Epistemology has fascinated me far longer than I have known what that word means. Built upon the Greek words for “knowledge” (ἐπιστήμη) and “study” (λόγος), epistemology means the study of knowledge. This can (and does) encompass a wide variety of specific ideas: the nature of knowledge, the acquisition of knowledge, the difference between knowledge and opinion, etc. It is a field of inquiry that aims to help us answer questions like “How do I know something?”, “What does it mean to know something?”, “Are some things unknowable?”, etc. Now, before we go too far down this (admittedly intriguing) rabbit-hole, I had said that I wanted to consider alethiology, not epistemology. While epistemology is the study of knowledge, alethiology is the study of truth. The two inquiries are cousins; indeed, one can barely call alethiology a field of inquiry 1 and is often considered a sub-field of epistemology. The standard definition of knowledge holds that knowledge equals justified true belief 2. In debating the finer points of that definition, academics must then define their terms. What does it mean for a belief to be justified? What does it mean for a belief to be true? What is truth? This context is, I believe, important as it helps to situate the kinds of questions I am interested in pursuing within their general philosophical context. I want to probe around the edges of the question “What is truth?”, which, as we see, has strong implications on the nature of knowledge.

A Primer on Propositional Logic #

When considering the nature of truth, it is common to think about propositions. Propositions are simply declarative sentences; they are statements. In most high school English courses we learn that sentences that end with a period (.) are declarative sentences (? = interrogatives, ! = interjections). So, that previous sentence was a declarative sentence. So was that one! Ah, now we have an interjection. Well, I could play this game all night (really, I’m easily amused), but the point ought to be clear: propositions == statements == declarative sentences. They are forms of communication that say something is the case. A key characteristic of propositions is that they are either true or false. When I state that something is the case, it either is the case or it isn’t. Either most high school English classes do teach that sentences ending in a period are declarative sentences, or they don’t. Either that previous sentence is a declarative sentence, or it isn’t. Now, one important thing to note immediately is that we need not be able to determine whether a proposition is true or false; this has no bearing on its “propositionness”. The statement “God exists” is a proposition, it is either true or false; however, we have no way of determining whether it is true or false (regardless of what anyone has ever told you). So, propositions are statements that something is the case that are either true or false, but we need not determine whether they are actually true or actually false for them to be propositions.

In academic logic, propositions are generally referred to using the symbolic shorthand P. This is the generic proposition, the Ur-proposition, in computer programming terms we might say it is the proposition type. Like algebraic variables, we can use any uppercase letter to designate other propositions. So, for example, if I needed to talk about three propositions, I could use P, Q, and R (these are the common letters used in academic circles, for whatever the reasons). Now, when dealing with multiple propositions there are two key operators that we will use3: & and v. Perhaps these symbols seem a bit foreign, but I promise that their concepts are utterly simple. & is the “and” operator; it combines two propositions to make one new proposition, called the “conjunction” of the two propositions. v is the “or” operator; it also combines two propositions to make one new proposition, called the “disjunction” of the two propositions. In high school English we would say that “and” and “or” are conjunctions, and just like in English class we can take two declarative sentences and combine them with a conjunction to make a new sentence. Ah, that sentence was a perfect example (almost as if I planned it ;)). So, symbolically we could write P & Q => R and P v Q => S.

Ok, so propositions can be combined to make new propositions in two different ways, but what precisely is the difference? Well, I’m interested in truth, so you might have already guessed the difference. The difference between R and S from above is what is required for them to be true. When using the & operator to combine P and Q, the conjunction R is only true when both P and Q are themselves true. If either P or Q is false, then R is also false. When using the v operator, the disjunction S is true if either P or Q is true. These relationships are most often considered using a “truth table”. Consider the following, which lays out all of the possible scenarios for the & operator:

P |

Q |

(P & Q) |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | F |

Here we can clearly see that the expression (P & Q) is only true whenever both the proposition P and the proposition Q are true. This is contrasted with the v operator:

P |

Q |

(P v Q) |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Here the relationship is almost the exact opposite. The expression (P v Q) is only false whenever both the proposition P and the proposition Q are false. In every other instance the expression (P v Q) is true, as one of the two constituent propositions is true.

These two operators handle how the truth values relate when combining two or more propositions, but there is one last operator we need to discuss, which is used on single propositions. The “negation” operator ¬ is used, you guessed it, to negate propositions. The truth table for this operator is pretty straight forward:

P |

¬P |

|---|---|

| T | F |

| F | T |

The negation operator basically just “flips” the truth value of the proposition.

With all of that now settled, we can finally turn to the heart of this excursion.

P & ¬P

#

Now, I will readily admit that “conjunctive binarism” is a phrase that I totally made up 4, but I was trying to find a phrase that accurately captured the idea I had in my head, which I was initially conceiving of in purely symbolic terms: P & ¬P 5. In many ways I find the symbolic phrase far clearer than the English phrase “conjunctive binarism”, but hopefully my English phrase at least accurately describes precisely what I’m interested in.

I said at the beginning that I was interested in the question “What is truth?”, yet now that we have a firmer grasp on what precisely “conjunctive binarism” means, I’m sure that you, my reader, are a bit worried. And, I would say, rightfully so. Here is the truth table for the conjunctive binary:

P |

¬P |

(P & ¬P) |

|---|---|---|

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

Well there you have it, the conjunctive binary (P & ¬P) can never be true 6. In many ways the the simplest, most intuitive answer to the question of “What is truth?” is “I don’t know, but it certainly isn’t (P & ¬P)”. In fact, Aristotle himself states this directly in his Metaphysics7:

The most certain of all basic principles is that contradictory propositions are not true simultaneously. (1011b13-14)

This idea, that a proposition (P) and its contradiction (¬P) cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time, is so fundamental to human logical thought that it is a law, the Law of Non-Contradiction.

Now, I am not quite so bold as to suggest that the Law of Non-Contradiction is wrong; however, I would like to press it a bit. The caveats in the definition of the LNC are clearly important. I’m sure we can all think of examples where a proposition (P) and its contradiction (¬P) are both true, just in different senses. As one contrived examples, the proposition “Citi is a bank” and its contradiction “Citi is not a bank” would both be true if “bank” in the first case meant “a financial institution” and “bank” in the second case meant “the side of a river”. Likewise, if time is not an issue, we can certainly conceive of an example where some proposition is true and then later its contradiction is true. Taking the same contrived example, right now the proposition “Citi is a bank” is true, but if in the future they were to go out of business, the contradiction “Citi is not a bank” would then be true.

What I would like to suggest is that while the Law of Non-Contradiction is strictly true, it is not practically all that helpful when confronting the question “What is truth?”. Specifically, I would argue (and hopefully I will at some point soon) that in the everyday world one of those two caveats is very likely to be true. That is to say, I contend and my definition of Conjunctive Binarism states that a proposition (P) and its contradiction (¬P) are likely both true either in different senses or at different times. More simply, I argue that (P & ¬P) will likely be true in some way.

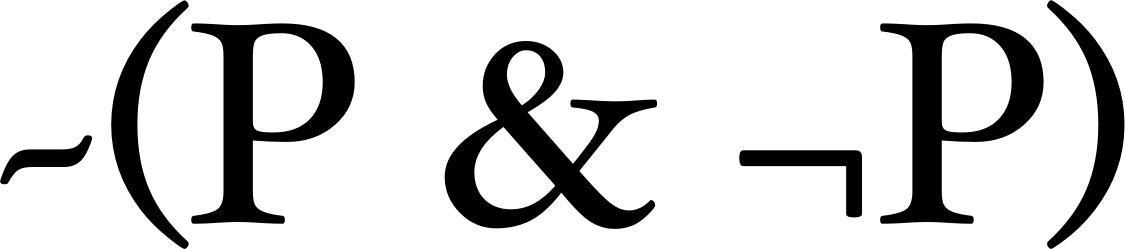

If I could create my own logical symbol, I would create the “fuzzy” symbol ~, which would denote the existence of one or more of these caveats. In my logical lexicon the “fuzzy” symbol ~ generally maps to the English word “kinda”. So, in strictest form Conjunctive Binarism would be expressed symbolically as ~(P & ¬P), or even more strictly as (~P ~& ~¬P). In plain English we might say “the proposition P and its contradiction ¬P are kinda both true”.

Fin #

I plan, in later posts, to explore this thesis from various angles, to consider some of its consequences, and to argue for its correctness. For now, however, I leave it at this: my answer to the question “What is truth?” would be, in a more rigorous and philosophic way than this sounds, “Kinda everything”.

-

The term “alethiology” is fairly rare in academia; for example, the ten-volume Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy mentions it only once. ↩

-

For those readers of a more academic bent, this article from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provides a robust explanation of this analysis of knowledge, and indeed of knowledge in general. ↩

-

There are, in fact, many other logical operators beside these two:

Sign Operator &“and” v“or” →“if… then…” ↔“if and only if” ¬“not” -

A Google search for the exact phrase “conjunctive binarism” returns no results. ↩

-

This construction of the constructive binarism marks it as a close kin of dialetheism, a newer philosophical position that holds that dialetheias do in fact exist, and a dialetheia is simply a sentence,

A, such that both it and its negation,¬A, are true; that is,A & ¬A. ↩ -

This is in direct contrast with the disjunctive binary, which is always true.

P¬P(P v ¬P)T F T F T T In fact, the disjunctive binary, by definition, includes all possible states, as any state would either be

Por¬P. Since¬Pis simply the negation ofP, the disjunction offers a logically exhaustive set of states. ↩ -

This article from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provides a rich analysis of Aristotle on the Law of Non-Contradiction. ↩