I have entitled this website “Fractaled Mind”, and in this inaugural post I want to begin to explain why. What ought the mind to do with fractals? What are fractals? And what the hell do they have to do with ducks and rabbits? Hopefully, I can answer this and a few other questions as well.

To begin, let’s consider precisely what a fractal is. This website’s logo incorporates the infinitely intriguing Dragon Curve fractal. This particular fractal is generated by a relatively simple recursive procedure: Imagine a right angle isosceles triangle without its hypotenuse (thus two line segments connected by a 90 degree angle); replace each line segment with another 90 degree angle (so image drawing another isosceles triangle where one of the original line segments is the hypotenuse, and then removed); each subsequent replacement 90 degree angle alternates is orientation. Now, this is clearly somewhat difficult to describe, but (as they say) a picture is worth 1,000 words:

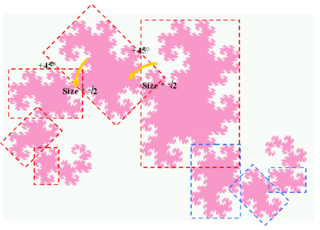

Why spend our time on these details? Well, because they help to illustrate the central defining characteristic of fractals – they are self-similar. As the mathematician Kenneth Falconer puts it: a fractal “contains copies of itself at many different scales.” This essential property can be seen quite clearly in a more fully articulated Dragon Curve:

Here, the same pattern is repeated as it tilts 45 degrees and is shrunk down (by a factor of √2, FWIW).

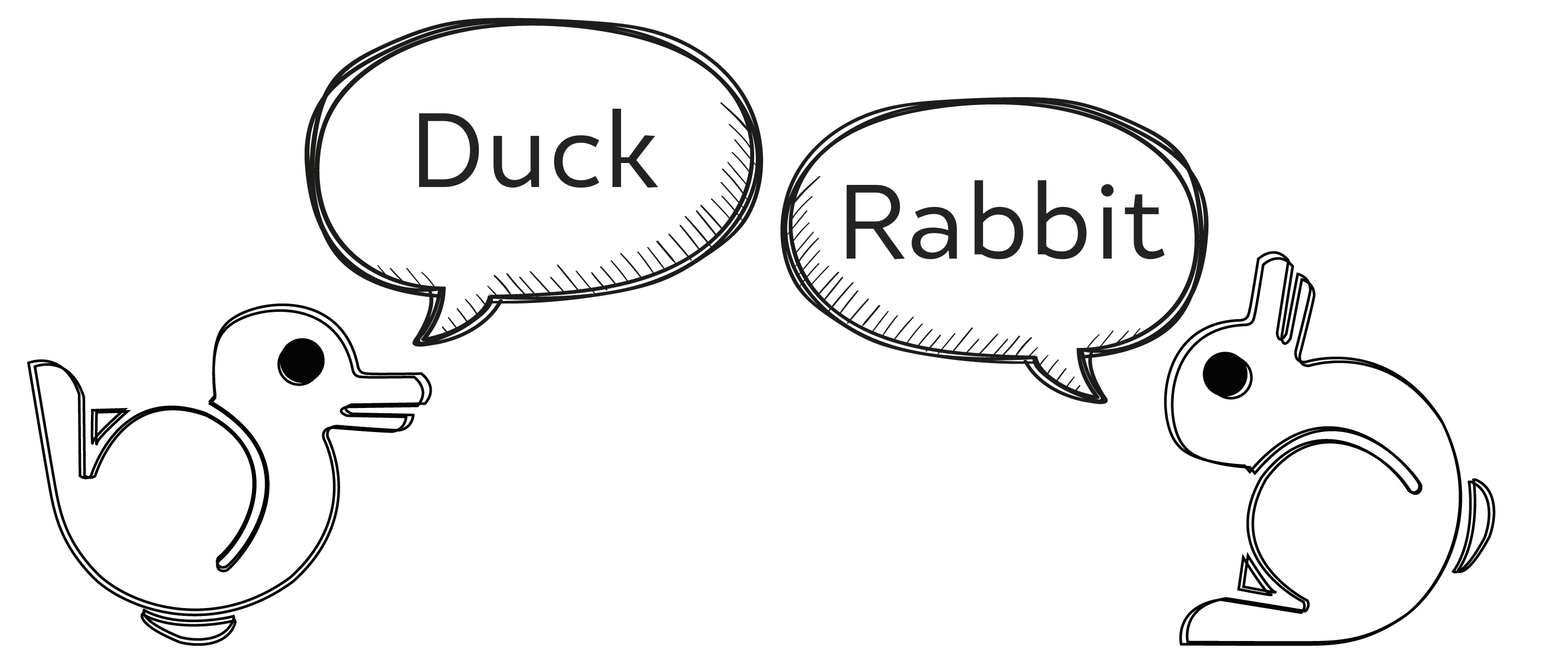

In fractals, this self-similarity is shifted along the scale spectrum. You can zoom in or zoom out to find “copies”. Often, along with scale, the self-similarity is also shifted via rotation, as with the dragon curve fractal above. The duck-rabbit optical illusion traces its origins back to 1892 in a German magazine, and has been fascinating observers ever since.

Here we observe a different kind of “self-similarity”. This image contains two “copies of itself”, but at the same scale and same rotation. Indeed, there is only one image. And yet, our perception can flick between two distinct “copies” – the duck and the rabbit.

This “duck/rabbit” phenomenon can be seen in another instance where rotation does play a role:

Here the same image can present two distinct impressions, based on its rotation alone. Ok, but what of it?

Fractals and optical illusions provide concrete, visual examples of paradoxes, and paradoxes are truly one of my deepest fascinations. For a fractal with scaled self-similarity, a section of the fractal is both part and whole, depending on scale. It is itself a part of a larger whole, and yet also contains that full whole within itself. This can be captured with the trippy GIFs seemingly infinitely zooming in on a fractal.

Likewise, the duck/rabbit illusion with rotational self-similarity provides an image that is both duck and rabbit, depending on rotation. And, of course, this is most starkly the case with the original duck/rabbit image, which has pure self-similarity. It is both duck and rabbit, depending only on how your brain wants to perceive it in that moment.

These are paradoxes because in the “real world”, objects cannot behave like this. A duck is a duck, and it can never also be a rabbit. A part is a part, and can never also contain its whole. And yet, these paradoxical objects exist. This picture exists, and it is only 1 picture, and yet it encodes two distinct pictures. And fractals exist, and they are parts that contain wholes.

I want to develop a mind that sees fractals. I want to think that parts can contain wholes or a duck can be a rabbit. Not in some fantastical, unhinged from reality way, but simply in the way to respects the existence of these paradoxes, and others like them. And I see my own mind in that way, a fractal where the parts contain the whole, where I zoom in and in only to seemingly find myself back where I started, where I look at something and see two somethings. My mind is fractaled. And so is yours. How fascinating.