our array of hashes into a hash of nodes to be consumed by our UI code. So, let’s start building it!

We already know we must start with a tree and iterating of the nodes:

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| # ...endNow, we also need to either find or create the reference to the node in the tree:

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| tree[node[:id]] ||= {}endThe ||= operator is what allows us to “find or create” a reference in the tree hash. If tree[node[:id]] already has a value, nothing happens; but, if it doesn’t, the value is set to the empty hash {}.

But we don’t just want an empty hash for the value in the tree; we want to set the parent_id and initialize the children array (plus insert the name):

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| tree[node[:id]] ||= { parent_id: node[:parent_id], children: [], name: node[:name] }endIf we were to process nodes with just this code, at the end tree would look like this:

{ 1 => { parent_id: nil, children: [], name: "A" }, 2 => { parent_id: 1, children: [], name: "B" }, 3 => { parent_id: 1, children: [], name: "C" }, 4 => { parent_id: 2, children: [], name: "D" }, 5 => { parent_id: 4, children: [], name: "E" }, 6 => { parent_id: 3, children: [], name: "F" }, 7 => { parent_id: nil, children: [], name: "G" }}We are close. All we need to do now is fill in the children information. A first step would be to mimic what we do with node[:id] in dealing with node[:parent_id], that is, “find or create” its reference in the tree:

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| tree[node[:id]] ||= { parent_id: node[:parent_id], children: [], name: node[:name] } tree[node[:parent_id]] ||= { parent_id: nil, children: [node[:id]], name: nil }endThis has a hole, however, in its logic. Every node in tree will only ever have the shape it was initialized with. This means that if we visit node 2 first, node 2’s children array will never be updated to include node 4 and node 1’s reference will never have any more chilren than node 2, never have a name, and never have a parent_id (the logic still holds even if, in this particular scenario, node 1’s parent is nil). So, we need a way to update references when we gather new information (on subsequent iterations). The first thing we must do is ensure that we set parent_id and name for every node as we process it, whether that node has a reference in the tree yet or not:

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| default = { parent_id: node[:parent_id], children: [], name: node[:name] } tree[node[:id]] ||= default tree[node[:id]] = tree[node[:id]].merge(default) tree[node[:parent_id]] ||= { parent_id: nil, children: [node[:id]], name: nil }endThis code ensures that tree[node[:id]] always has the proper parent_id and name. Unfortunately, however, it also obliterates any children value that may have been previously set. So, let’s remove children from our reference default:

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| default = { parent_id: node[:parent_id], name: node[:name] } tree[node[:id]] ||= default tree[node[:id]] = tree[node[:id]].merge(default) tree[node[:parent_id]] ||= { parent_id: nil, children: [node[:id]], name: nil }endThis now at least ensures that if I visit a parent node after I have visited one of its children, the parent’s children array will still be intact. It does not, however, ensure that the children array is properly updated. Recall that in our test data node 1 has two children (2 and 3). This code will never give us a reference node with more than one item in the children array. Moreover, it doesn’t help us, when I visit a parent node first and one of its children later, to ensure that the reference to the parent node is updated while processing the child node to have that child node in its children array. What we need is to treat the parent node as intelligently as the current node on each processing cycle:

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| current_default = { parent_id: node[:parent_id], name: node[:name] } tree[node[:id]] ||= current_default tree[node[:id]] = tree[node[:id]].merge(current_default) parent_default = { children: [] } tree[node[:parent_id]] ||= parent_default tree[node[:parent_id]] = parent_default.merge(tree[node[:parent_id]]) tree[node[:parent_id]][:children].push(node[:id])endThis code can now handle multiple children and cares not for which node (parent or child) we visit first. This code, when processing our array of nodes, would produce:

{ nil => { children: [1, 7] }, 1 => { name: 'A', parent_id: nil, children: [2, 3] }, 2 => { name: 'B', parent_id: 1, children: [4] }, 3 => { name: 'C', parent_id: 1, children: [6] }, 4 => { name: 'D', parent_id: 2, children: [5] }, 5 => { name: 'E', parent_id: 4, children: [] }, 6 => { name: 'F', parent_id: 3, children: [] }, 7 => { name: 'G', parent_id: nil, children: [] }}Huzzah! This is what we have been looking for! Pat yourself on the back, we’ve finally made our way to our goal. I hope this long (and sometimes circuitous) journey has helped you. I’ve tried to walk through the ups and downs, the missteps and recalibrations, that my actual process resembled. I have also tried to write code that is readable and understandable before all else. This code, however, is not the code that I actually ended up with or used. I used a few more elegant Ruby-isms to accomplish my goal. So, I leave you with my actual implementation, without a walk-thru, as a bit of mental homework. If you can understand how and why this code accomplishes the same goals as the above code, you will have learned a good deal about Ruby. And, I promise to write up an explanation at some point as well ;)

tree = {}nodes.each do |node| current = tree.fetch(node[:id]) { |key| tree[key] = {} } parent = tree.fetch(node[:parent_id]) { |key| tree[key] = {} } siblings = parent.fetch(:children) { |key| parent[key] = [] } current[:parent] = node[:parent_id] siblings.push(node[:id])end